“Celebrate what every decade gives to you, not what it takes away.”

On September 2, Marge Champion, the legendary and beloved dancer/ choreographer, begins a new decade in her life — this time as a centenarian.

The advice quoted above, which she often dispensed to me and other friends through the years, will undoubtedly hold firm as she enters a new life journey. Marge will also, I feel sure, be accompanied by her enormous reserves of positive energy, kindness, down-to-earth practicality, and, most important, a great sense of humor about herself and life in general.

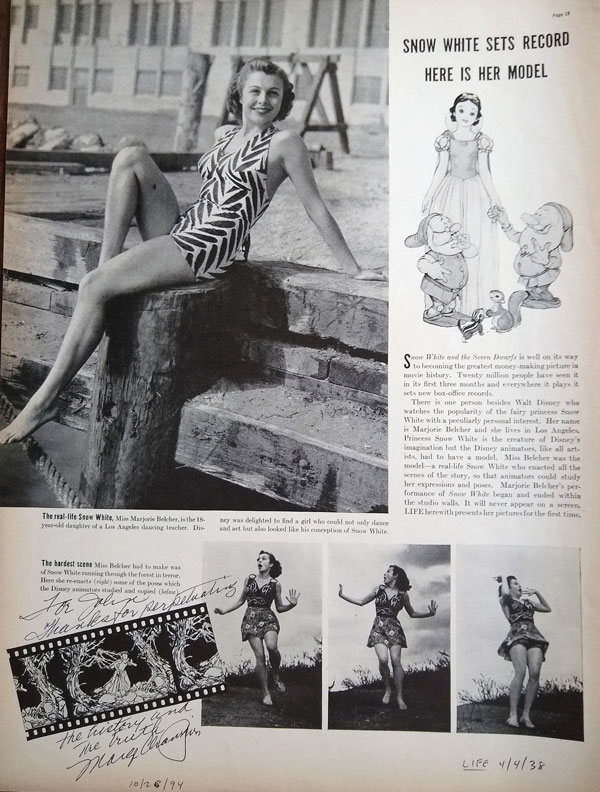

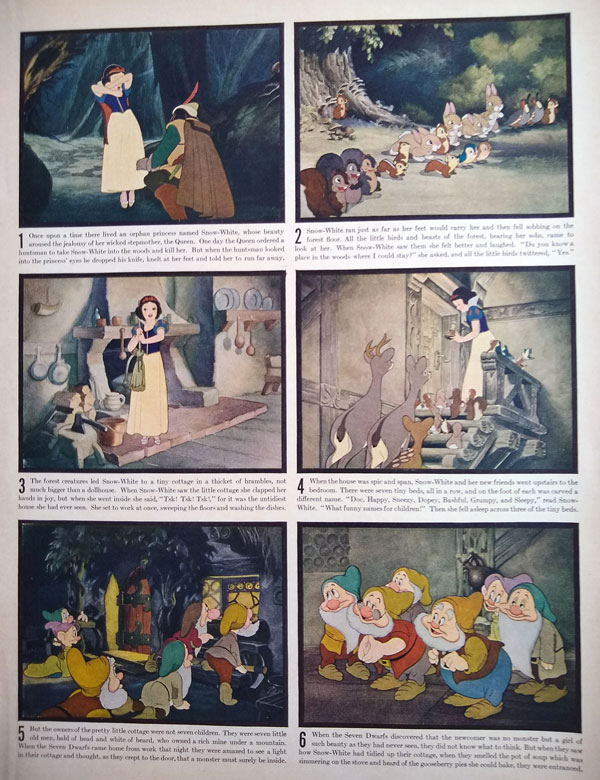

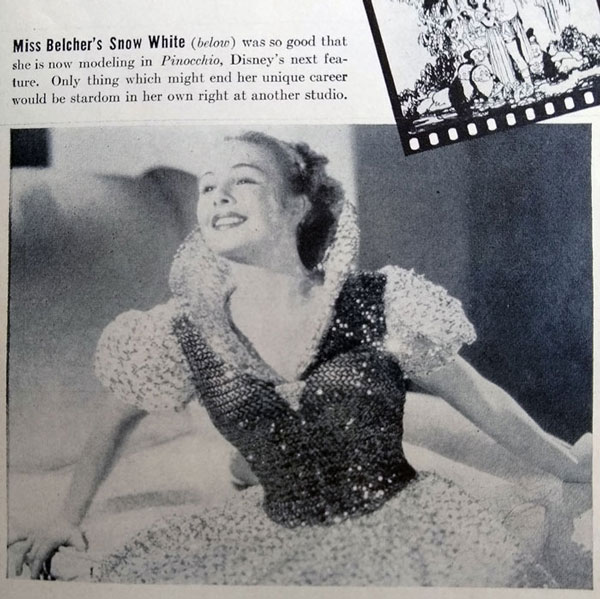

She was born Marjorie Belcher in 1919, the daughter of Hollywood dance instructor Ernest Belcher. Her earliest experience in film was in the mid-1930s when she was a teenager. As many of her fans know, she was the live-action reference model for the princess Snow White in Walt Disney’s first feature-length cartoon, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, released in 1937.

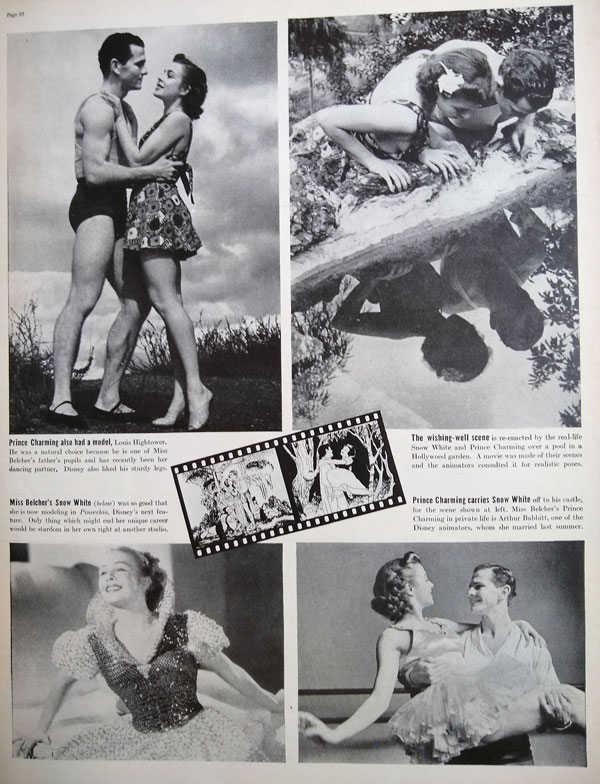

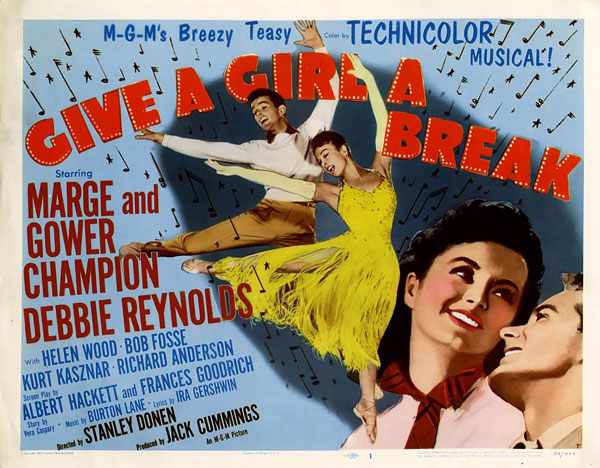

Eventually, Marge gained international fame performing with her husband, the dancer/choreographer Gower Champion (1919-1980), in a dazzling series of MGM musical films. Their featured roles in Show Boat (1951), Lovely to Look At (1952), Give a Girl a Break (1953), among other films, led to lucrative engagements at top nightclubs and early television variety show appearances. They even had their own TV series in 1957.

Marge and Gower Champion’s performances, both on screen and in person, endeared them to audiences around the world. Critic John Crosby described them as, “Light as bubbles, wildly imaginative in choreography, and infinitely meticulous in execution. Above all, they are exuberantly young.”

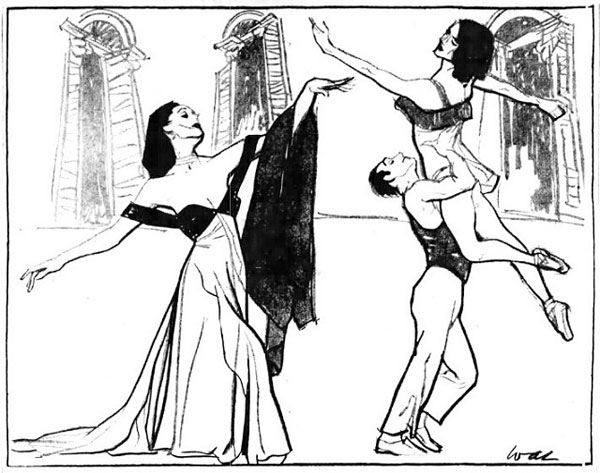

One of my favorites of the couple’s screen performances is a surreal faux-ballet in the live-action 1955 musical, Three for the Show (1955).

To the classical strains of Swan Lake, Jack Cole’s sardonic choreography presents a most un-Snow White-like Marge as a distraught, jealous, elegantly gowned murderess (the number runs from 37:53 to 44:26). Both Gower and Marge are wonderful in the over-the-top piece; but Marge displays a wide range in this parody of Hollywood musical numbers: she’s sexy, athletic, funny and technically perfect.

On her own, Marge created dances for films (The Day of the Locusts), theatre (Stepping Out; Grover’s Corners) and television; her choreography for the TV special Queen of the Stardust Ballroom won her a 1975 Emmy.

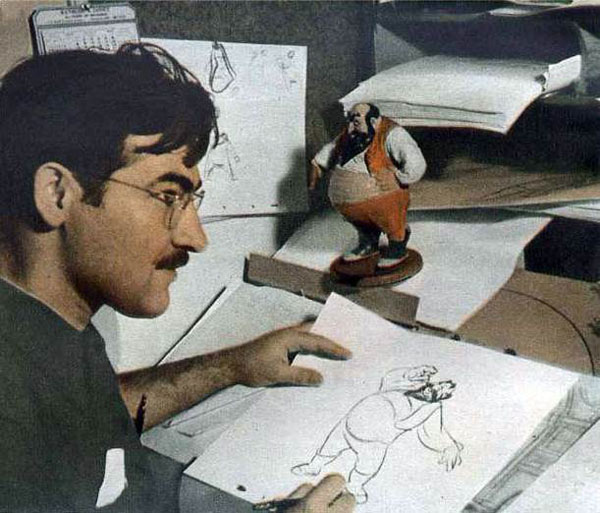

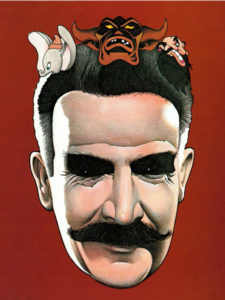

I was introduced to Marge Champion on May 5, 1981 by Art Babbitt (1907-1992) at his wife Barbara Perry’s opening of her one-woman show, Passionate Ladies, on Broadway. Art, a great Disney animator, met Marge during Snow White’s production and became her first husband, briefly. “Our marriage bumped into a career,” he once said of Marge’s desire to excel as a performer. He wanted a housewife, instead of a shooting star.

Some years later, Art married Barbara Perry (1921-2019), a gifted dancer and actress, who often performed with the Champion’s in films, nightclubs and television projects. They were all show biz friends. Laughing, Marge once recalled to me the day Barbara phoned her out of the blue to say:

“You’ll never guess what I’ve gone and done.”

“What?” said Marge.

“I’ve married your old husband!”

Through the years, Marge shared with me many anecdotes about her life and career, privately, but often publicly in interviews on film and stage. She was candid in discussing the tragic death of her third husband, director Boris Sagal (1923-1981). She held on to long friendships with artists she met at Disney, such as master animator Vladimir Tytla and his wife Adrienne; and for years she sent money to help sustain the designer Ferdinand Horvath and his wife Elly.

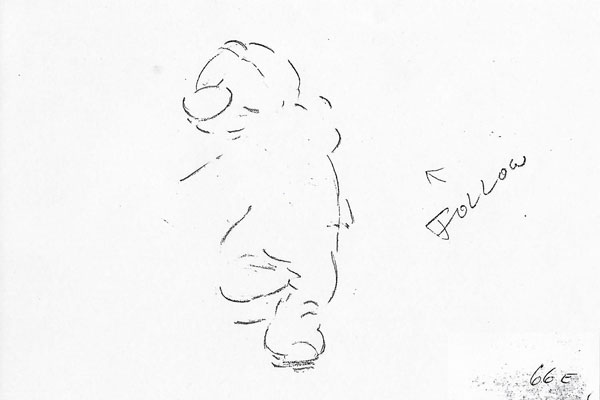

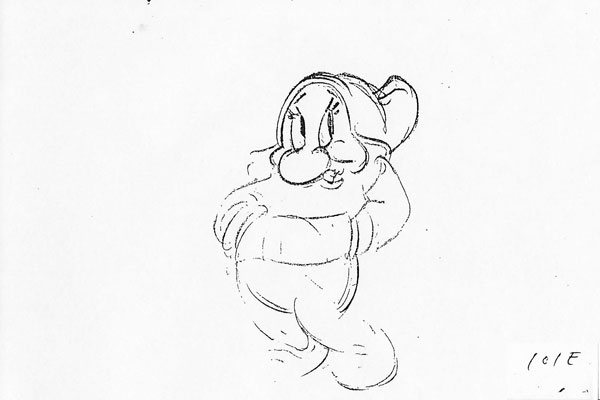

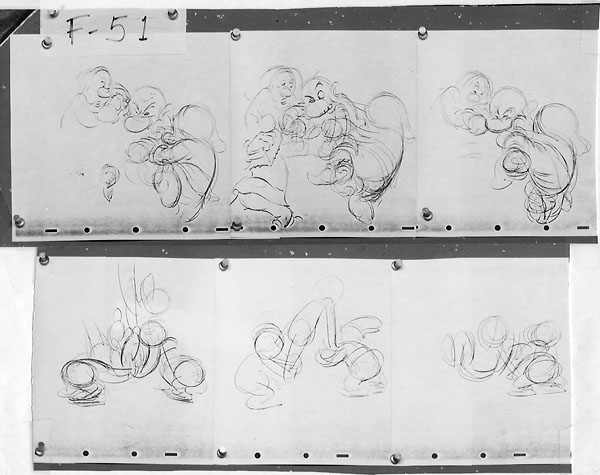

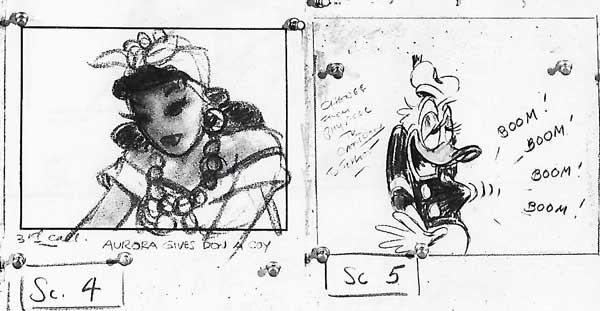

Her memories of her varied and fascinating career were always sharp and accurate, including her earliest experiences at Disney. She recalled, for example, the small, unadorned stage at the Disney Studio, where for two or three days a month for a couple of years, teenaged Margorie Belcher improvised mime/dance movements that were shot on film. Wearing a long skirt, she moved, danced and emoted as Snow White, sometimes dancing with “gooney, really tall” musicians and animators pretending to be dwarfs.

“The animation supervisor [Ham Luske] would show me the storyboards,” she explained, “a crude set, props, and they had the [soundtrack] playback . . . It was like Mickey [Rooney] and Judy [Garland’s musical films] — let’s put on a show! They’d show me this stuff and turn me loose and I’d do it.”

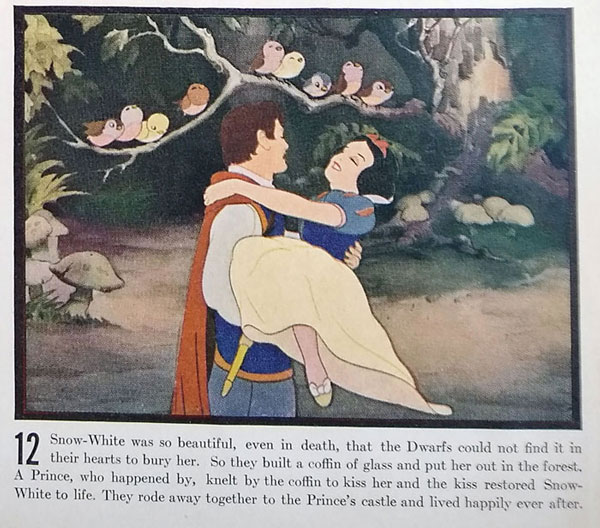

The animators and Walt studied the films, noting the timing of Marge’s actions, studying her pose-to-pose movements, the way her dress and hair moved in every scene.

Preferred takes of Marge’s image were traced frame-by-frame (“rotoscoped”) as a guide to aid the animators in transferring her image to their drawing boards and ultimately the silver screen. For example, the sequence where Snow White runs through a dark forest of grasping tree branches and clinging vines. To aid the animators, Marge acted frightened and improvised a run through a forest mock-up — a clothesline hung with dangling ropes, which she pushed aside while running.

“When I finally saw the finished product,” she says, “I realized that every single movement was mine.” Her pay was “the magnificent sum of $10 a day.”

But she enjoyed the experience, comparing the studio to a high school or college campus. On camera Marjorie Belcher often mimed to the singing of Adriana Caselotti, who provided the princess’ unusual voice. One animator couldn’t resist jumbling and recombining their names into a playful burp: “Margiana Belchalotti.”

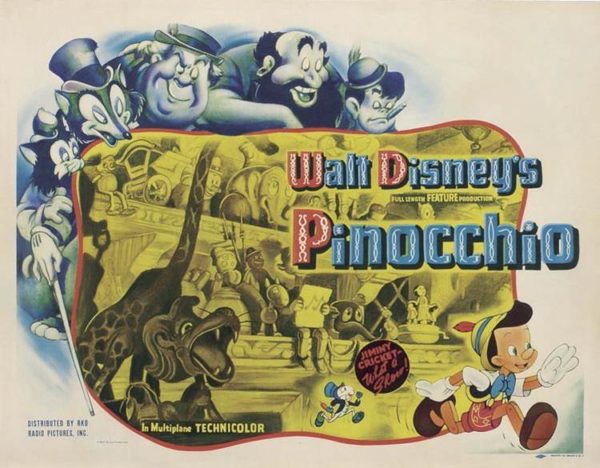

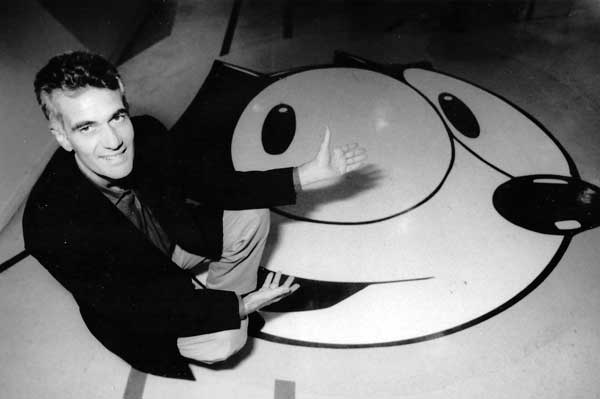

Disney and his team were so pleased with Marjorie’s performance, they next hired her as the reference model for the ethereal Blue Fairy in Pinocchio (1940). For Fantasia (1940), she became the stand-in for a huge, but dainty, tutu-clad hippo ballerina. She also directed eleven young women, from her father’s dancing school, as a chorus of Sally Rand fan-wielding ostriches and bubble-dancing pachyderms. “We did stuff with balloons,” she said.

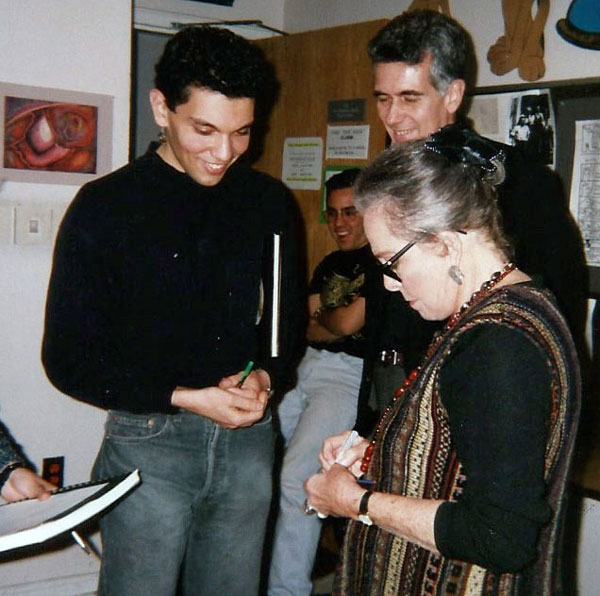

A certain memory of Marge stands out to me: it happened at the 2007 Platform International Animation Festival, one of the best American animation festivals ever, thanks to Irene Kotlarz, the imaginative organizer. She invited me to interview Marge Champion on stage after a screening of a restored print of Snow White, honoring the film’s 70th anniversary.

Early in the day, Marge, a thorough professional, insisted that we check out the theatre and stage where we would converse that evening. “I never step foot on a stage I don’t know,” she explained.

That night, we sat together in the audience, Marge watching the movie she’d made over seven decades ago; me watching and listening to her delighted reactions and whispered comments. It was a lovely, strange feeling to sit next to Snow White, as she watched herself on the screen.

On screen, as Snow White was awakening from the Prince’s kiss, an usher summoned us backstage to prepare for our on-stage conversation. In the dark, separated by a giant screen on which animated cartoon characters played their final scenes, with music swelling loudly on the soundtrack, Marge bid me goodbye as she was guided by flashlight across the stage, behind the giant movie screen. She would make her entrance after my introduction from the opposite side of the stage, as rehearsed.

While waiting for the film to end, I had the privilege to experience a wonderful, time-tripping sight. On the huge movie screen, a gigantic Princess kissed gigantic dwarfs goodbye, and a gigantic Prince carried her to his horse,rode into a shimmering sunset toward a castle emerging from mist, while a chorus with full orchestra sang “Someday My Prince Will Come.” I could see all that on the huge screen. Then, stepping to the left I saw Marge, age 88, way across the stage exercising, stretching, getting herself ready to meet another audience, as she did at Disney’s little sound stage, or New York’s posh Persian Room at the Plaza Hotel, or the London Palladium, as she did before facing MGM’s Technicolor cameras, or audiences in Leningrad and Moscow.

Step to the right – there she was again as Snow White.

Step to the left: a little lady, a true professional, preparing herself to meet the public, to give the folks a great show.

And she did.

Views: 6418

On Thursday, October 18, I will be speaking at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, about one of Walt Disney’s most remarkable animated features, Pinocchio (1940).

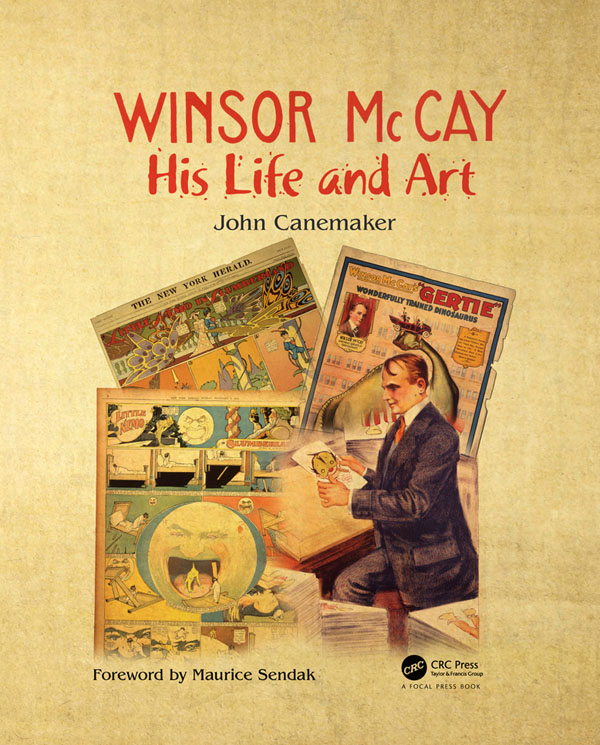

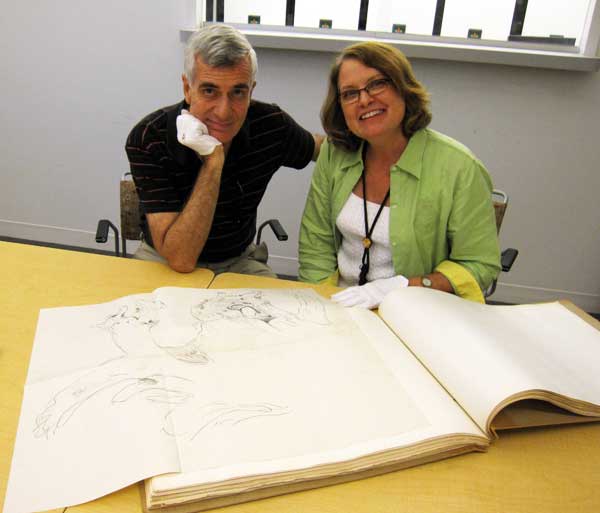

On Thursday, October 18, I will be speaking at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, about one of Walt Disney’s most remarkable animated features, Pinocchio (1940). I am pleased and proud to announce that my 1987 biography of Winsor McCay will be published this week in a beautiful Revised Edition by CRC Press.

I am pleased and proud to announce that my 1987 biography of Winsor McCay will be published this week in a beautiful Revised Edition by CRC Press.

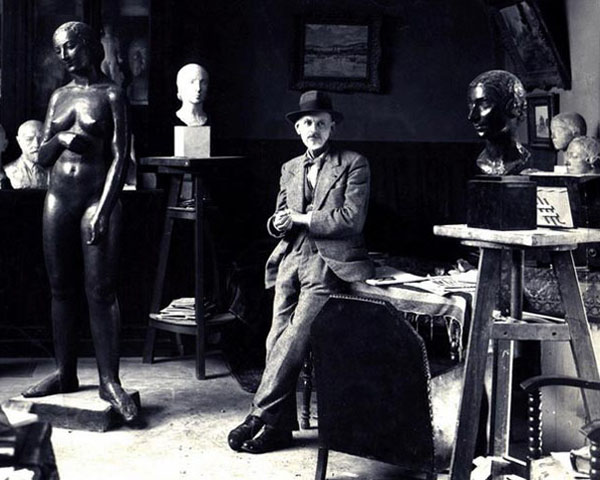

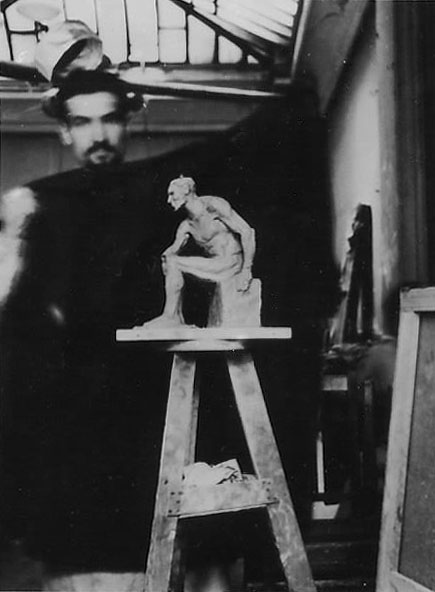

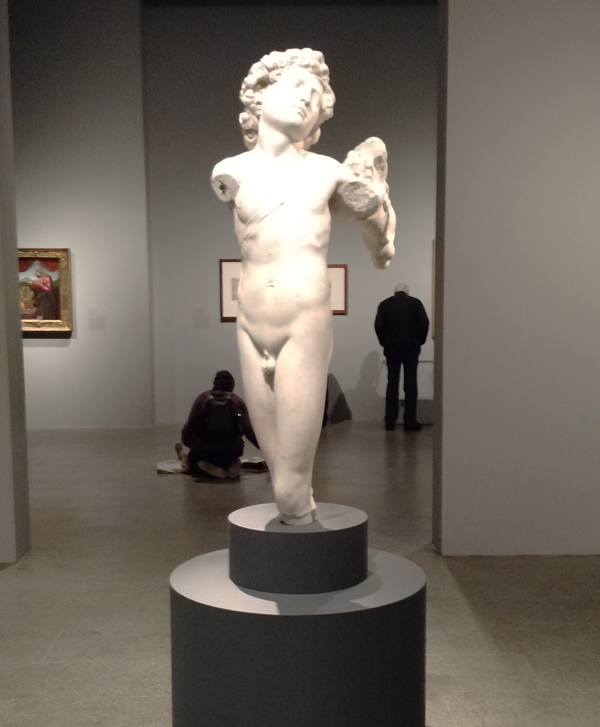

Suddenly, a nude man, armless — and headless — strode by.

Suddenly, a nude man, armless — and headless — strode by. It was Auguste Rodin’s magnificent “Walking Man.” Despite lacking a few body parts, the statue breathed life; strong and confident, he swung into a gait with a contrapposto hip twist.

It was Auguste Rodin’s magnificent “Walking Man.” Despite lacking a few body parts, the statue breathed life; strong and confident, he swung into a gait with a contrapposto hip twist.

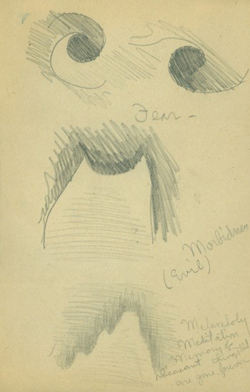

Tytla’s description (to animation historian

Tytla’s description (to animation historian

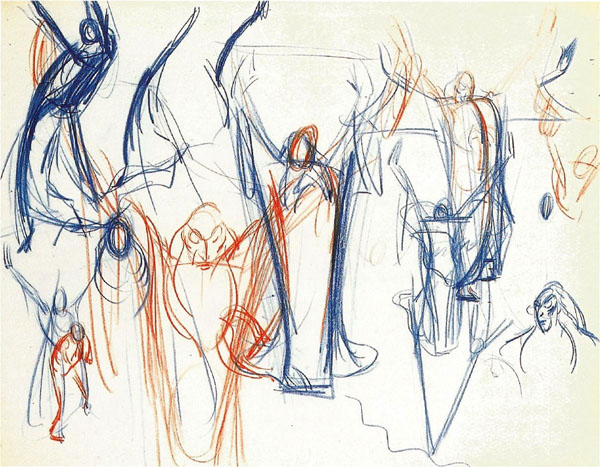

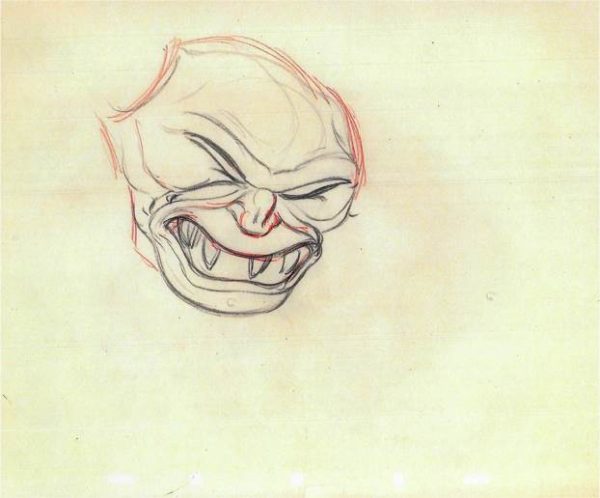

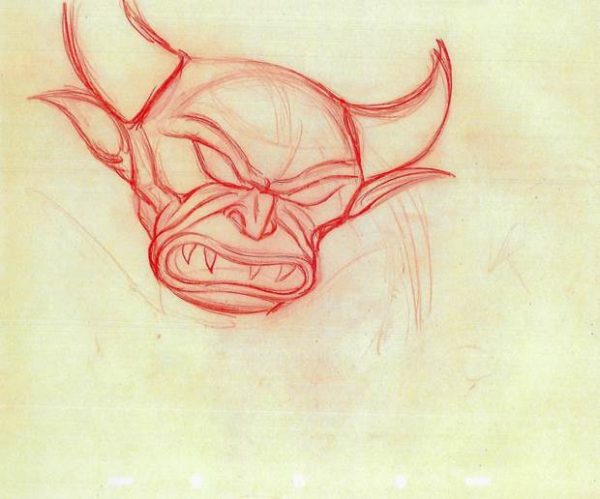

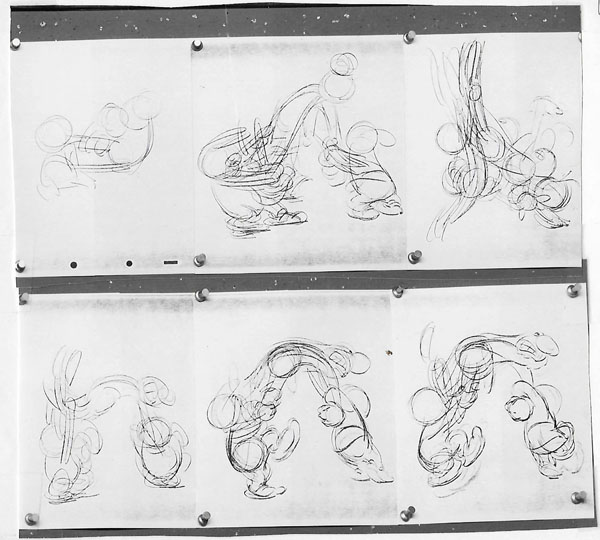

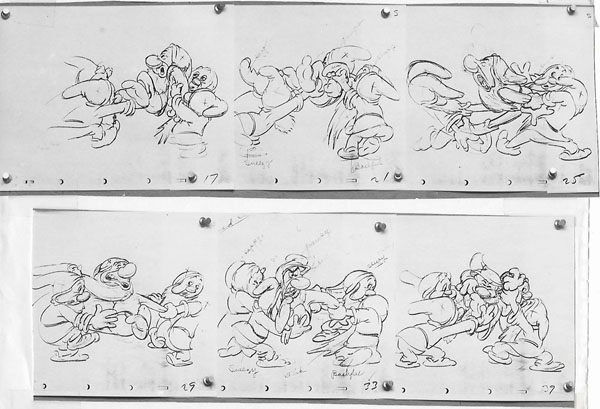

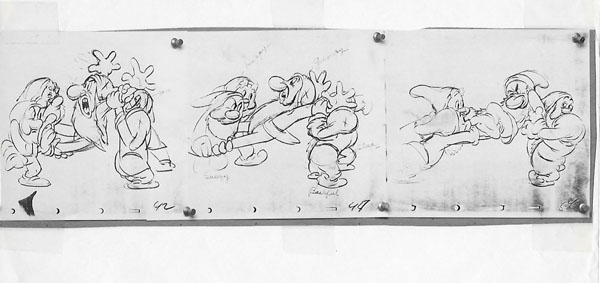

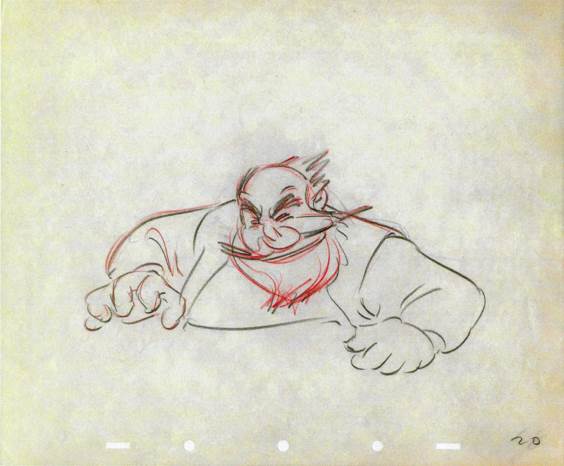

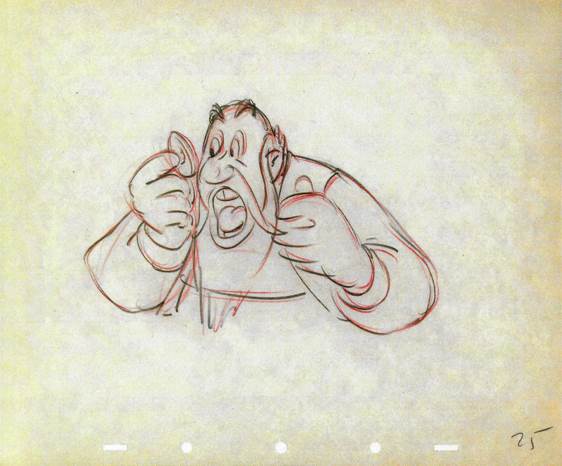

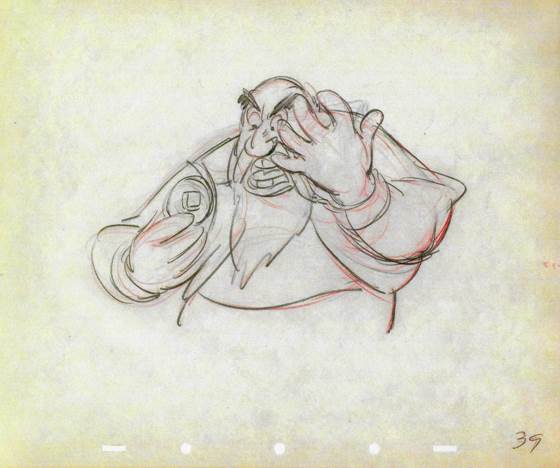

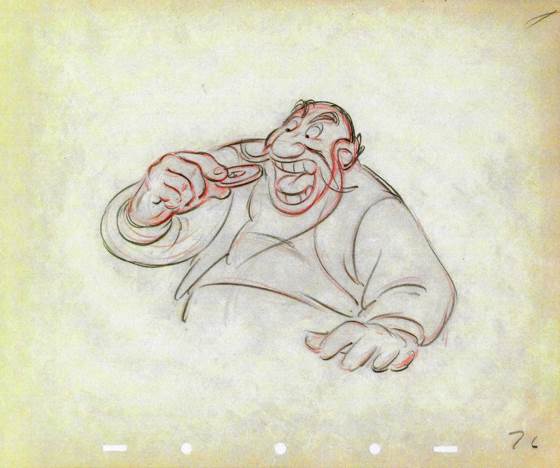

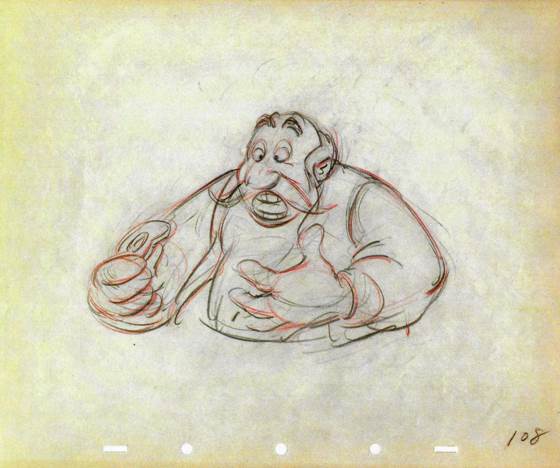

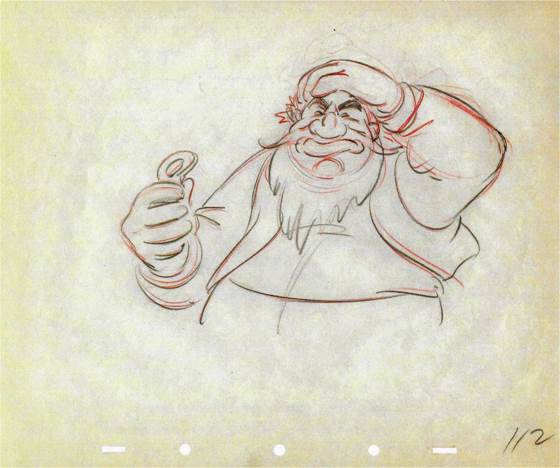

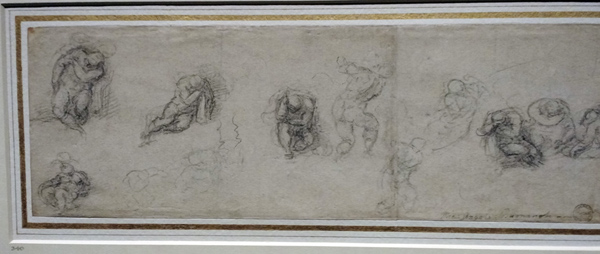

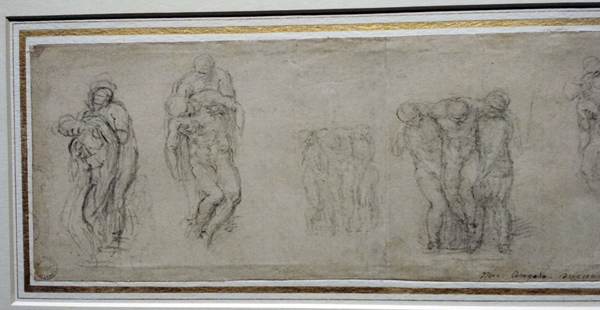

So, too, are a selection of rough scribbles and a second pass of more refined lines and details clarifying a scene in which Grumpy is violently carried to a bathtub. The vitality of the actions depicted is palpable even in still drawings. On the screen, it explodes.

So, too, are a selection of rough scribbles and a second pass of more refined lines and details clarifying a scene in which Grumpy is violently carried to a bathtub. The vitality of the actions depicted is palpable even in still drawings. On the screen, it explodes.

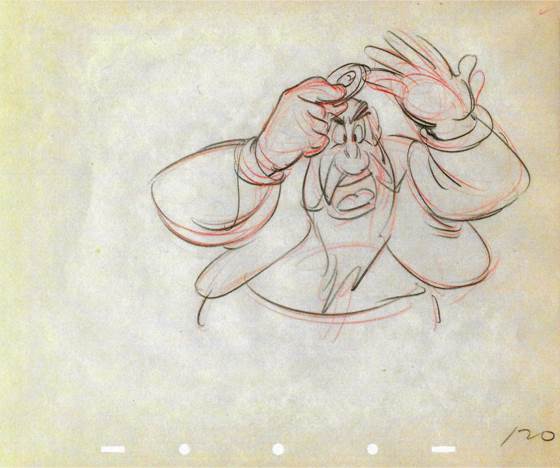

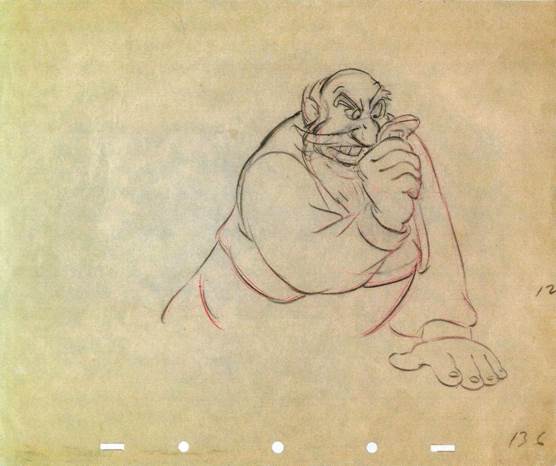

Tytla also looks for, and usually finds, ways that give his character someplace to go. Moving Stromboli from one side of the screen to the other in most scenes adds visual variety and texture to the moving composition. His work is not static; it is progressive.

Tytla also looks for, and usually finds, ways that give his character someplace to go. Moving Stromboli from one side of the screen to the other in most scenes adds visual variety and texture to the moving composition. His work is not static; it is progressive.

Frederic Franklin, the great, high-spirited, charismatic, British-born dancer and ballet master, performed from his teens into his 90s, and inspired numerous choreographers to create for him, including Léonide Massine of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, George Balanchine (Danses Concertantes) and Agnes de Mille (Rodeo).

Frederic Franklin, the great, high-spirited, charismatic, British-born dancer and ballet master, performed from his teens into his 90s, and inspired numerous choreographers to create for him, including Léonide Massine of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, George Balanchine (Danses Concertantes) and Agnes de Mille (Rodeo).

Soon after, on June 4, 2012, Mindy, a friend of Freddie’s for many years, arranged for us both to chat with him at his penthouse apartment on West End Avenue on New York’s Upper West Side, where he and his partner, William Haywood Ausman, lived for 45 years.

Soon after, on June 4, 2012, Mindy, a friend of Freddie’s for many years, arranged for us both to chat with him at his penthouse apartment on West End Avenue on New York’s Upper West Side, where he and his partner, William Haywood Ausman, lived for 45 years. He was 98 years old at the time, but full of energy, warmth and charm. I was in awe of his ability to answer, with sharp recall, inquiries about his fabled career. During a second visit, on August 16, I wisely brought a tape recorder, with Freddie’s permission. For each time, he took us on a personal journey through nearly a century in the dance arts.

He was 98 years old at the time, but full of energy, warmth and charm. I was in awe of his ability to answer, with sharp recall, inquiries about his fabled career. During a second visit, on August 16, I wisely brought a tape recorder, with Freddie’s permission. For each time, he took us on a personal journey through nearly a century in the dance arts. Dressed in a white cable-knit sweater and slacks, Freddie sat ramrod-straight looking like a grand egret, his long arms and hands making expressive movements abetted by spot-on vocal mimicry. Through his verbal and mimetic gestures, I saw him dancing at age six at his home in Liverpool, listening to a gramophone and jumping around in front of a mirror after seeing a production of Peter Pan.

Dressed in a white cable-knit sweater and slacks, Freddie sat ramrod-straight looking like a grand egret, his long arms and hands making expressive movements abetted by spot-on vocal mimicry. Through his verbal and mimetic gestures, I saw him dancing at age six at his home in Liverpool, listening to a gramophone and jumping around in front of a mirror after seeing a production of Peter Pan. His first teacher, Marjorie Kelly, ran a local classical ballet school. “Oh god, she was a tough lady, but a very good teacher,” he recalled. “I was terrified of her.” At their first meeting, she commanded, “Young man, do something!” So the tot got up and . . . jumped around. After a brief discussion with his mother, the prescient Mrs. Kelly announced, “I’ll take him. He’s good!”

His first teacher, Marjorie Kelly, ran a local classical ballet school. “Oh god, she was a tough lady, but a very good teacher,” he recalled. “I was terrified of her.” At their first meeting, she commanded, “Young man, do something!” So the tot got up and . . . jumped around. After a brief discussion with his mother, the prescient Mrs. Kelly announced, “I’ll take him. He’s good!”

See the video trailer

See the video trailer

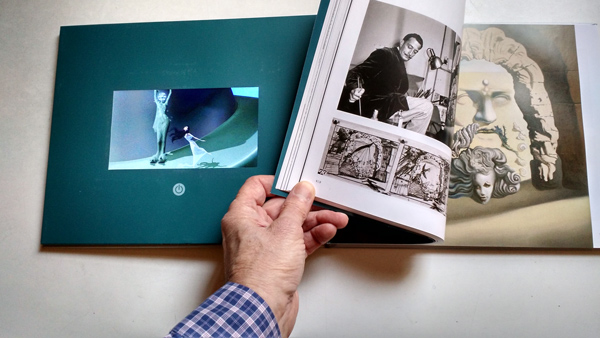

Over the Christmas holiday, author David A. Bossert dropped by New York City with a “special limited edition” of his informative book about Destino, the unusual film collaboration between Walt Disney and Salvador Dali, and their subsequent Odd Couple friendship.

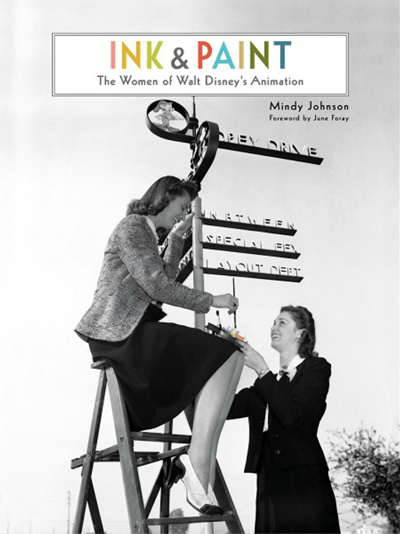

Over the Christmas holiday, author David A. Bossert dropped by New York City with a “special limited edition” of his informative book about Destino, the unusual film collaboration between Walt Disney and Salvador Dali, and their subsequent Odd Couple friendship. This large format book truly catches the zeitgeist of today’s progressive Women’s Movement. Historian Mindy Johnson’s scholarly, entertaining, profusely illustrated tome focuses on the important contributions made by women at the Walt Disney Studio.

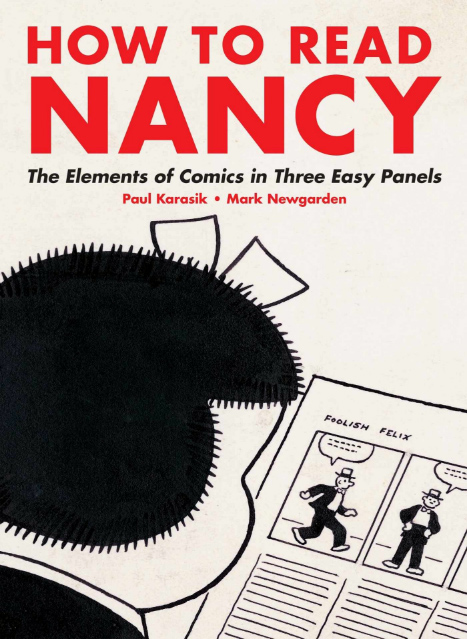

This large format book truly catches the zeitgeist of today’s progressive Women’s Movement. Historian Mindy Johnson’s scholarly, entertaining, profusely illustrated tome focuses on the important contributions made by women at the Walt Disney Studio. When I was a kid in the 1950s, I loved Harvey Kurtzman and his Mad magazine cohorts: cartoonists who drew wild, satiric action panels lobbing parodic grenades of ridicule at Eisenhower-era complacency and conformity. I thought, by contrast, Ernie Bushmiller’s comic strip Nancy was so . . . booorrring. I disliked the minimal, bland design, the lame jokes, the going-nowhere lead characters: chubby Nancy with her porcupine-hair and concrete hair bow, and her chubby pal Sluggo wearing his eternally stupid hat.

When I was a kid in the 1950s, I loved Harvey Kurtzman and his Mad magazine cohorts: cartoonists who drew wild, satiric action panels lobbing parodic grenades of ridicule at Eisenhower-era complacency and conformity. I thought, by contrast, Ernie Bushmiller’s comic strip Nancy was so . . . booorrring. I disliked the minimal, bland design, the lame jokes, the going-nowhere lead characters: chubby Nancy with her porcupine-hair and concrete hair bow, and her chubby pal Sluggo wearing his eternally stupid hat. It’s all true and it’s all there: how to stage a gag for maximum impact; how to draw strong storytelling poses; how to write succinct dialogue; what to leave in and leave out of a drawing; the staging of action; Bushmiller’s place in the history of comic strips. Their fascinating book is a clarion call for clarity in art — the foundation without which, as Stephen Sondheim says, “nothing else matters.” Cartoonists: buy this book, read it, and live it!

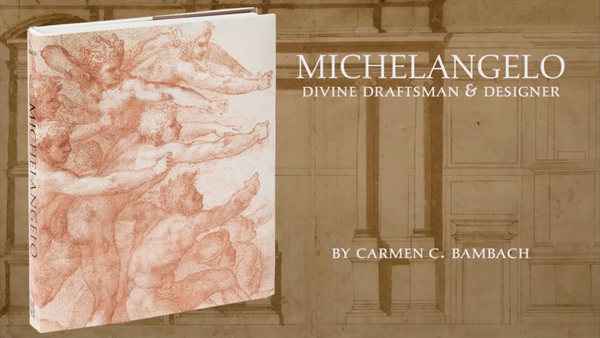

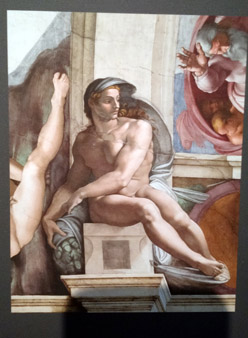

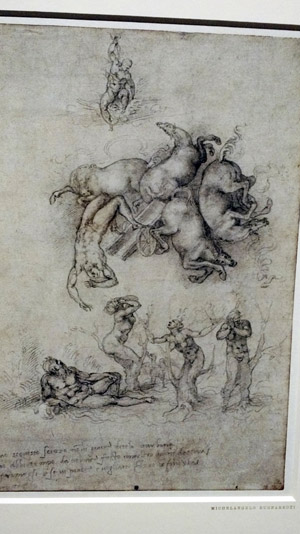

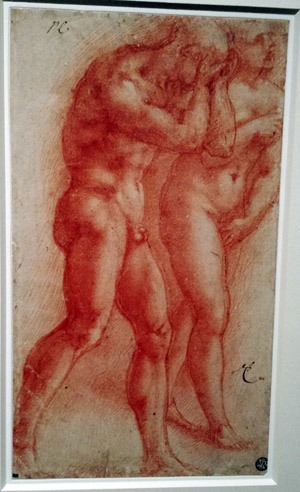

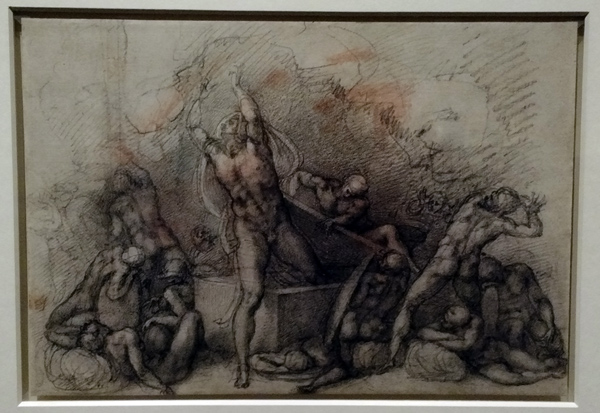

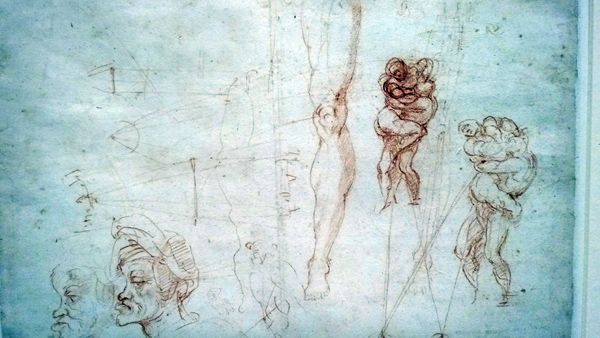

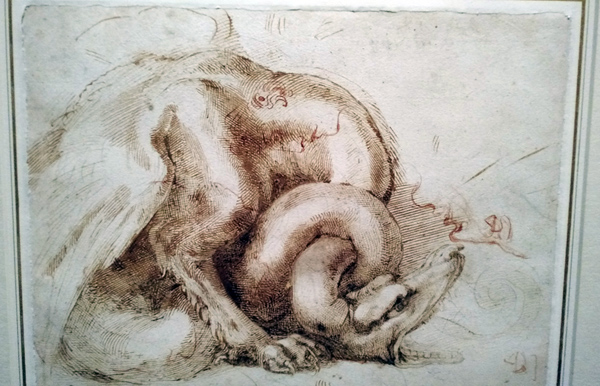

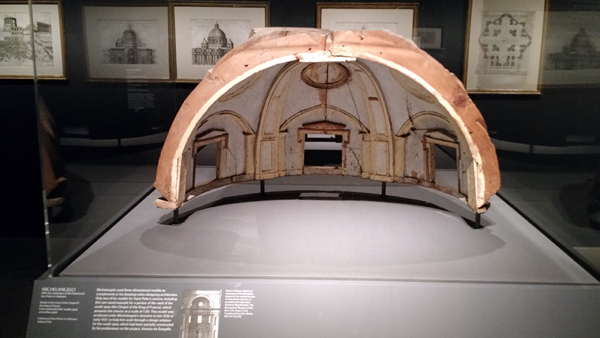

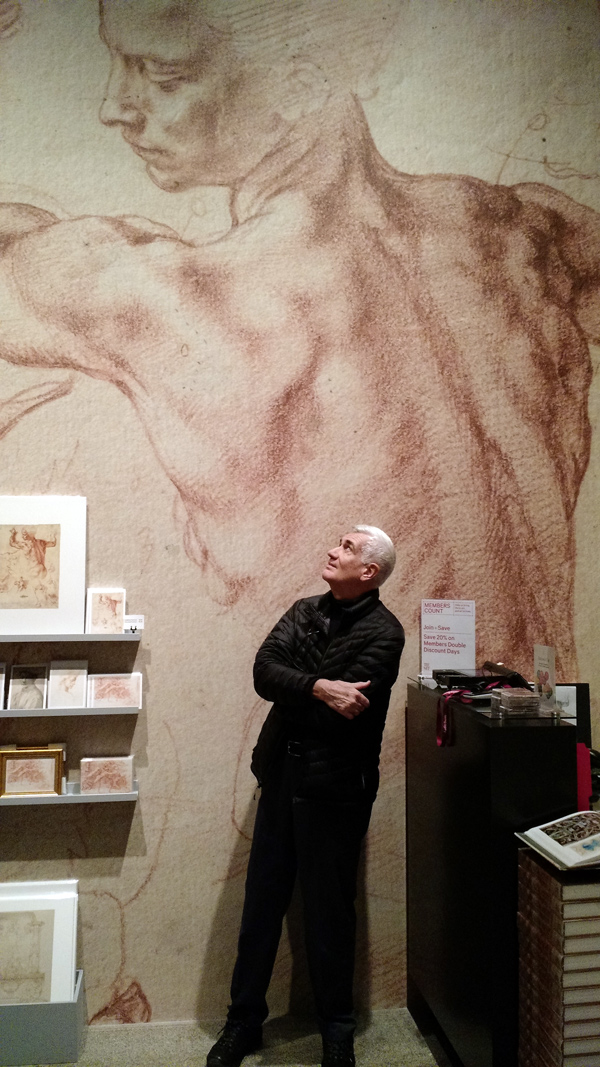

It’s all true and it’s all there: how to stage a gag for maximum impact; how to draw strong storytelling poses; how to write succinct dialogue; what to leave in and leave out of a drawing; the staging of action; Bushmiller’s place in the history of comic strips. Their fascinating book is a clarion call for clarity in art — the foundation without which, as Stephen Sondheim says, “nothing else matters.” Cartoonists: buy this book, read it, and live it! Fret not if you missed visiting in person the recent grand, magnificent exhibition of Michelangelo’s drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This large book has illustrations of all the art displayed in the show, accompanied by cogent essays written by the show’s curator (Ms. Bambach) and five other Michelangelo experts.

Fret not if you missed visiting in person the recent grand, magnificent exhibition of Michelangelo’s drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This large book has illustrations of all the art displayed in the show, accompanied by cogent essays written by the show’s curator (Ms. Bambach) and five other Michelangelo experts. Apologies, dear Readers, for the delay in posting on the Animated Eye. It was a busy holiday season, part of it spent traveling, a highlight of which was an all-too-brief visit to Havana, documented below in text and photos by me and Joe Kennedy.

Apologies, dear Readers, for the delay in posting on the Animated Eye. It was a busy holiday season, part of it spent traveling, a highlight of which was an all-too-brief visit to Havana, documented below in text and photos by me and Joe Kennedy.

Following are some images and thoughts from our visit. Though brief, it allowed a tantalizing glimpse of the island’s cultural heritage in art exhibitions, architecture, music, and dance, and it left us hungry to return for more.

Following are some images and thoughts from our visit. Though brief, it allowed a tantalizing glimpse of the island’s cultural heritage in art exhibitions, architecture, music, and dance, and it left us hungry to return for more.

The wide Plaza de San Francisco de Assis features baroques structures, including the old customs house and the Basilica, built in the late 1500s, with its high bell tower dominating the space with imposing grandeur.

The wide Plaza de San Francisco de Assis features baroques structures, including the old customs house and the Basilica, built in the late 1500s, with its high bell tower dominating the space with imposing grandeur. The Plaza de la Catedral’s eponymous structure, above, with its two asymmetrical bell towers completed in 1778, is one of eleven Roman Catholic cathedrals in Cuba. Designed by Italian architect Francesco Borromini, the building has been described as “music set in stone.”

The Plaza de la Catedral’s eponymous structure, above, with its two asymmetrical bell towers completed in 1778, is one of eleven Roman Catholic cathedrals in Cuba. Designed by Italian architect Francesco Borromini, the building has been described as “music set in stone.” Inside, the cathedral is filled with artworks painted and sculpted, and a huge, stunningly beautiful chandelier. There is whimsy, too: on giant, wooden front doors two delightful anthropomorphic objects — a door knocker and a keyhole – are straight out of Tenniel’s (and Disney’s) Wonderland.

Inside, the cathedral is filled with artworks painted and sculpted, and a huge, stunningly beautiful chandelier. There is whimsy, too: on giant, wooden front doors two delightful anthropomorphic objects — a door knocker and a keyhole – are straight out of Tenniel’s (and Disney’s) Wonderland.

Nearby streets offer museums and gift shops, experimental graphic arts workshops, bookstores, cigar and liquor stores, and restaurants with live bands.

Nearby streets offer museums and gift shops, experimental graphic arts workshops, bookstores, cigar and liquor stores, and restaurants with live bands.

He and his wife, Mary, shared a large property with about 50 cats, many of them of the polydactyl variety, at Finca Vigia, his home ten miles outside Havana .

He and his wife, Mary, shared a large property with about 50 cats, many of them of the polydactyl variety, at Finca Vigia, his home ten miles outside Havana . The fantastic exteriors are authentic, but maintaining the cars’ motors and finding various mechanical parts to keep the fantasies going requires great ingenuity from the owners. At times, the streets resemble a Hollywood studio backlot for Guys and Dolls or Grease.

The fantastic exteriors are authentic, but maintaining the cars’ motors and finding various mechanical parts to keep the fantasies going requires great ingenuity from the owners. At times, the streets resemble a Hollywood studio backlot for Guys and Dolls or Grease. This “mouth of truth” was once a letterbox in Havana’s main post office, built in the 1700s, now restored as an art gallery. Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday (1953) did the Bocca della Verita bit much better than I.

This “mouth of truth” was once a letterbox in Havana’s main post office, built in the 1700s, now restored as an art gallery. Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday (1953) did the Bocca della Verita bit much better than I. We enjoyed a mesmerizing late afternoon performance at the Danza Teatro Retazos [Dance Theatre Remnant], founded in 1987 under the direction of dance master Isabel Bustos. Andares, which means a gait or walk, is a new work by Ms. Bustos.

We enjoyed a mesmerizing late afternoon performance at the Danza Teatro Retazos [Dance Theatre Remnant], founded in 1987 under the direction of dance master Isabel Bustos. Andares, which means a gait or walk, is a new work by Ms. Bustos. Expressionist dance movements delineate “deities, ceremonies and rituals in a classic Cuban look that recreates typical characters of the Cuban identity [Cubanidad].”

Expressionist dance movements delineate “deities, ceremonies and rituals in a classic Cuban look that recreates typical characters of the Cuban identity [Cubanidad].” The sensuous, continuously moving “walk” of Cuban history by 16 elegantly costumed performers on a small, imaginatively lit stage was excellent. The free form experimental presentation reminded me, with delight, of Rudy Perez and Meredith Monk. For more information:

The sensuous, continuously moving “walk” of Cuban history by 16 elegantly costumed performers on a small, imaginatively lit stage was excellent. The free form experimental presentation reminded me, with delight, of Rudy Perez and Meredith Monk. For more information:

In the current exhibition, large-scale sculpted phantasmagorical creatures stand tall to stare at you with multiple eyes, tongues and heads. Inspired by Mexican mythology and folklore, the designs are scary/zany, the colors dazzling.

In the current exhibition, large-scale sculpted phantasmagorical creatures stand tall to stare at you with multiple eyes, tongues and heads. Inspired by Mexican mythology and folklore, the designs are scary/zany, the colors dazzling.

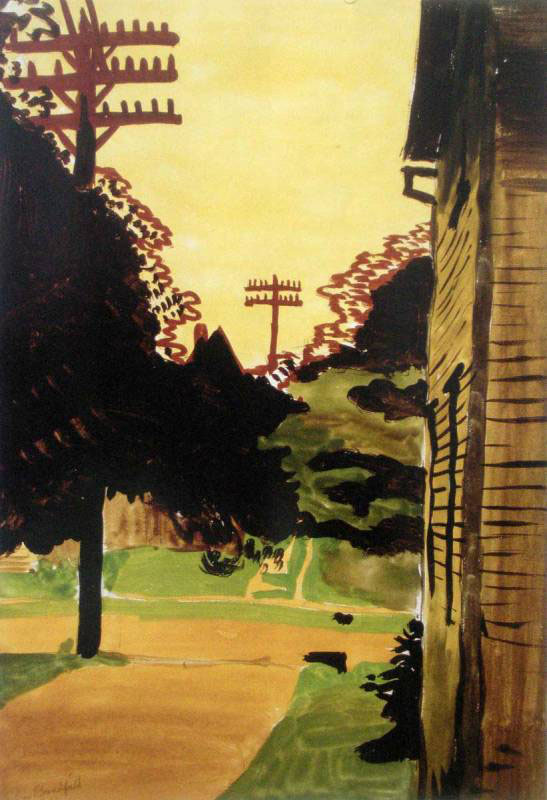

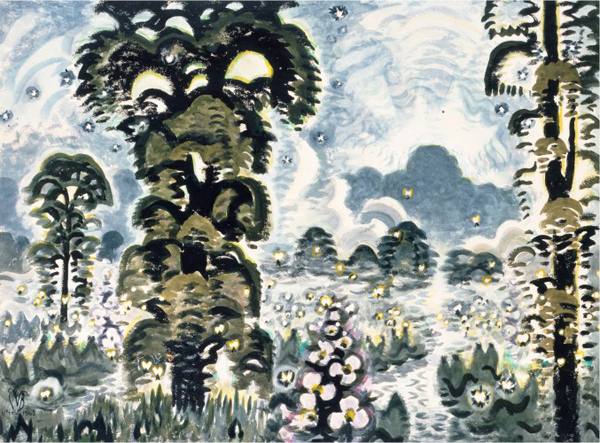

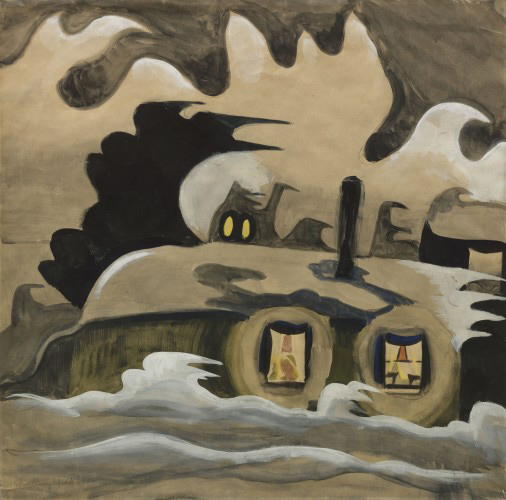

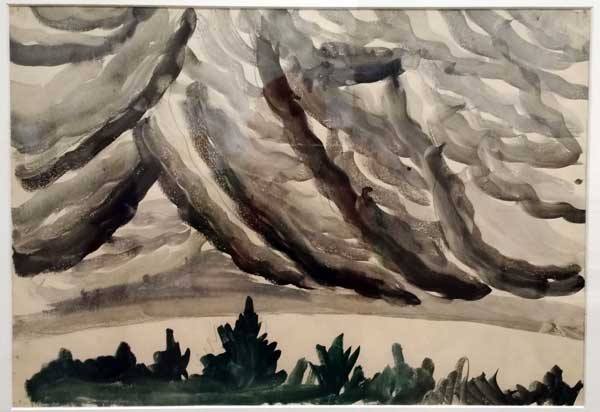

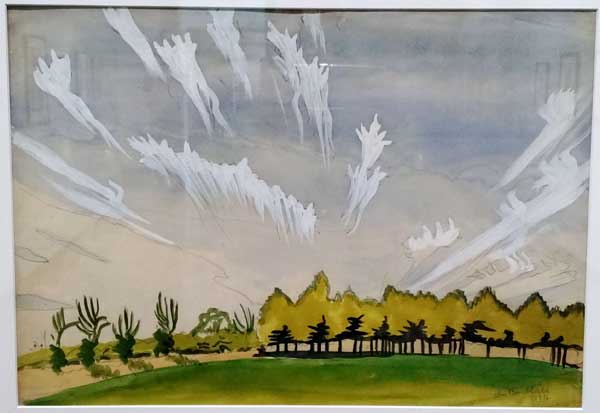

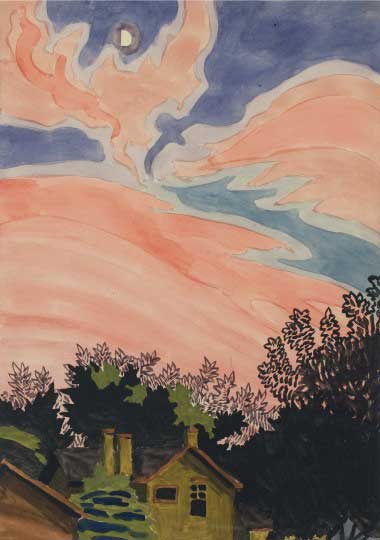

I highly recommend the current exhibition “Charles E. Burchfield: Weather Event” at the Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, N.J. [Sept. 16 through January 7, 2018]. For me, it is always an event, and a privilege, to view up-close and in person the ecstatic, intense, mystical art of the great Burchfield (1893-1967).

I highly recommend the current exhibition “Charles E. Burchfield: Weather Event” at the Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, N.J. [Sept. 16 through January 7, 2018]. For me, it is always an event, and a privilege, to view up-close and in person the ecstatic, intense, mystical art of the great Burchfield (1893-1967).

The backgrounds he complimented may have been in Grizzly Golfer, a 1951 Mr. Magoo short, above and below, directed by Pete Burness and designed by Abe Liss. (Thanks to Adam Abraham, author of When Magoo Flew, for suggesting the title.)

The backgrounds he complimented may have been in Grizzly Golfer, a 1951 Mr. Magoo short, above and below, directed by Pete Burness and designed by Abe Liss. (Thanks to Adam Abraham, author of When Magoo Flew, for suggesting the title.)

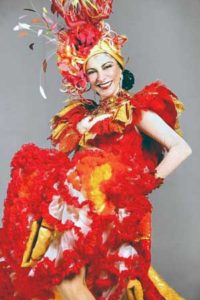

The sisters became enormously popular in Brazil and Argentina, and throughout their professional and personal lives were always supportive of each other. The sisters’ generosity toward each other and loving bond continued even after Carmen became internationally famous in Hollywood films as the spectacularly vital star nicknamed “The Brazilian Bombshell.”

The sisters became enormously popular in Brazil and Argentina, and throughout their professional and personal lives were always supportive of each other. The sisters’ generosity toward each other and loving bond continued even after Carmen became internationally famous in Hollywood films as the spectacularly vital star nicknamed “The Brazilian Bombshell.”

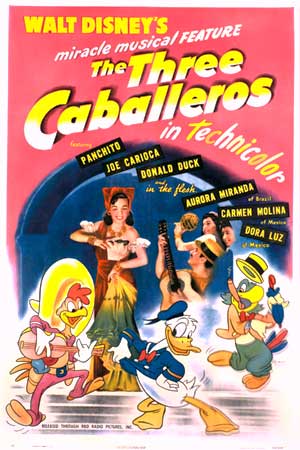

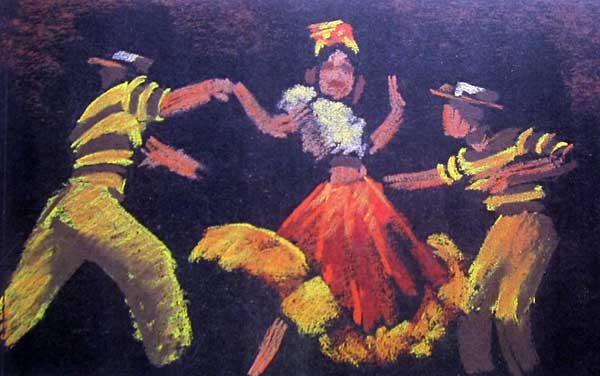

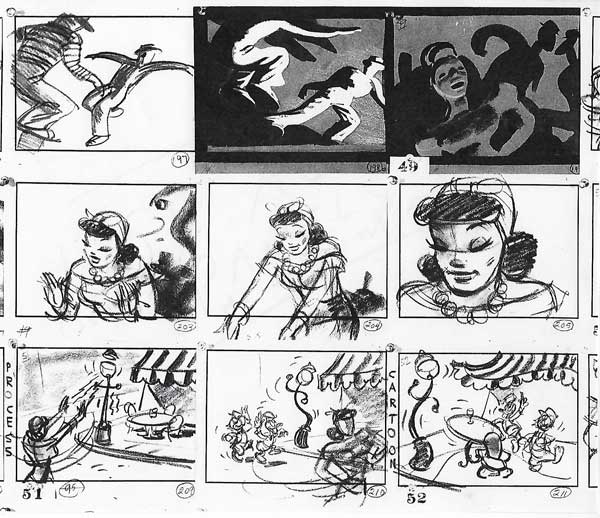

The Three Caballeros was a major breakthrough for a special effect that originated in cinema’s earliest days: combining live-action and animation.

The Three Caballeros was a major breakthrough for a special effect that originated in cinema’s earliest days: combining live-action and animation.

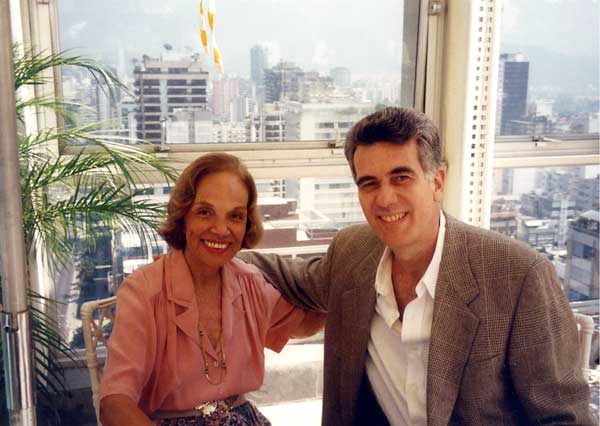

In the summer of 1995, film historian/curator Fabiano Canosa, a true Carioca (native of Rio de Janeiro), invited me to guest curate a program for the Mostra Rio Film Festival, celebrating the 50th anniversary of The Three Caballeros. The screening would also salute Aurora Miranda, by then a beloved Rio legend. Thanks to Disney’s indispensible Howard Green (my Patron Saint of Animation Historians), the studio provided both The Three Caballeros and Ms. Miranda’s screen test.

In the summer of 1995, film historian/curator Fabiano Canosa, a true Carioca (native of Rio de Janeiro), invited me to guest curate a program for the Mostra Rio Film Festival, celebrating the 50th anniversary of The Three Caballeros. The screening would also salute Aurora Miranda, by then a beloved Rio legend. Thanks to Disney’s indispensible Howard Green (my Patron Saint of Animation Historians), the studio provided both The Three Caballeros and Ms. Miranda’s screen test.

We arrived in Rio late Saturday night, exhausted, and awoke the next morning to the beauty of Ipanema Beach. There followed five days of parties, restaurants and visits: O Jardim Botânico; Museu de Arte Moderna’s film department; The Carmen Miranda Museum; a theatrical revue, A Era do Radio, consisting of 1930s/40s Brazilian songs; a tour of Sugar Loaf Mountain; a screening of Buster Keaton films presented by his widow, Eleanor Keaton.

We arrived in Rio late Saturday night, exhausted, and awoke the next morning to the beauty of Ipanema Beach. There followed five days of parties, restaurants and visits: O Jardim Botânico; Museu de Arte Moderna’s film department; The Carmen Miranda Museum; a theatrical revue, A Era do Radio, consisting of 1930s/40s Brazilian songs; a tour of Sugar Loaf Mountain; a screening of Buster Keaton films presented by his widow, Eleanor Keaton. I also visited the balcony of the Hotel Gloria to see where, in 1941, Mary and Lee Blair painted local scenes for Saludos Amigos, which had its world premiere in Rio de Janeiro in 1942.

I also visited the balcony of the Hotel Gloria to see where, in 1941, Mary and Lee Blair painted local scenes for Saludos Amigos, which had its world premiere in Rio de Janeiro in 1942.

She also gifted me with her personal copy of a large illustrated book on Carmen Miranda, published in 1985 in Brazil inscribed, “To John, Carinhosamente. Aurora Miranda, Rio, Sept. 1, 1995.”

She also gifted me with her personal copy of a large illustrated book on Carmen Miranda, published in 1985 in Brazil inscribed, “To John, Carinhosamente. Aurora Miranda, Rio, Sept. 1, 1995.” Aurora attended the festival’s opening looking radiant. At the lavish party afterward, held in the cavernous cultural center Fundição Progresso in the Lapa district, there were great amounts of food and drink, and a wonderful samba band continuously playing 1930s Brazilian music.

Aurora attended the festival’s opening looking radiant. At the lavish party afterward, held in the cavernous cultural center Fundição Progresso in the Lapa district, there were great amounts of food and drink, and a wonderful samba band continuously playing 1930s Brazilian music. As crowds swirled through the huge space, Ms. Miranda treated our small group to a private “concert.” With a beaming smile, she sang quietly so only we could hear. She was delightful, and, too soon, she wished to leave. Walking, with her family and us following, toward the exit, Aurora moved rhythmically through the crowds swaying to the music and continuing to sing quietly.

As crowds swirled through the huge space, Ms. Miranda treated our small group to a private “concert.” With a beaming smile, she sang quietly so only we could hear. She was delightful, and, too soon, she wished to leave. Walking, with her family and us following, toward the exit, Aurora moved rhythmically through the crowds swaying to the music and continuing to sing quietly.