Charles R. (Charley) Bowers (1889-1946) was a brilliantly talented editorial cartoonist and early film animator who, around 1912, began animating shorts featuring comic strip characters created by other artists, such as Happy Hooligan, the Katzenjammer Kids, Bring Up Father, among others. In 1916, he produced the successful Mutt and Jeff animated cartoon series in association with newspaper cartoonist Bud Fisher and pioneer animator/studio owner Raoul Barre.

Energetic, flamboyant, and a bold self-promotor, Bowers was dodgy in his business dealings. Barre was “squeezed out “of the studio he founded, according to historian Donald Crafton. Dick Huemer (1898-1979), who worked at the Barre-Bowers studio as a teenager and years later joined the Disney studio, recalled Bowers “cheated” Barre “and bled the company.”[i]

Huemer also noted, “I don’t think anyone ever abhorred the truth as much as [Bowers] did.”[ii] However, he praised him as “colorful” and “one of the cleverest cartoonists that ever stooped to enter our then rather looked-down-upon animation profession,” an artist whose contribution to the animation scene of the period was “outstanding.”

By the mid-1920s, restless, ambitious, multi-talented Bowers was the director and star of short live-action films. His comedic persona was Keaton-esque, often miming a zany amateur inventor of outlandish contraptions and mechanical objects. He incorporated live-action with stop-motion/puppet animation techniques. His character’s movements are exquisitely subtle, his special effects astonishing and weird. It’s a Bird (1930), Bowers’ only sound film, stars a metal-munching sorta-pterosaur, and was surreal enough to have impressed André Breton.

“In these surrealistic Bowers Comedies,” writes Anthony Scibelli, “eggs hatch Ford automobiles, a Christmas tree grows out of a farmer, a mouse shoots a cat with a revolver, Charley grows a bush which in turn sprouts cats. . . ‘Bowers can conceive the most glorious idiocy,” noted a contemporary review. ‘He is a master of camera wizardry. Every short feature bearing his name proves the camera is a monumental liar.’”

A marginal figure at the end of the silent era, Bowers and his films were forgotten for decades. But they continue to be rediscovered every few years. In the late 1960s, archivist Raymond Borde of the Toulouse Cinémathèque in France found many of Bowers’ “lost films;” additional materials were located by The Library of Congress, Národní filmový archiv, EYE Film Institute, Cinémathèque française, MoMA, and many other archives and collectors throughout the world, including Louise Beaudet, film curator and head of the Animation Department at the Cinematheque Quebecoise. On Nov, 22, 1983, she discussed the odd life and career of this “notorious figure of animation’s early days, considered one of the cleverest cartoonists and animators of his time,” and presented six rare Bowers films at BAMPFA (U of C, Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive).

One of the most passionate and intrepid archivists of Charley Bowers films and their preservation is historian Serge Bromberg. Through his company Lobster Films/Blackhawk Films, he has many times, over the years, literally rescued Bowers films from being destroyed.

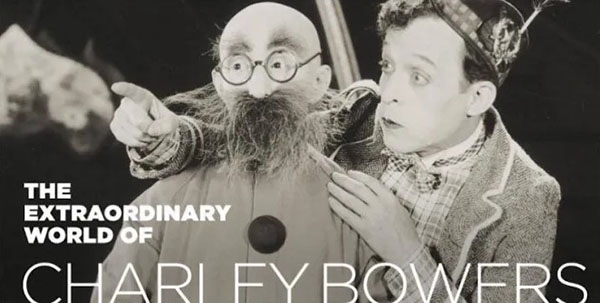

The superb results of his efforts can be seen in Bromberg’s Blu-ray/DVD compilation and scholarly accompanying booklet, THE EXTRAORDINARY WORLD OF CHARLEY BOWERS, as written about in a July 22, 2019 blog posting by Leonard Maltin (“The Amazing Charley Bowers is Discovered – Again!”).

Click image for Leonard’s review:

A showcase of Bowers’ draftsmanship and animation prowess is a 1923 book he wrote and illustrated: Charles Bowers Movie Book, published by Harcourt, Brace & Company. “Mother Goose” was the first of a proposed series of four so-called “Toy-Flip” books.

Alongside the chatty text and profuse illustrations of familiar “Mother Goose” stories are nine folding, colored plates, each containing two sequential drawings. When flipped back and forth quickly, an optical illusion of moving images occurs. For example, the eponymous storybook old lady rides a large white gander with wings down in the top picture; and wings up in the bottom picture.

A simple change, but the imagery works. Bowers’ draftsmanship and animation skills, apparent in his character’s strong poses, are excellent examples of visual storytelling. His inventive artistry is also showcased in detailed, highly amusing line drawings of the nursery rhymes.

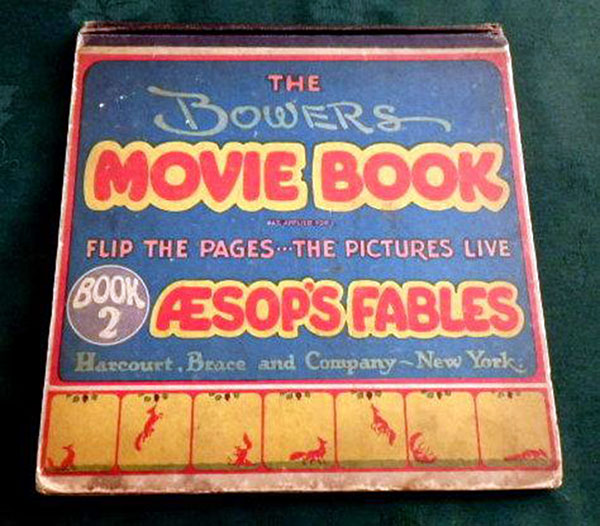

A second book “Aesop’s Fables,” is apparently the only other one of the proposed series to be published. Here is an image of the cover:

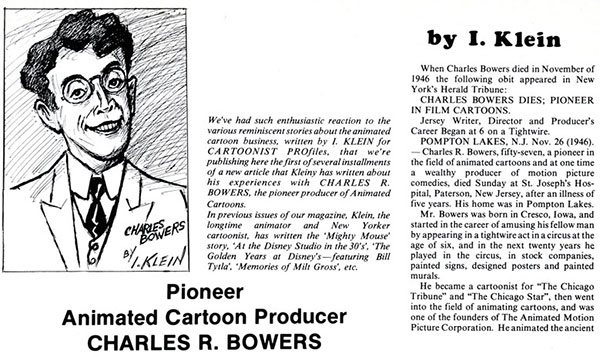

For more eyewitness information on Charles Bowers, see below a three-part essay by I. Klein (1897- 1986), former Disney animator and New Yorker magazine cartoonist, who at age 21, animated at the Barre-Bowers studio.

[i] Before Mickey, The Animated Film 1898-1928, p.199.

[ii] AFI Report, Summer 1974, p.17

Hits: 254