Bottom row, Terry Thoren; unknown; Jerry Beck; Charles Solomon; Will Ryan. Click here to enlarge.

In 1988, I was the Guest Curator of an animation symposium held at Universal Studios in Los Angeles, the second in a series of three annual conferences on “The Art of the Animated Image.” Each was financed through the generosity of cartoon producer Walter Lantz (1899-1994) and the American Film Institute.

For “Storytelling in Animation,” the topic selected for the one-day conference held on Saturday, June 11, 1988, I wanted to offer attendees a wide-ranging overview of the subject. Looking back, after nearly thirty years, it was a never-to-be-repeated moment, when animation stood on the cusp of radical change.

The conference drew together, on stage and in the audience, veterans of the silent film era and the golden age of the Hollywood cartoon; experimental animators; animation historians and authors; and newcomers finding their way at the dawn of CGI and what would be the final burst of Disney hand-drawn animation. Film clips illustrated the discussions.

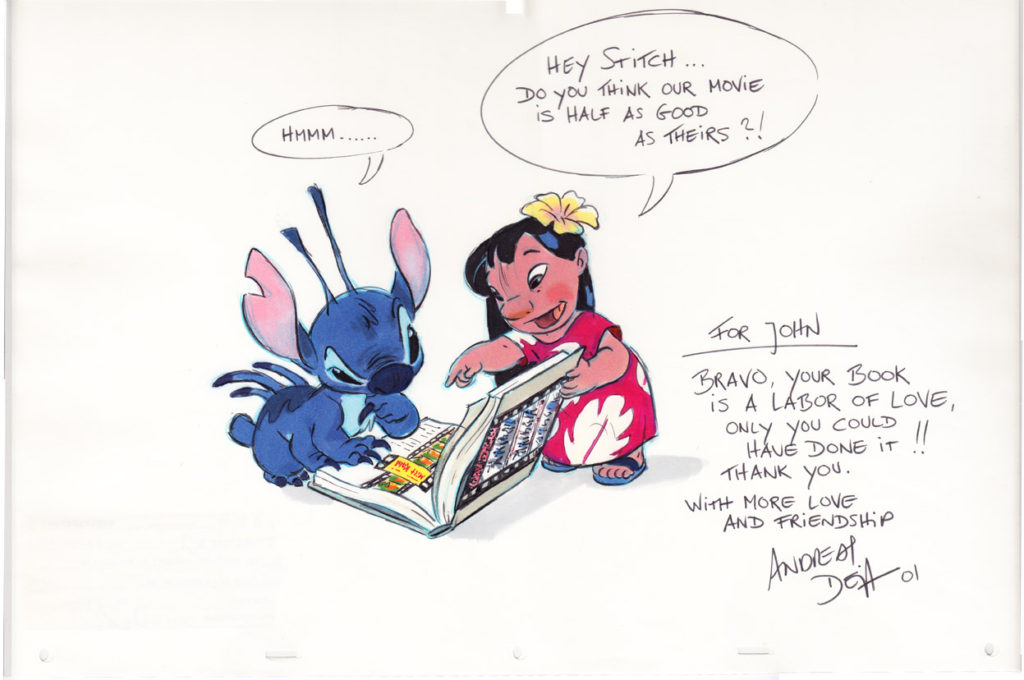

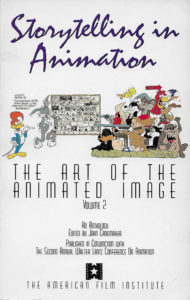

Still photos illustrating this post show some of the event’s participants and audience members. Though the symposium was not videotaped or filmed, an anthology that I edited (Storytelling in Animation: The Art of the Animated Image, Vol. 2) was published in conjunction with the conference. It contains articles on aspects of animation storytelling, as well as selected transcripts of speeches, panel discussions and interviews.

Still photos illustrating this post show some of the event’s participants and audience members. Though the symposium was not videotaped or filmed, an anthology that I edited (Storytelling in Animation: The Art of the Animated Image, Vol. 2) was published in conjunction with the conference. It contains articles on aspects of animation storytelling, as well as selected transcripts of speeches, panel discussions and interviews.

Available through out-of-print online dealers, here are the book’s chapters:

- Introduction – John Canemaker

- Disney’s Pigs Is Pigs: Notes from a Journal, 1949-1953 – Leo Salkin

- Some Observations on Non-Objective and Non-linear Animation – William Moritz

- In the Matter of Writers and Animation Story Persons – Harvey Deneroff

- Frustration – Shamus Culhane

- Storytelling as Remembering: Picturing the Past in Caroline Leaf’s THE STREET – Thelma Schenkel

- A Conversation with Caroline Leaf – Moderated by John Canemaker

- Computers, New Technology and Animation – Moderated by James Lindner, with John Lasseter, Tina Price and Carl Rosendahl

- Studio Approaches to Story – Moderated by John Canemaker, with Bill Peet, Joe Ranft, Jerry Rees and Peter Schneider

- Still is the Story Told: Disney and Story – Robin Allan

- Animation is a Visual Medium – Charles Solomon

- Who Framed Roger Rabbit: The Presence of the Past – Susan Ohmer

- The Little Girl/Little Mother Transformation: The American Evolution of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs – Karen Merritt

- Walt Disney’s Peter Pan: Woman Trouble on the Island – Donald Crafton

It was an exhilarating, informative, fun day. I recall, with great fondness, Hicks Lokey (1904-1990) showing Don Crafton and me some of his animation sketches for Dumbo’s Pink Elephants and Fantasia’s Dance of the Hours; and meeting Frank Paiker (1909-1989), cameraman at J.R. Bray’s studio in the 1920s — where he met Walter Lantz — and later became a technical supervisor at Hanna-Barbera Studios.

It was a thrill to meet Bill Peet (1915-2002), one of Walt Disney’s greatest story artists. On his panel (“Studio Approaches To Story”), he spoke in a raspy whisper, due to throat cancer, but everything he said was pure gold.

For example:

The first thing you have to have is a set of characters that can carry you through the story once they’re established. That’s the most important part. It’s like a train leaving the station without passengers: if you don’t have characters from the word go, you don’t have the story really started . . .

. . . for animation, you need strong, definite personalities, so that you can have broad and explicit action, and they’ll be no doubts what your characters are thinking. In animation, we’re not trying to duplicate live-action or realism. We’re trying to make it larger than life. We want exaggerated actions and attitudes.

Peet often disagreed with Disney when they worked together, and he did so again on the Lantz/AFI panel:

One thing I want to say here today: after Walt Disney had made a big success with Snow White, his next thought was to make films more realistic,more impressive, and more pretentious. And I think he was going in the wrong direction. What makes Snow White is the marvelous personalities, and not its attempts at getting more conventional.

I remember he tried multi-plane camera work, and all the technology available at the time, but I still say the charm of animation is the obvious appearance of it. It always has been, no matter how elaborate you can make it. Animation stands alone.

Also on that panel, and in awe of Peet’s creativity, was Joe Ranft (1960-2005), then age 28, who became my close friend. Joe would join Pixar and Toy Story four years later, but he was already considered one of his generation’s finest story artists.

When I asked him “how sacred” should the original story material for a film be, Joe responded:

I see it as a jumping-off point, and I try to maintain fidelity to the original material in spirit while . . . exploring the possibilities of entertainment. We really see that as a storyman’s job; to get as much entertainment as possible. You can veer away from the material, but sometimes you’ll break the essence of what this story is if you go too far away. So you have to go to the edge, and come back.

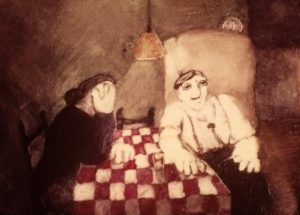

The storytelling power of Caroline Leaf and her award-winning films were honored in a special film tribute. On-stage, she discussed with me The Street (1976), her extraordinary, dark, emotional animated short, which was painted with her fingers frame-by-frame on underlit glass. The story, she recalled, based on a Mordecai Richler book,

was maybe twenty pages, and at first I thought that to be respectful to the writer I should put everything onto film. And I found as I was working, the more I could pare away the words and just work with the imagery and be true to the feeling I was getting in the story, the better it worked on film.

For The Metamorphosis of Mr. Samsa (1977), Caroline focused on one area of the complicated Kafka story:

(H)ow horrible it would be to have a body, or the external part of one’s self that’s seen by the world be different from what’s inside one’s self, and not be able to communicate that.

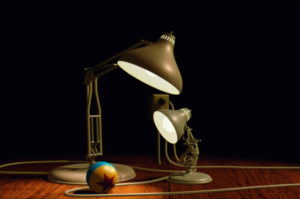

John Lasseter’s comments on the “Computers, New Technology and Animation” panel are fascinating to read today. Here’s a sample:

With computer animation you can do anything if you have the time and the money, but, to me, there are some very strong limitations when you’re dealing with a character. Luxo Jr. (1986) came about when we were learning the system, and I modeled this character of a Luxo lamp . . .

The success of Luxo Jr. was a real surprise to us, to be honest . . . When we premiered it at SIGGRAPH, the computer graphics conference, it got a tremendous reaction, and it was scary in a way.

Jim Blinn, who’s one of the premiere scientists in computer graphics, came running up to me after the screening, and he goes, “John, John, I have a question for you.” And I thought, “Oh boy, umm – I don’t know much about the shadow algorithm or something like that.” And he said, “John was the parent lamp a mother or a father?”

That excited me more than anything else in the world because the film had achieved what I wanted it to: let the story and the characters be the important aspect, not the technology.

During the conference, a couple of aesthetic gauntlets were figuratively thrown. Good grist for discussion, I say.

Dr. William Mortiz (1941-2004), esteemed scholar, teacher, champion of experimental film, and Oskar Fischinger biographer, noted in his sly essay that “No animation film that is not non-objective and/or non-linear can really qualify as true animation.”

. . . watching a drawn coyote crash through walls, fall down stairs, be crushed by falling objects or burned to a crisp by the explosives he holds is certainly not as amazing or funny as seeing Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin or Harold Lloyd of the Keystone Kops do those same stunts live right before our “camera-never-lies” eyes.

Shamus Culhane (1908–1996), animator (he marched the seven dwarfs “Heigh-Ho” in Snow White), successful TV commercial director/producer, could not attend. But he insisted that his brief essay be read aloud before the panel he was invited to participate on. Based on an epiphany Culhane experienced after watching the free-form techniques used in animated films produced at the National Film Board of Canada (sand, clay, pin screen, paint-on-film stock, etc.) his essay attacked what he called the “mind-shackling cel system,” and concluded “it will be a great day for the art form when the last film using cel animation is finished.”

Ka-boom!

Culhane’s confession/diatribe was read in front of and tolerated with icy silence by panelists Lantz, Tendlar, Johnson and Thomas, all traditional hand-drawn, cel technique animators, like Culhane.

But the feisty Irish-American native of Manhattan’s Yorkville proved prescient — two years after the 1988 conference, Disney replaced cels with the Computer Animation Production System (CAPS), and three years after that, John Lasseter started production at Pixar on the CGI feature Toy Story.

Hits: 6686

Walking fast on New York’s magnificent linear High Line Park on a recent brisk February day.

Walking fast on New York’s magnificent linear High Line Park on a recent brisk February day.