Last March, strolling through UCLA’s Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden, my thoughts were focused on my upcoming lecture to the animation graduate students on master animator Vladimir Tytla (1904-1968). The five-acre garden is a serene open-air museum, filled with over seventy international sculptures by Arp, Calder, Smith, Noguchi, Lachaise, and . . .

Suddenly, a nude man, armless — and headless — strode by.

Suddenly, a nude man, armless — and headless — strode by.

It was Auguste Rodin’s magnificent “Walking Man.” Despite lacking a few body parts, the statue breathed life; strong and confident, he swung into a gait with a contrapposto hip twist.

It was Auguste Rodin’s magnificent “Walking Man.” Despite lacking a few body parts, the statue breathed life; strong and confident, he swung into a gait with a contrapposto hip twist.

In a 1976 magazine article, I dubbed the great Tytla “Animation’s Michelangelo,” comparing the Renaissance master’s Sistine Chapel paintings of titanic Sibyls, and his powerful sculptures and drawings of male figures, to Tytla’s extraordinary animation during his brief tenure (1934 – 1943) at Walt Disney’s studio. (Click image at right)

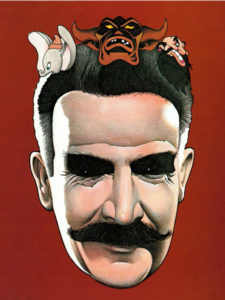

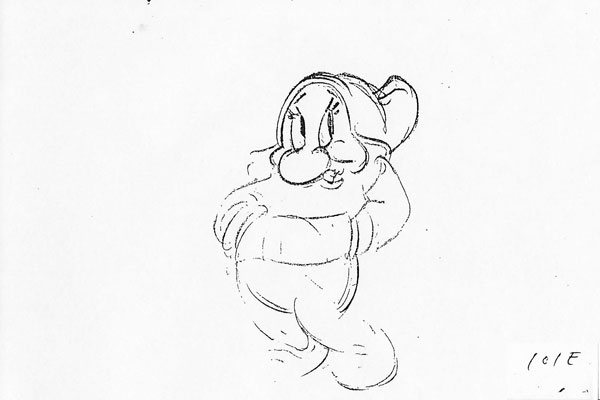

Tytla brought a unique muscularity and power, a physical as well as a psychological dimensionality to his animated characters; for example, the giant devil Chernobog in Fantasia (1940), and bi-polar puppeteer Stromboli in Pinocchio (1940). Even Grumpy, the surly dwarf in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), possesses a dominant, bigger-than-life personality. “Tytla’s work has been a revelation,” Donald Graham, the Disney Studio’s influential art teacher stated on June 21, 1937, less than six months before Snow White’s premiere.

Michelangelo’s preferred art tool was a chisel rather than a brush, and he drew like a sculptor. Rodin’s powerful, rough-textured bronze, cast in 1905, reminded me again of Tytla’s affinity for sculpture. Tytla’s way of “drawing like a sculptor” artfully transferred sequential pencil drawings on paper into three-dimensions, lending them a feeling of physical weight and a range of true emotions.

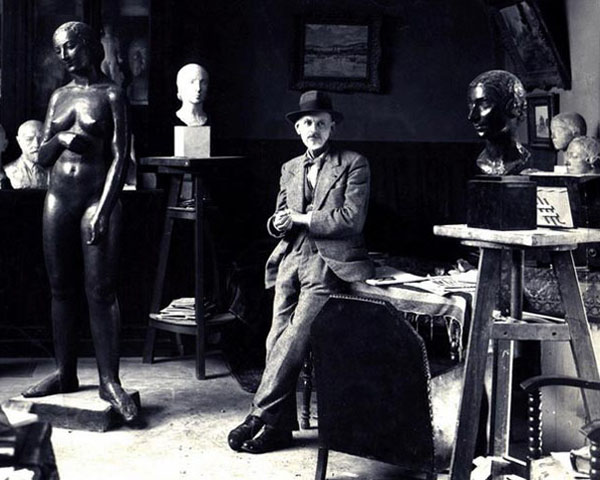

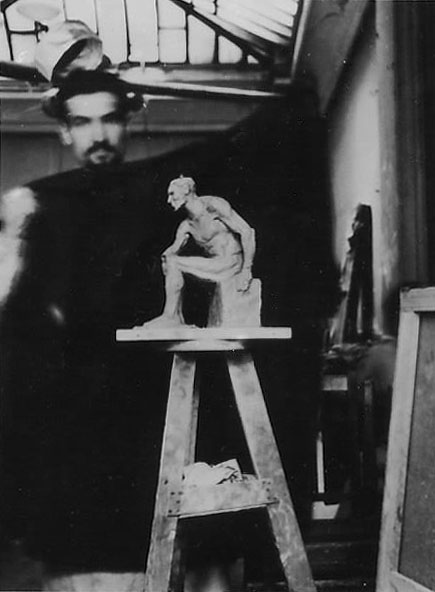

Tytla also had a personal connection to Rodin. In 1929, taking time off from his work in New York City as a well-paid, facile and much-admired animator at Paul Terry’s studio, Tytla traveled to Europe to visit museums and take art classes. While in Paris, he briefly studied sculpture in a workshop taught by Charles Despiau (1874-1946), a fine draftsman who, in 1907, became Rodin’s assistant for seven years.

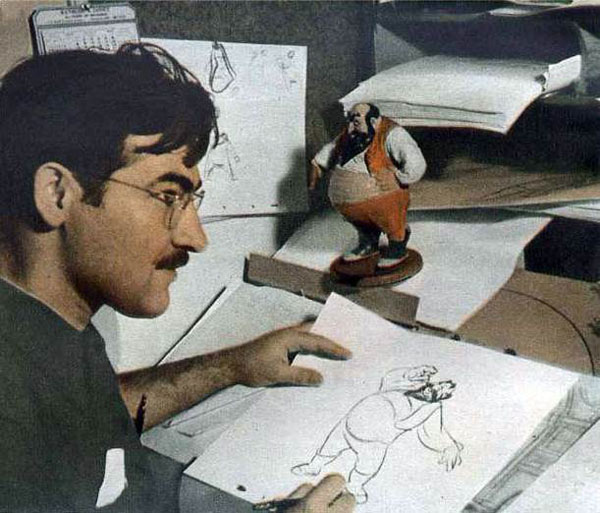

According to Tytla’s friend, animator Art Babbit, Despiau told the 25-year old Tytla, above, that his sculpture held a “Daumier-like quality.” The exigencies of animation production necessitate a certain streamlining, of form. Perhaps Tytla’s sculpting attempts pleased Despiau because he ultimately rejected his mentor Rodin’s style of intense Romanticism for the simplicity of Neoclassical sculpture.

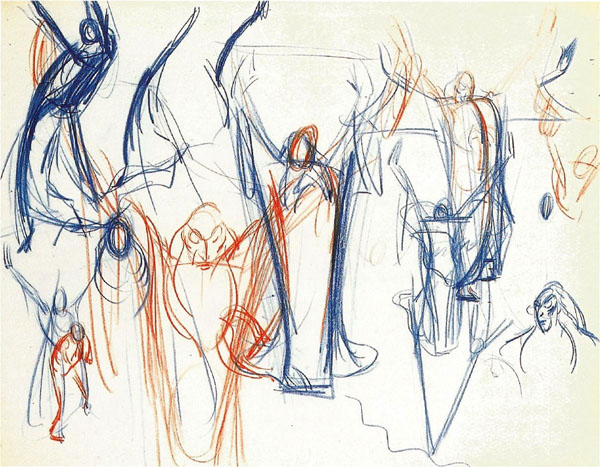

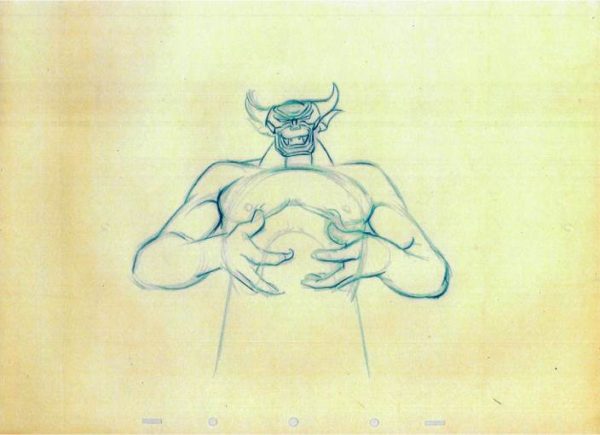

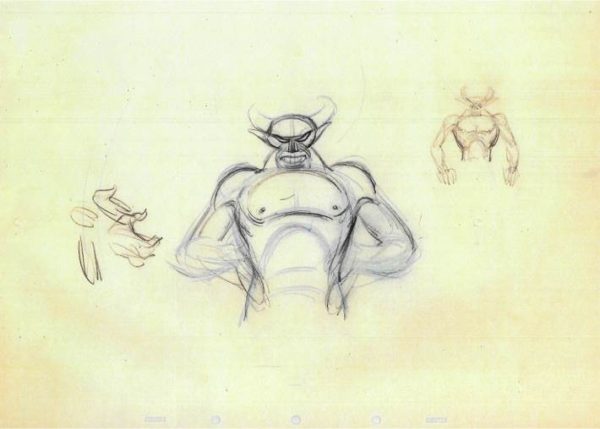

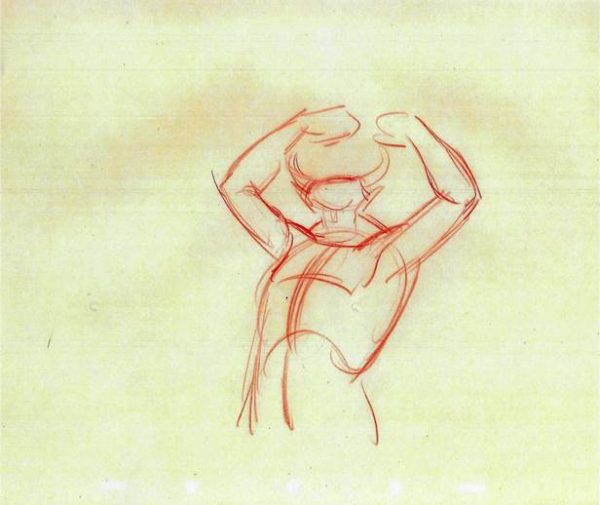

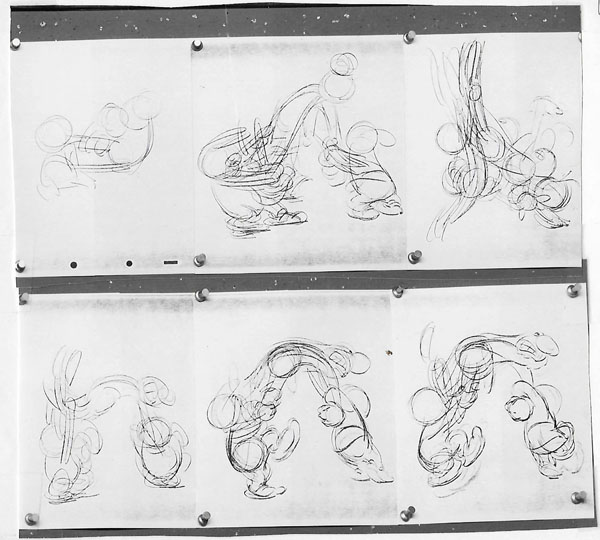

In hand-drawn animation, paring down a character to expressive “animate-able” graphic forms is essential. This process is visible on a single sheet of Tytla’s preliminary sketches for a climatic gesture in The Sorcecer’s Apprentice section of Fantasia.

Nearly a dozen of Tytla’s expressive scrawls decipher Moses-like bodily actions (in long-shot, medium and close-up) employed by the Sorcerer (Yen Sid) parting the waters in his flooded cave, an accident of ill-used magic caused by a disobedient apprentice (Mickey Mouse).

Tytla’s dynamic spidery lines are X-rays revealing a superbly creative animator’s mind. His sculpting lines restlessly search for strong, active, storytelling poses. They contain a sculptural quality reminiscent of Wharton Esherick (1887-1970), who referred to his wood sculptures as “three-dimensional drawing.”

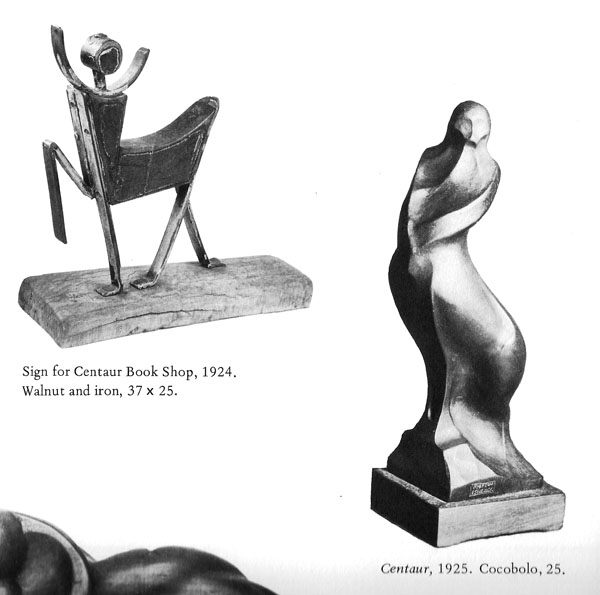

Esherick’s elegant conceptual sketch, circa 1930, for an unfinished sculpture of conductor Leopold Stokowski reaching for a high note and gesturing (sans baton, as always) is similar to Tytla’s search for Yen Sid’s magical water-quelling gesticulation.

Esherick’s imagination, wit and spontaneity are also found in Albert Hurter-like doodles for a colophon for the Centaur Press in 1924.

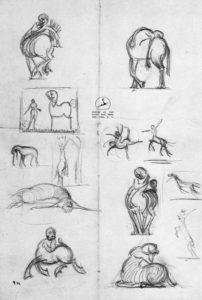

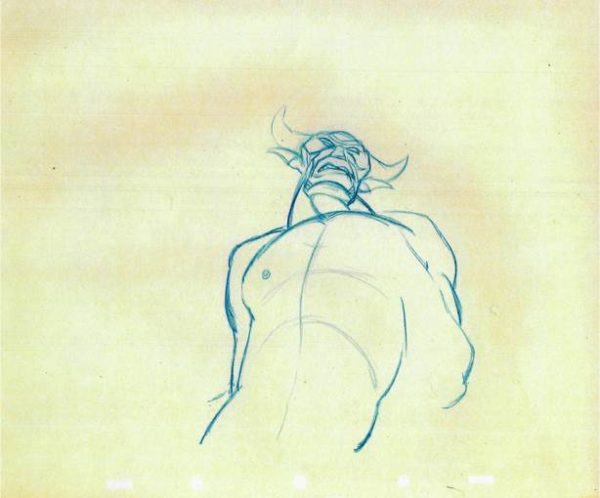

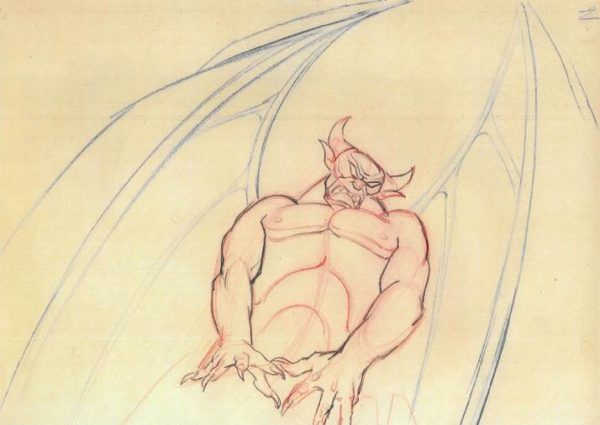

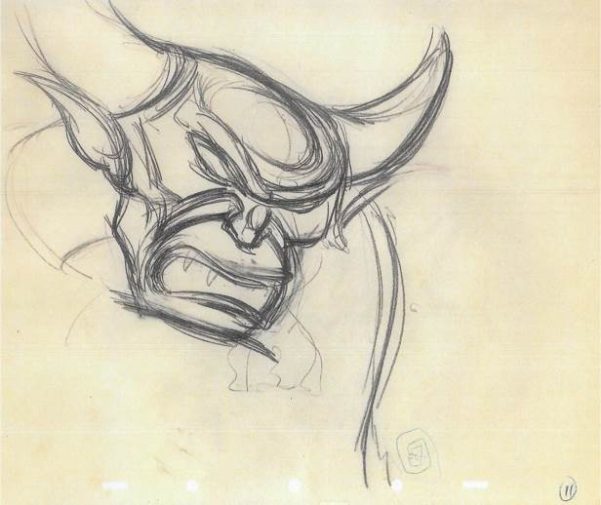

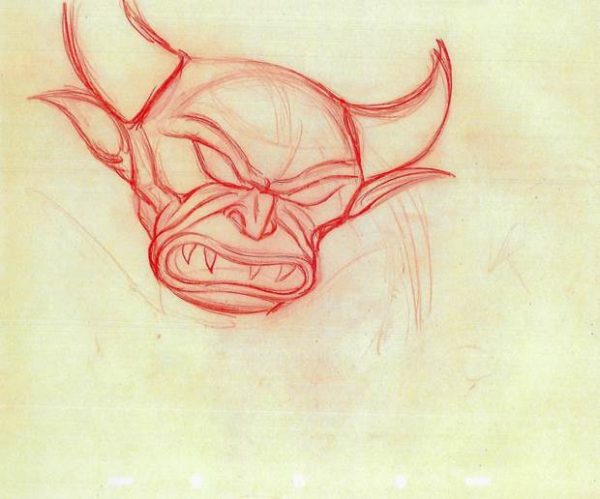

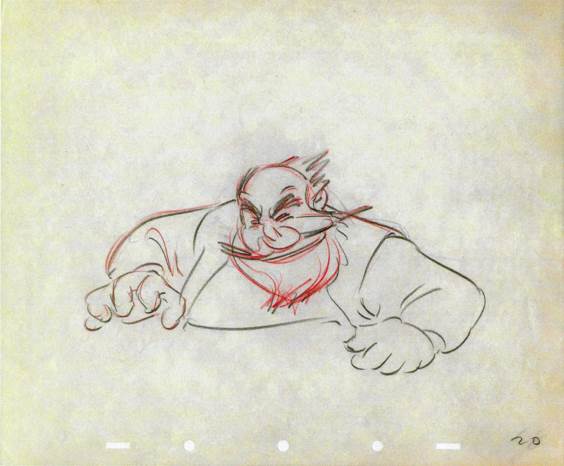

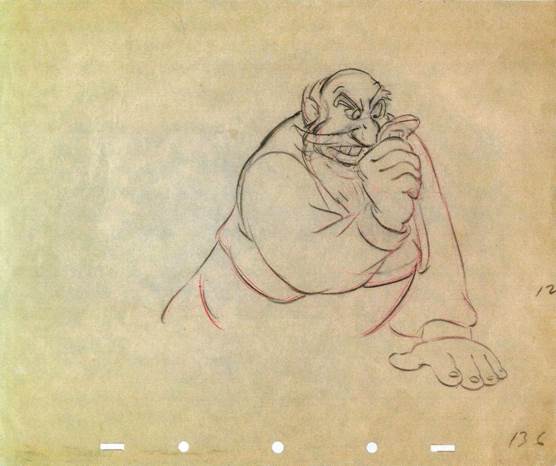

Tytla’s rough preparatory sketches for Chernabog, the giant Bald Mountain devil in Fantasia, impress with their virile shaping, as if they were ready to be chiseled in stone or whittled in wood, instead of drawn.

Tytla’s description (to animation historian John Culhane) of his creative approach to the magnificent devilish assignment is revealing: “I imagined that I was as big as a mountain and made of rock and yet I was feeling and moving.” Sounds to me like Michelangelo or Rodin or Esherick talking.

Tytla’s description (to animation historian John Culhane) of his creative approach to the magnificent devilish assignment is revealing: “I imagined that I was as big as a mountain and made of rock and yet I was feeling and moving.” Sounds to me like Michelangelo or Rodin or Esherick talking.

When Tytla began to animate his characters, “it is obvious that he does not animate forms, but forces,” noted Graham to a Disney art class in 1937.

Tytla is the first animator who has consistently carried this principle throughout his animation — drawing symbols of forces . . . As soon as these forces are under control it is possible to create feelings or emotions or reactions in the audience . . . It makes all the difference imaginable if theartist is thinking of his problem from the point of view of force or from the point of view of form. It is all in the conception.

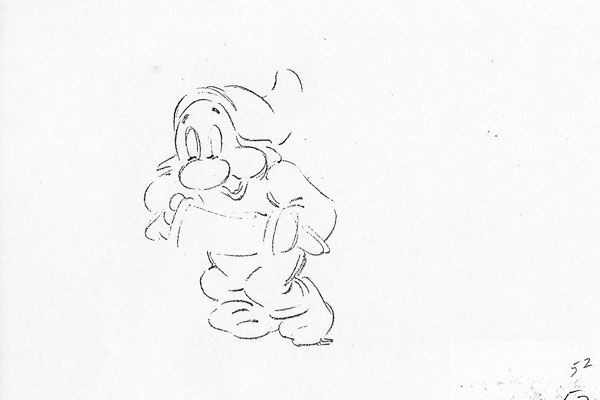

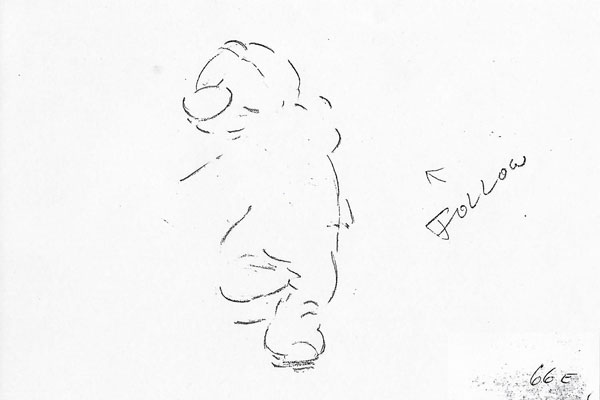

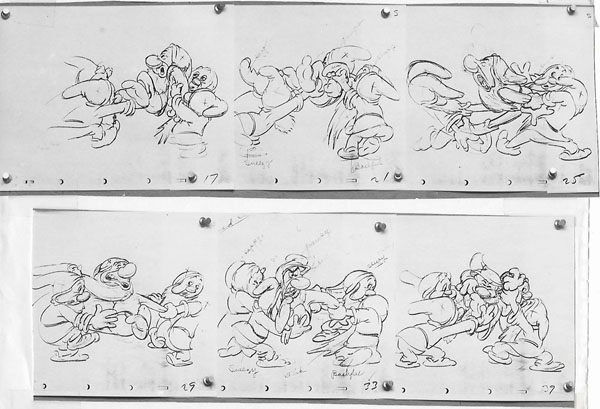

Tytla’s earliest animation drawings of the dwarf Bashful playing a concertina is a fine example of his explorations of action and personality using barely-there symbolic lines to describe forces in the scene.

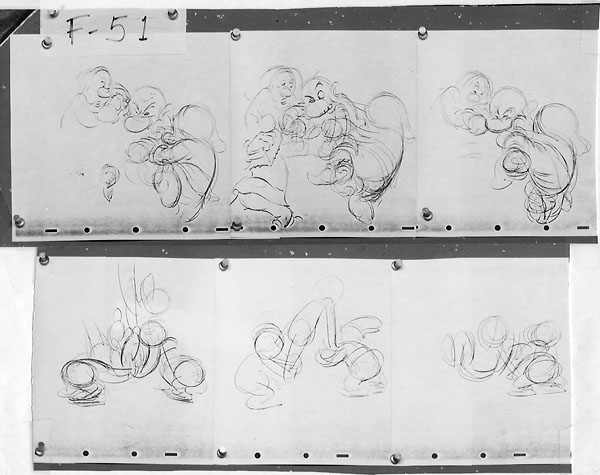

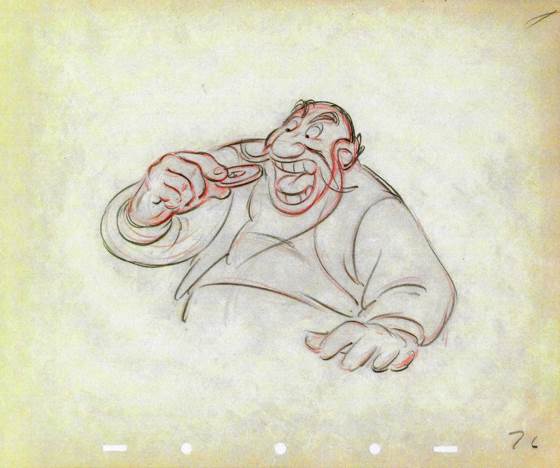

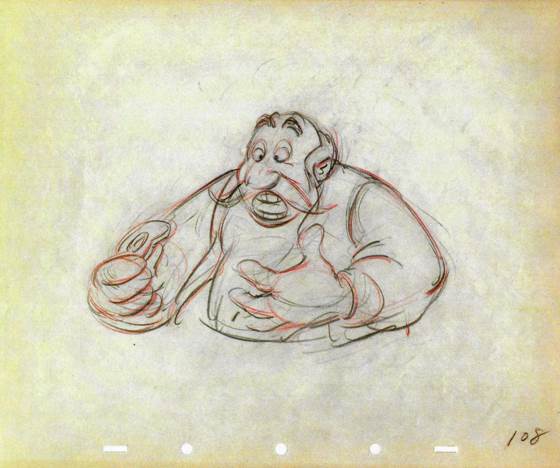

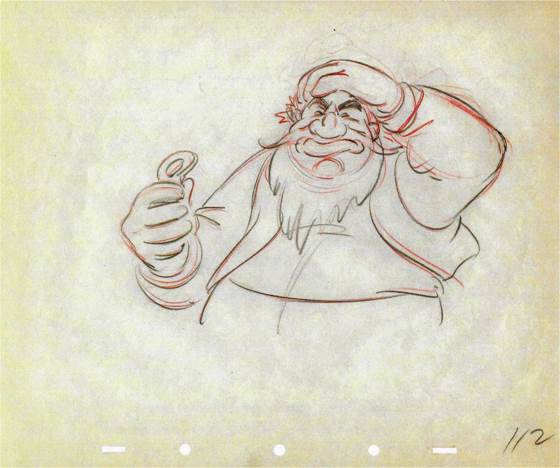

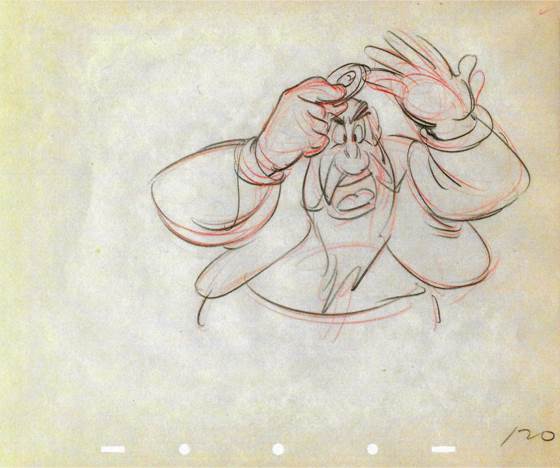

So, too, are a selection of rough scribbles and a second pass of more refined lines and details clarifying a scene in which Grumpy is violently carried to a bathtub. The vitality of the actions depicted is palpable even in still drawings. On the screen, it explodes.

So, too, are a selection of rough scribbles and a second pass of more refined lines and details clarifying a scene in which Grumpy is violently carried to a bathtub. The vitality of the actions depicted is palpable even in still drawings. On the screen, it explodes.

“Vitality in a single drawing is something you don’t buy in a drug store,” Tytla said in 1936. “The whole thing in animation, as in any of the arts, is the feeling and vitality you get into the work.” He also believed that the function of animated cartoons is “not to make the stuff look too damned naturalistic.”

In a Graham art class on June 28, 1937, Tytla suggested to the new studio recruits:

You must phrase, or force or define so that the eye always follows. Very often you must do things you might call bad drawing in order to accent or force . . . to get a certain mood or reaction across . . . In itself [one drawing] is nothing – just a continuation of a vast whole. . . If you always try to keep perfect form you will not get the feeling across — it will be something . . . without any flavor.”

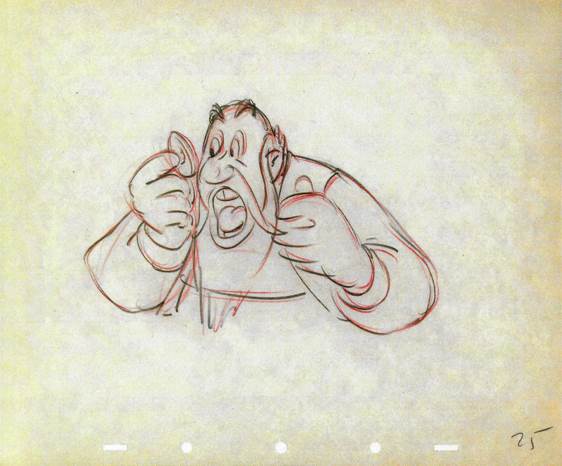

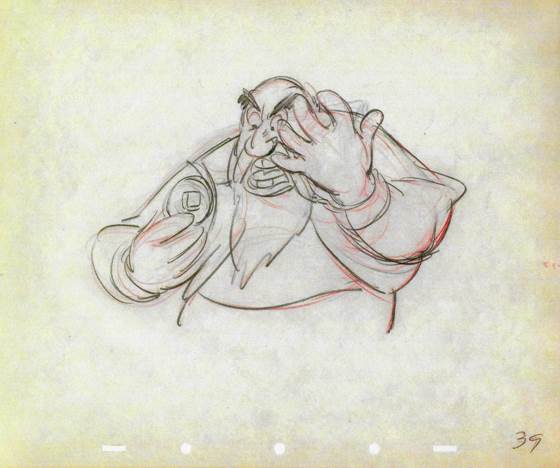

Exaggeration, one of animation’s basic principles, Tytla touted this way:

You can force or accent a hand and throw it way out and bring it back down . . . You can give a drawing an accent – you can twist an eyebrow or a mouth — you can force or accent it – you can do something to the little character’s shoulder or chest; but it is a continuous flow, and it always comes back to its original shape.

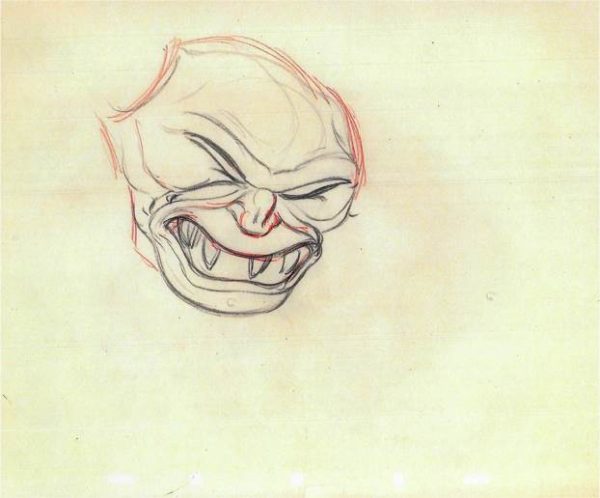

That is what Tytla did: after wild distortions defining the emotional state of mad kidnapper Stromboli, he brings the character back to his original shape.

Tytla also looks for, and usually finds, ways that give his character someplace to go. Moving Stromboli from one side of the screen to the other in most scenes adds visual variety and texture to the moving composition. His work is not static; it is progressive.

Tytla also looks for, and usually finds, ways that give his character someplace to go. Moving Stromboli from one side of the screen to the other in most scenes adds visual variety and texture to the moving composition. His work is not static; it is progressive.

With Mozartian directness, emotions flowed from Tytla’s brain into his pencil and onto paper. He was a great and unique animator who brought a sculptor’s sensibility into graphic lines, which are, as Donald Graham described it, “full of movement . . . the rhythmic movement of line . . . this stuff has vitality!”

For more information on Vladimir Tytla, see the illustrated catalogue for Vladimir Tytla – Master Animator, the exhibition I curated for the Katonah Museum of Art (September 18-December 31, 1994) here:

For a montage of great Tytla scenes, visit:

and

Special thanks to Howard Green and Charles Solomon.

All Disney Images are ©Disney and are shown here for educational and inspirational purposes only.

Hits: 14200