In Rio de Janeiro in the 1930s, the vibrant and beautiful Miranda sisters — Carmen (1909-1955) and Aurora (1915-2005) — performed solo and often together in stage shows, film, radio and recordings.

One of their joint appearances was the 1936 Brazilian revue film Alô Alô Carnaval, (above) in which Carmen and Aurora performed “As Cantoras do Rádio.”

The sisters became enormously popular in Brazil and Argentina, and throughout their professional and personal lives were always supportive of each other. The sisters’ generosity toward each other and loving bond continued even after Carmen became internationally famous in Hollywood films as the spectacularly vital star nicknamed “The Brazilian Bombshell.”

The sisters became enormously popular in Brazil and Argentina, and throughout their professional and personal lives were always supportive of each other. The sisters’ generosity toward each other and loving bond continued even after Carmen became internationally famous in Hollywood films as the spectacularly vital star nicknamed “The Brazilian Bombshell.”

By the mid-1940s, Carmen Miranda was the highest paid woman in the United States, a world-famous symbol (albeit a stereotypical one) of America’s World War II Good Neighbor Policy toward Latin America. During her career, she always maintained strong ties with her family in Brazil, especially Aurora.

For example, in 1940 Carmen presented her sister with a gold-trimmed wedding dress, and then gifted the newly-married Aurora and her husband, Gabriel Richaid, a businessman, with a honeymoon in America – and they ended up staying for a dozen years. Carmen was delighted to have them, and her mother, sharing her spacious Beverly Hills home; once again they were a close-knit family, just like in Rio.

Encouraged by Carmen, Aurora began appearing in Earl Carroll revues in Los Angeles and in films such as Phantom Lady and Brazil, both of which were released in 1944.

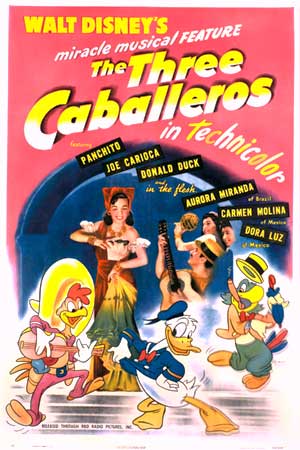

In October 1942, Aurora filmed a screen test for The Three Caballeros (released in 1945). It was Walt Disney’s second feature film promoting the government’s “Good Neighbor” initiative for positive hemispheric relations. (For definitive information on Disney’s Good Neighbor films 1941-1948, read South of the Border with Disney by J.B. Kaufman, Disney Editions, 2009)

The Three Caballeros was a major breakthrough for a special effect that originated in cinema’s earliest days: combining live-action and animation.

The Three Caballeros was a major breakthrough for a special effect that originated in cinema’s earliest days: combining live-action and animation.

Now using Technicolor and new camera technologies the studio had developed, Disney artfully mixed cartoon fantasy and human performers in complex ways never attempted before.

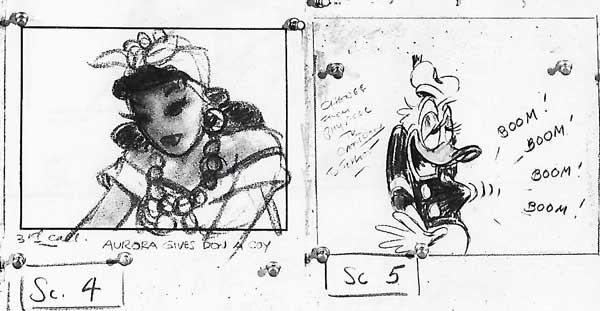

For Aurora’s screen test, Carmen supplied her sister with a skirt she wore in Weekend in Havana (20th Century Fox, 1941), and for the final soundtrack recording, she provided Disney with her personal samba band, Bando da Lua (who were under contract with her at Fox).

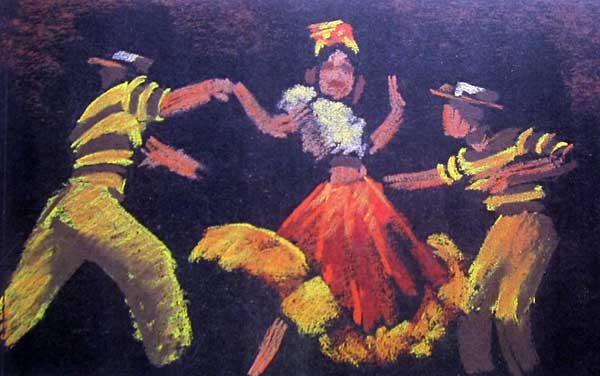

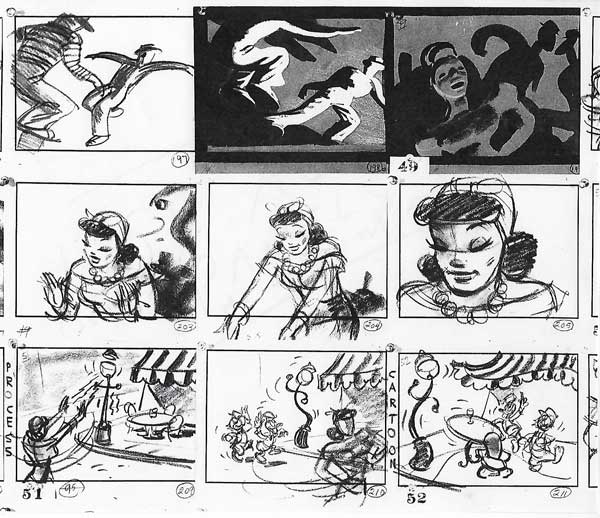

In The Three Caballeros, Aurora Miranda gives a saucy, joyful performance singing “Os Quindins de Yayá,” while dancing with a Brazilian parrot named Jose Carioca and ignoring a lustful Donald Duck (though, eventually, she kisses him). The entire sequence is a technical tour de force set to a samba beat involving numerous musicians, singers and dancers including two men who morph into fighting cocks.

For the finale, Aurora casts a sexy sorceress’ spell on the entire city of São Salvador in the Brazilian state of Bahía, literally bringing the streetlamps, road and buildings of the town alive in some of the giddiest, most surreal, and iconic imagery in the Disney canon.

Here is a selection of original story sketches that shows how the Disney artists visualized this sequence, along with notations indicating when live-action and animation were to be combined (“process”) , and when only animation was to be used (“cartoon”) :

In the summer of 1995, film historian/curator Fabiano Canosa, a true Carioca (native of Rio de Janeiro), invited me to guest curate a program for the Mostra Rio Film Festival, celebrating the 50th anniversary of The Three Caballeros. The screening would also salute Aurora Miranda, by then a beloved Rio legend. Thanks to Disney’s indispensible Howard Green (my Patron Saint of Animation Historians), the studio provided both The Three Caballeros and Ms. Miranda’s screen test.

In the summer of 1995, film historian/curator Fabiano Canosa, a true Carioca (native of Rio de Janeiro), invited me to guest curate a program for the Mostra Rio Film Festival, celebrating the 50th anniversary of The Three Caballeros. The screening would also salute Aurora Miranda, by then a beloved Rio legend. Thanks to Disney’s indispensible Howard Green (my Patron Saint of Animation Historians), the studio provided both The Three Caballeros and Ms. Miranda’s screen test.

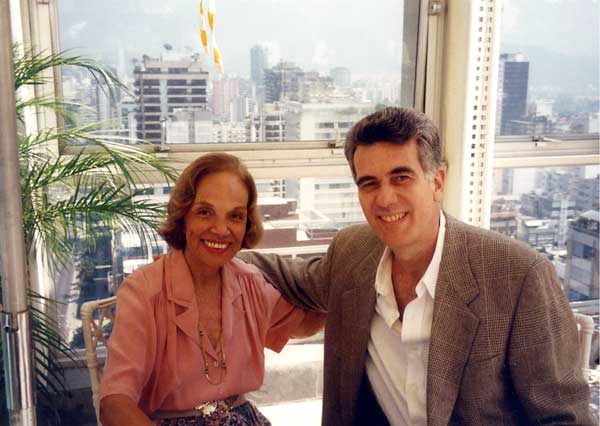

I first met Aurora Miranda in New York on Thursday, August 24, 1995, at the West 95th Street townhouse of filmmakers Helena Solberg and David Meyer, producers of the Carmen Miranda bio/documentary, Bananas is My Business.

The occasion was a buffet dinner for entertainers performing the next evening at an outdoor concert in Lincoln Center called Brazil Fest. The program featured contemporary Brazlian artist singing songs from the samba era ofthe 1930s and 40s, including a special commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the death of Carmen Miranda (in 1955 at age 46) – the highlight of which was a rare singing appearance by her sister.

Aurora Miranda was sitting quietly on a sofa, unassuming and charming, and Joe Kennedy and I spoke briefly with her. Her English was not fluent and we spoke no Portuguese, but with Fabiano’s help we communicated that we would see her again very soon — in fact, within a few days, in Rio de Janeiro.

Aurora was 80 when we met, but was amazingly young-looking and glamorous. Graciously, she signed a photo I brought of her in Three Caballeros, and we all enjoyed the party and warm hospitality of Helena and David.

The next evening, at Brazil Fest in the outdoor theatre of Lincoln Center, it seemed like New York’s entire Brazilian community was there. The large audience knew all the songs and sang the lyrics along with the stage performers and bands. Their feelings were upfront about the performers: cheering wildly for those they loved, but also baying like dogs in mockery of certain crooners.

The evening’s high point came at the finale, when noted Brazilian actress Marília Pêra (1943-2015) appeared. Dressed as Carmen Miranda, Pêra performed a medley of songs associated with her.

Then Pêra introduced her “sister”: Aurora Miranda walked elegantly onstage, and the audience lost it, pouring out their love for her and Carmen with tremendous shouts and cheers.

Especially exciting was the duet Aurora and Pêra sang — “As Cantoras do Rádio,” the very same song Aurora and Carmen had performed on film together some 60 years earlier. People wept openly, filled with saudade — in Portuguese, an expression for feeling nostalgic melancholy and joy at the same time. It was a wonderful evening, and Joe and I hurried home right after the finale to pack for our own trip to Rio the next day.

We arrived in Rio late Saturday night, exhausted, and awoke the next morning to the beauty of Ipanema Beach. There followed five days of parties, restaurants and visits: O Jardim Botânico; Museu de Arte Moderna’s film department; The Carmen Miranda Museum; a theatrical revue, A Era do Radio, consisting of 1930s/40s Brazilian songs; a tour of Sugar Loaf Mountain; a screening of Buster Keaton films presented by his widow, Eleanor Keaton.

We arrived in Rio late Saturday night, exhausted, and awoke the next morning to the beauty of Ipanema Beach. There followed five days of parties, restaurants and visits: O Jardim Botânico; Museu de Arte Moderna’s film department; The Carmen Miranda Museum; a theatrical revue, A Era do Radio, consisting of 1930s/40s Brazilian songs; a tour of Sugar Loaf Mountain; a screening of Buster Keaton films presented by his widow, Eleanor Keaton.

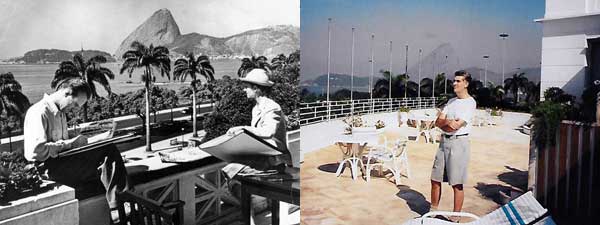

I also visited the balcony of the Hotel Gloria to see where, in 1941, Mary and Lee Blair painted local scenes for Saludos Amigos, which had its world premiere in Rio de Janeiro in 1942.

I also visited the balcony of the Hotel Gloria to see where, in 1941, Mary and Lee Blair painted local scenes for Saludos Amigos, which had its world premiere in Rio de Janeiro in 1942.

On Thursday, August 31, I introduced Aurora Miranda from the stage of the grand, ornate Rio de Janeiro Theatro Municipal, built in 1909. She looked radiant and chic in a patterned black dress. After I told the full house about the film salute to Aurora we would present later that week, she rose from the audience to clamorous applause, stood alone in the spotlight and spoke briefly. Then she laughed and reached out to me to escort her off stage.

The next morning, Joe and I joined the throngs of Caroicas and tourists strolling along the beachfront promenade at Ipanema. Still a bit overwhelmed by the sheer beauty of the setting, we had a sudden surprise when we saw Aurora in the crowd ahead, walking directly toward us from the opposite direction, on her own morning constitutional.

Immediately, we three joined forces and went to breakfast at the Caesar Park Hotel, where we were staying. Aurora and I also participated that week in several press interviews at various locations. Although I did not formally interview her, I did ask her (through an interpreter) about Walt Disney. She was very positive about her experiences with him. A phrase she said more than once was “Disney was full of ideas!”

I said I’d read a quote, supposedly from her, that she “didn’t like to kiss the duck.” She laughed, neither confirming nor denying the anecdote.

The tribute to Aurora took place at Rio’s Cinemathque, and she attended with her family (her son, his wife and children). We screened her Technicolor Disney test without sound, but “Os Quindins de Yaya” was heard in the audience as Aurora sang a cappella to her movie image — a memorable thrill for all in attendance.

Later, she gave me original George Hurrell publicity photo negatives of her posing in costume on a Three Caballeros set, in which an empty space was reserved for a later insertion of a drawing of Donald Duck.

She also gifted me with her personal copy of a large illustrated book on Carmen Miranda, published in 1985 in Brazil inscribed, “To John, Carinhosamente. Aurora Miranda, Rio, Sept. 1, 1995.”

She also gifted me with her personal copy of a large illustrated book on Carmen Miranda, published in 1985 in Brazil inscribed, “To John, Carinhosamente. Aurora Miranda, Rio, Sept. 1, 1995.”

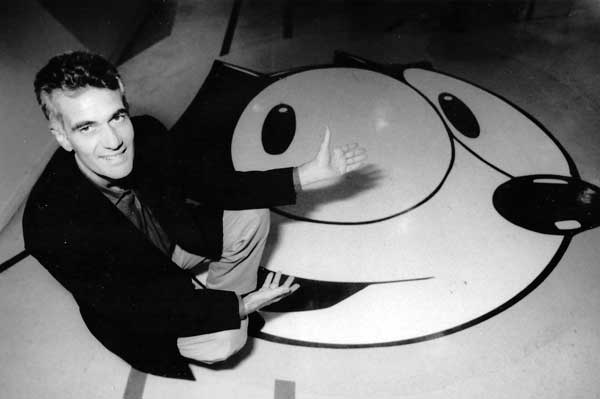

The next year, 1996, Joe and I were again invited to participate in the Mostra Film Festival. This time I curated and hosted a program of Felix the Cat, the cartoon feline whose popularity as a silent film star of the 1920s rivaled Chaplin and Keaton.

Aurora attended the festival’s opening looking radiant. At the lavish party afterward, held in the cavernous cultural center Fundição Progresso in the Lapa district, there were great amounts of food and drink, and a wonderful samba band continuously playing 1930s Brazilian music.

Aurora attended the festival’s opening looking radiant. At the lavish party afterward, held in the cavernous cultural center Fundição Progresso in the Lapa district, there were great amounts of food and drink, and a wonderful samba band continuously playing 1930s Brazilian music.

We sat with Aurora and her family. Knowing so many of the standards being played (and probably having recorded many of them) she sang along spontaneously.

As crowds swirled through the huge space, Ms. Miranda treated our small group to a private “concert.” With a beaming smile, she sang quietly so only we could hear. She was delightful, and, too soon, she wished to leave. Walking, with her family and us following, toward the exit, Aurora moved rhythmically through the crowds swaying to the music and continuing to sing quietly.

As crowds swirled through the huge space, Ms. Miranda treated our small group to a private “concert.” With a beaming smile, she sang quietly so only we could hear. She was delightful, and, too soon, she wished to leave. Walking, with her family and us following, toward the exit, Aurora moved rhythmically through the crowds swaying to the music and continuing to sing quietly.

As she descended an underlit translucent glass staircase to a samba beat, I followed behind. For a moment, I had the strange and wonderful sensation that I am Pato Donald, following the beautiful YaYa, dancing through the streets of Salvador, as she magically brings a sleeping city to life.

Later that week, Joe and I saw Aurora for the last time. She invited us for coffee at her apartment in the upscale Leblon district, adjacent to Ipanema.

Her housekeeper, who Aurora affectionately called “my child,” served us the strong delicious brew. Her apartment was comfortable and sunny, and the walls were filled with pictures of her sister Carmen, the great entertainer. In spite of our mutually halting ways of communicating, we understood how sad Aurora was regarding her sister’s tragic early death in 1955, and how much she still missed her.

She showed us albums of photographs from the 1930s and 40s: her performances with Carmen, and herself as a solo singer and recording artist; Aurora’s brief years in Hollywood (she returned to Brazil in 1952); and her happy, fifty-year marriage to Gabriel Richaid, and their two children Maria and Gabriel.

After I returned to New York, we had a brief correspondence. I was deeply saddened to read of her death in 2005.

Aurora Miranda was a warm, joy-filled spirit and a unique presence on screen and in person. She was an entertainer who brought happiness to many around the world. Though I knew her only briefly, I think of her often, for she made me understand the true meaning of saudade.

Hits: 8933