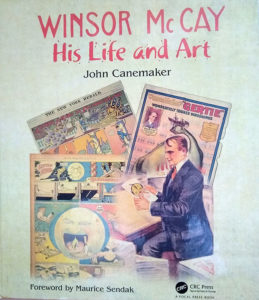

Winsor McCay – His Life and Art, my biography of the innovative pioneer of comic strips and animated films, has been revised twice since Abbeville Press first published it in 1987. In the 2005 Harry N. Abrams edition and, again, in the current 2018 CRC Press/A Focal Press Book edition, I updated and expanded the text to include new information about McCay that had come to my attention in the last three decades.

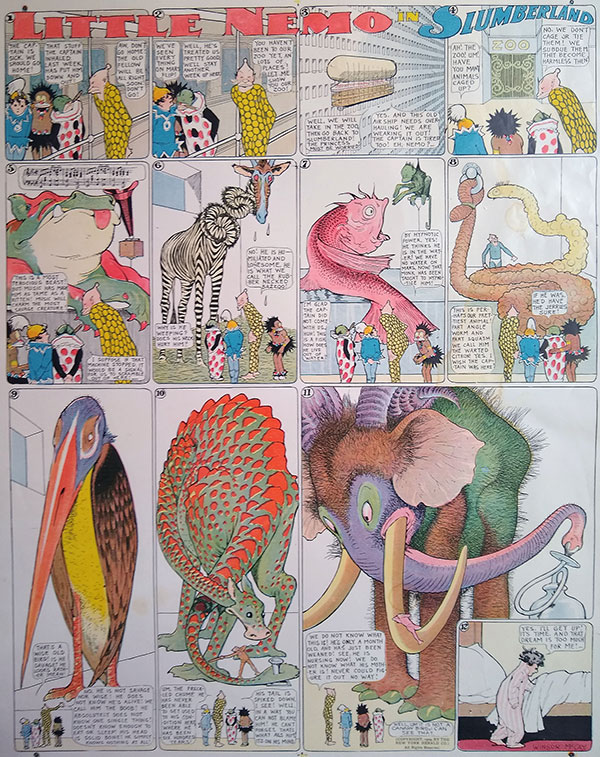

I am particularly pleased about one informational addition in the new CRC/Focal Press edition, concerning a gentleman I first described, in 1987, as merely “a Mr. Hunt of the [New York] Herald color department.” His name had come to my attention in the margin of an original Little Nemo in Slumberland comic strip board, on which Winsor McCay penciled an instructional message in non-photographing blue pencil:

I am particularly pleased about one informational addition in the new CRC/Focal Press edition, concerning a gentleman I first described, in 1987, as merely “a Mr. Hunt of the [New York] Herald color department.” His name had come to my attention in the margin of an original Little Nemo in Slumberland comic strip board, on which Winsor McCay penciled an instructional message in non-photographing blue pencil:

Mr. Hunt,

This is a snow forest. All the trees and foliage are snow. Plenty of purple and blue tones. The only bright color will be in the costume of the figures. An orange sky. The rest all pale blues, pinks and purples. Creme colored [indecipherable] with cold blue shadows.

Mc.

(The strip, which was published on January 21, 1906, had Nemo tunneling through snow while being chased by a polar bear.)

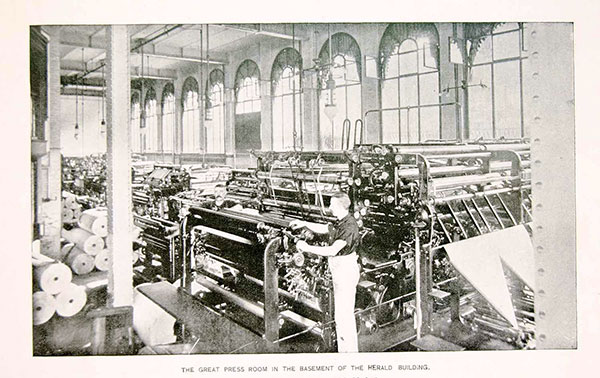

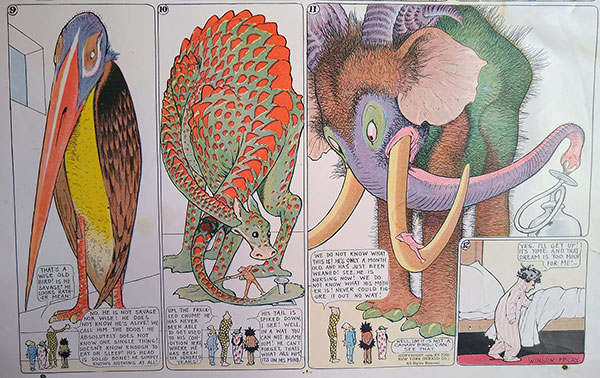

I figured Mr. Hunt was one of the so-called “artists in zinc,” a master of the Ben Day printing process which allowed shading on color pictures for reproduction in the Herald. It was an intricate, labor intensive artistic/mechanical/chemical operation that lent McCay’s Little Nemo and other Herald Sunday comic strips the most subtle, stunningly beautiful array of colors ever seen in early news print.

I later happened upon an April 20, 1914 Herald article,“Exhibit of Color Print Art Pays Tribute to Work Done by the Herald”, which describes in detail the problems of etching on plates of zinc to achieve gradations of light and shade or tone.

The etcher on copper, after great labor, is able to produce this effect with the needle . . . The Ben day process consists in placing a fine meshed, inked screen over the parts of the plate to be shaded and then making dots by passing a roller over it. That portion of the plate which is not to be printed on is protected by a gamboge solution. The screen is regulated by a delicately adjusted gauge, manipulated by a thumb screw, and the ground may be light or dark as the operator thinks best. It is in the various modifications of the process, the placing of dots and lines in greater number where deeper color is desired, and in the soft blending of tones that the artist-artisans of the Herald plant excel.

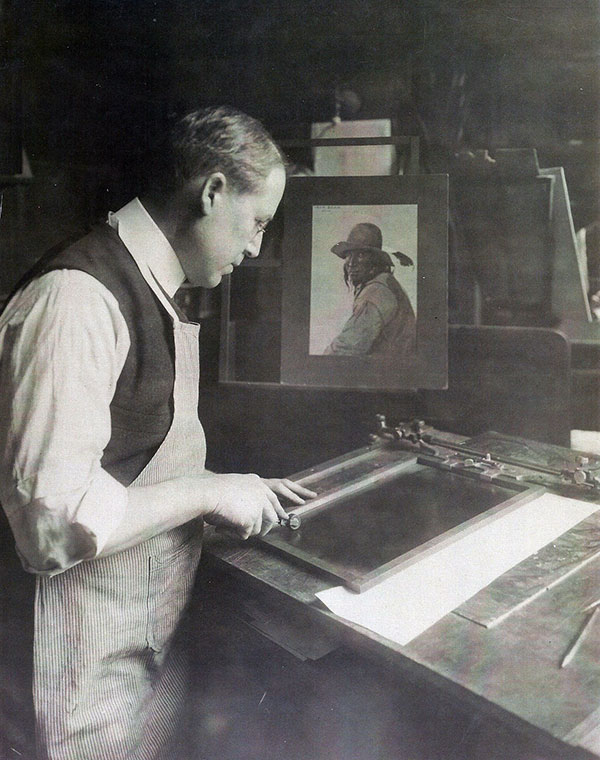

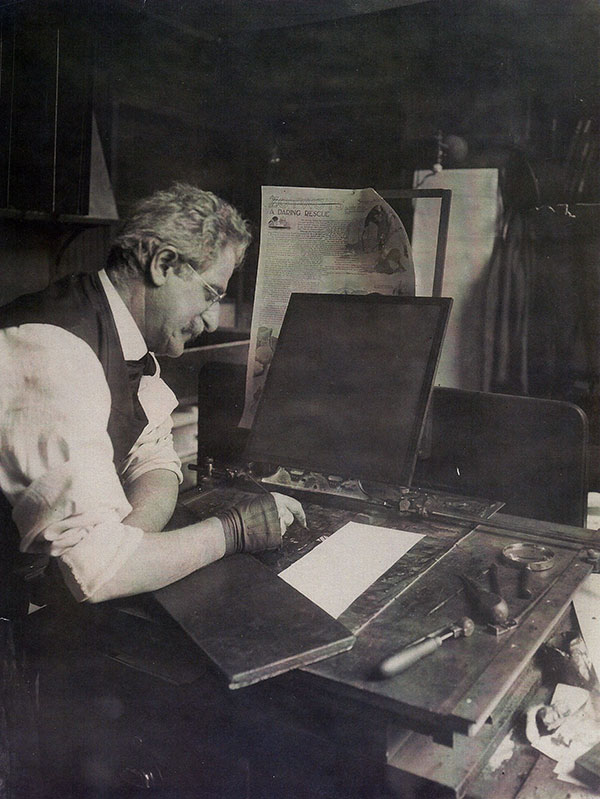

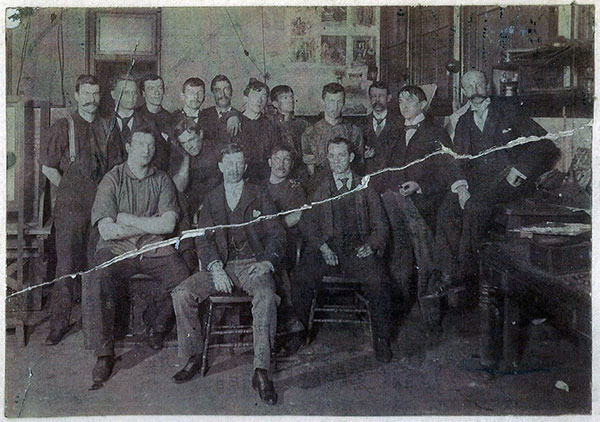

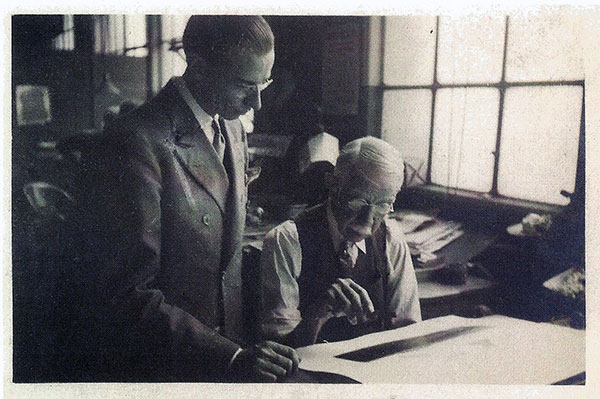

Four colorists appear in as many photographs. Unfortunately, the men pictured are not identified, though their intricate jobs are described in detail and their “high skill” praised:

[The artists in zinc] have to foresee what the effect of the various color combinations will be when the final proof is made, because often four or five different plates are used in the preparation of one color page. The harmony of colors depends much upon the ability of the makers of the plate. The slightest variation in tone may destroy the conception of the artist and produce an effect that would be harsh and coarse. The men of the Herald color department turn out plates of exceptional excellence, and yet rapidly enough to meet every requirement of newspaper speed.

I wondered if Mr. Hunt might be among these four men. Perhaps he was a foreman who collaborated with McCay on color choices for the Nemo strip. Pity, I thought, not to know something, anything, about his job, background and personal life. I feared he and his co-workers, who participated in creating such beautiful graphic imagery, would remain as anonymous to history as the artisans of ancient Egyptian monuments and craftspeople of Chartres.

But — “the gods smile on film historians,” wrote animation historian and author Donald Crafton in his seminal book, Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898 – 1928. Or, as Tennessee Williams put it, “Sometimes – there’s God – so quickly.”

In late November, 2011, I was surprised by an email from Carmen and Jennifer Armstrong, two sisters who knew of my McCay biography. They wanted advice on the value of a collection of color proofs on tear sheets from the New York Herald newspaper’s Sunday color comics, a family legacy from their great-grandfather — Mr. Alfred B. Hunt.

“[He] was a colorist (I think they called them),” Carmen Armstrong wrote. “For the Herald in NYC. He did the coloring for the Little Nemo in Slumberland and other comics. He saved every proof that he did at that time. They are the size of a full page of the NY Times.”

Thanks to the generosity of the sisters Armstrong, I learned a great deal about the formerly mysterious Mr. Hunt when I visited their Long Island home that December, as well as the identity of two of his colleagues on the Ben Day process, depicted in the 1911 Herald story: Al Heatherington and Louis Kreamer, Sr. :

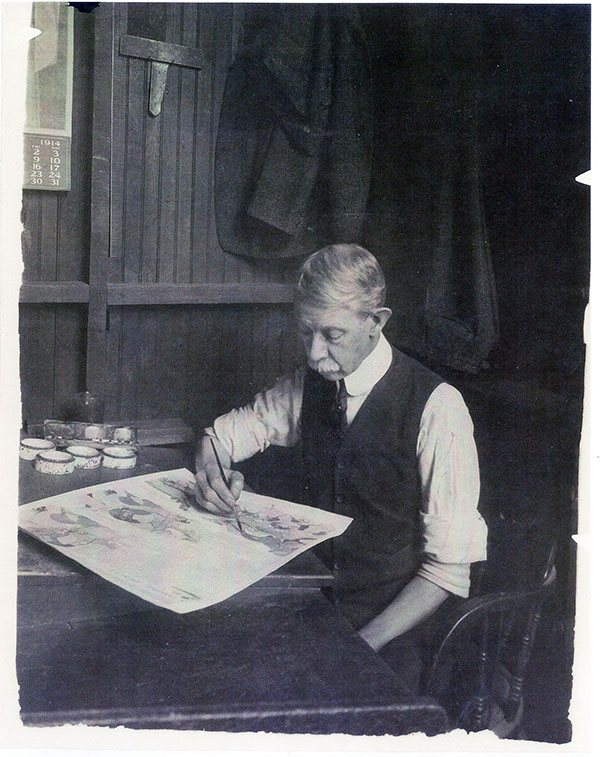

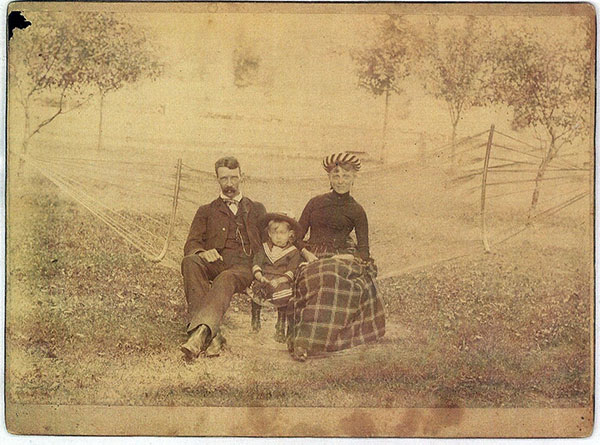

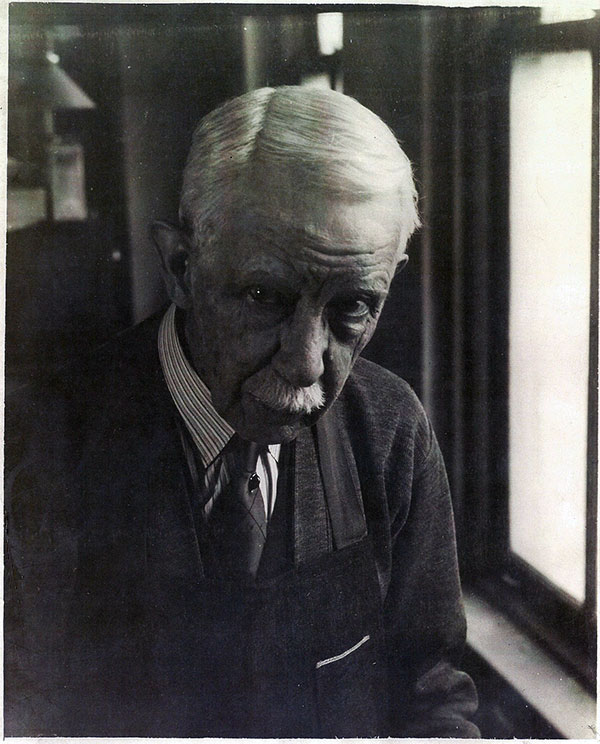

Alfred Benjamin Hunt was born in 1854 on Clarkson Street, Brooklyn, the son of Benjamin Hunt and Hannah Flower Hunt, both natives of England.

When Hunt was three, the family moved to Brookside Avenue, Freeport, Long Island, where his father operated a nearby farm. During the Civil War, the Hunt family lived in Freeport, where young Hunt attended school in Roosevelt. When he was a youth, the family moved back to Brooklyn. Hunt was a graduate of the Academy of Design at Cooper Union, New York City, and began his career working in the printing industry.

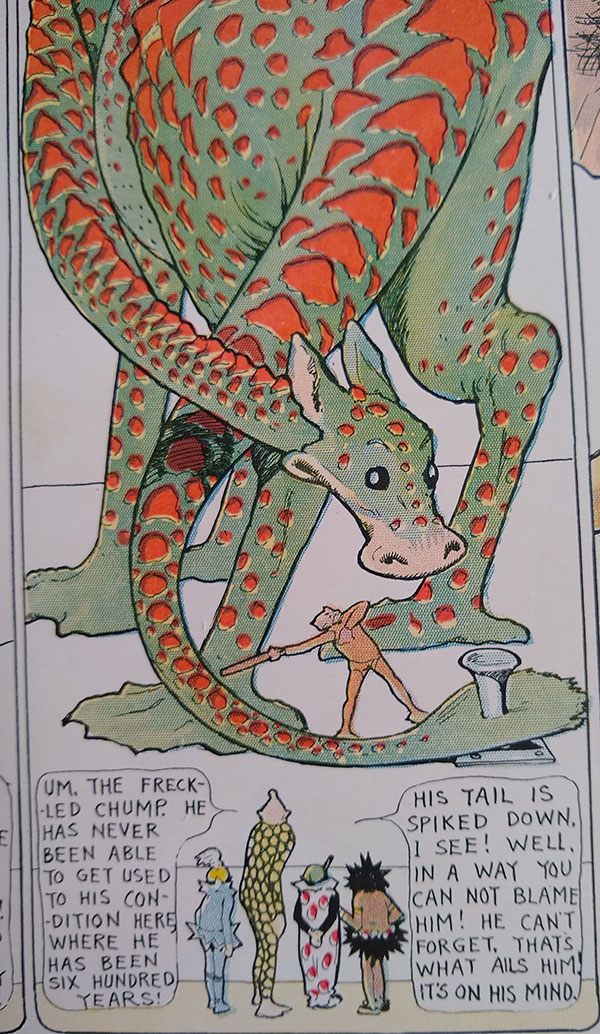

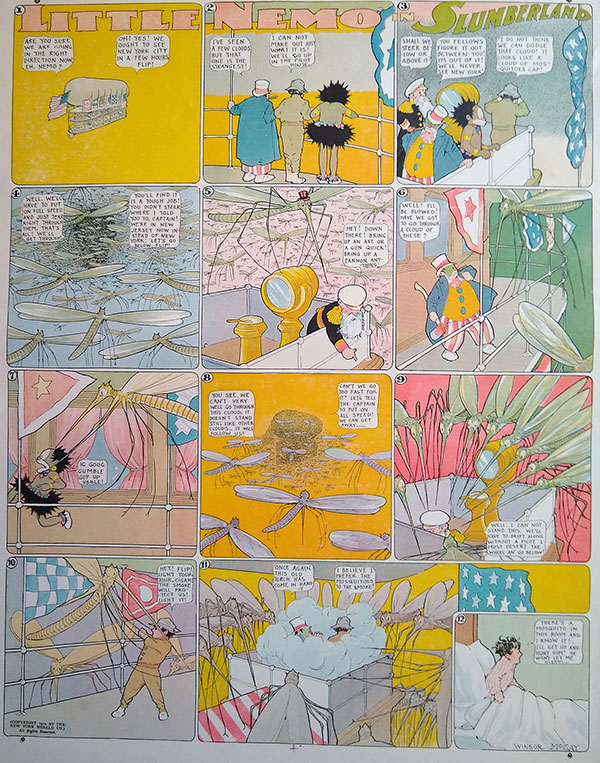

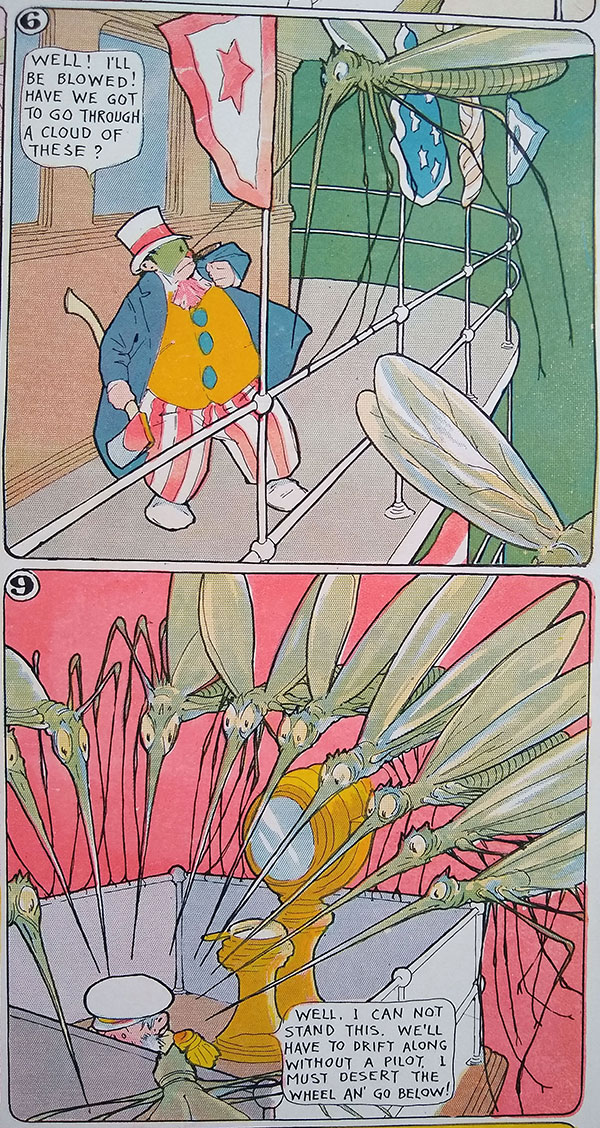

Alfred B. Hunt indeed worked directly with Winsor McCay on the magnificent Little Nemo in Slumberland series, from its beginning in October 1905 (Hunt was then age 51 and McCay age 38) until McCay joined Hearst’s papers in June 1911.

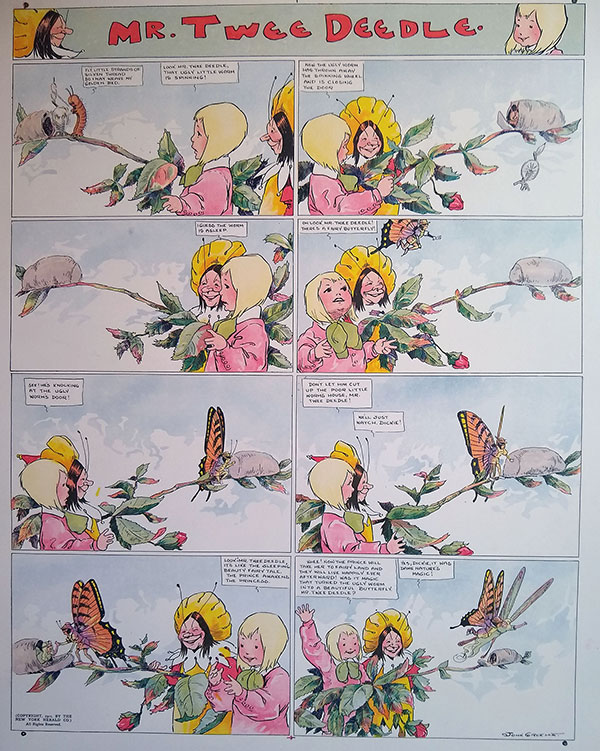

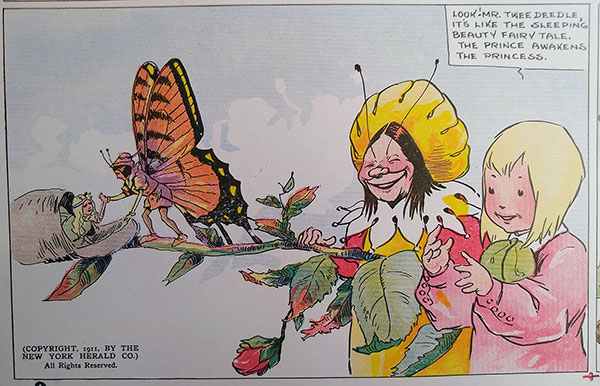

Hunt also supervised color choices and processes for Johnny Gruelle (1880 – 1938) and his Sunday comic fantasy strip, Mr. Twee Deedle, about a magical wood sprite who befriends two human children. The beautifully drawn whimsy, which dips into surrealism on occasion, was the winning entry in a 1910 New York Herald contest that sought a replacement for Little Nemo, when McCay left for Hearst.

Mr. Twee Deedle ran for four years from 1911 to 1914, until it was abruptly discontinued by a new Sunday editor. The Herald publisher, James Gordon Bennett, noticed the omission while traveling in Europe.

“What became of Twee Deedle? cabled Bennett.

“Discontinued by Sunday editor,” was cabled back.

“Discontinue Sunday editor,” was Bennett’s succinct reply.

Mr. Twee Deedle lived another four years.

In 1918, Johnny Gruelle created beloved Raggedy Ann, whose stories, and those of her brother Raggedy Andy, quickly became a publishing and merchandising bonanza for the cartoonist.

A Bonham’s catalogue, for a December 11, 2013 sale of Mr. Hunt’s collection of Herald color proofs, described Mr. Hunt’s work: “After the illustrators brought in their black and white drawings and paintings, Hunt would then apply watercolor to black and white proofs to guide the printers in the final Ben Day color scheme. Among the artists and cartoonists Hunt worked with were Harrison Fisher, Arthur I. Keller, Winsor McCay, Thomas Nast, R. F. Outcault, W. A. Rogers and Dan Smith. Included are many of the Christmas supplements and a large number of the weekly “Fluffy Ruffles” pages written by Carolyn Wells and illustrated by Wallace Morgan.”

After 28 years at the Herald, Hunt left at the time of its merger with the New York Tribune in 1924. He was 70 years old, but then worked at the Boro Engraving Company, Brooklyn, until he finally retired in 1941 at age 86.

Hunt moved back to Freeport in retirement, living at South Long Beach Avenue. His hobby was gardening, laying out and planting vegetable and flower gardens at his home, a continuation of his love of color, this time in three dimensions. Mr. Hunt was the oldest living member of the 23rd regiment of the National Guard, at the rank of sergeant. He was on active duty on many occasions, and received an honorary membership in the Veterans Association of the regiment. He was affiliated with the Williamsburgh Congregational church, Brooklyn, and the Tompkins Avenue Congregational church.

Alfred B. Hunt had only been ill a week when he died on June 23, 1947 at a Rockville Centre convalescent home at age 92.

Carmen and Jennifer Armstrong generously allowed me to copy family photographs, newspaper clippings, and their large collection of original, color-test page proofs, and I am very grateful for their kind support.

These exciting, full-size newspaper pages included over fifty mint-condition Little Nemo in Slumberland color sheets from 1905, 1908, 1909, 1910, and more than 150 full-size color sheets of Johnny Gruelle’s comic strip series Mr. Twee Deedle, among other artists of the period, including an original R. F. Outcault drawing of Buster Brown and his dog, Tige.

I was able to include some of the new biographical information about Alfred B. Hunt in the CRC Press edition of Winsor McCay: His Life and Art, but it was not possible to include photographs or extra artwork.

This post, and the illustrations in the gallery below will, I hope, rectify that omission by filling in some gaps of about the art and skill of Mr. Hunt, a man who participated in the development of a new art form and helped bring into the world enchanting beauty.

Gallery:

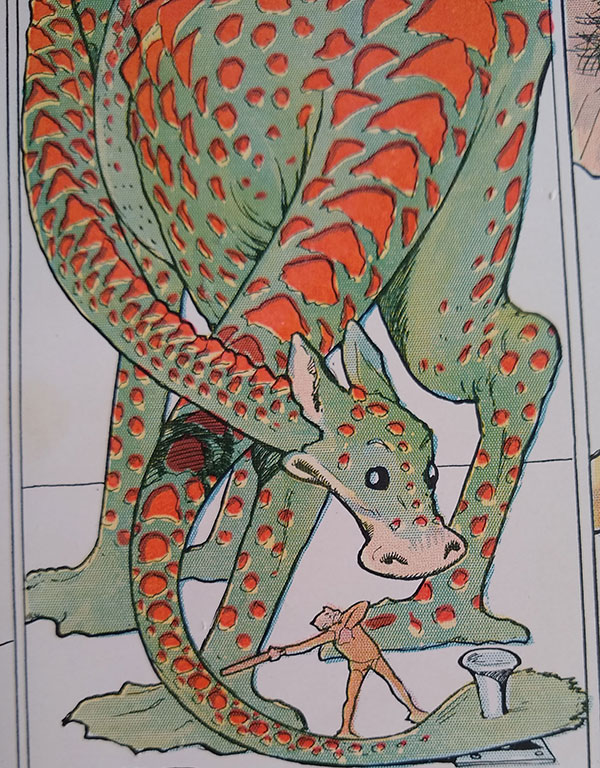

The Little Nemo in Slumberland and Mr. Twee Deedle images here are taken directly from Alfred B. Hunt’s original page proofs, which preserved the vibrant colors of the Ben Day process.

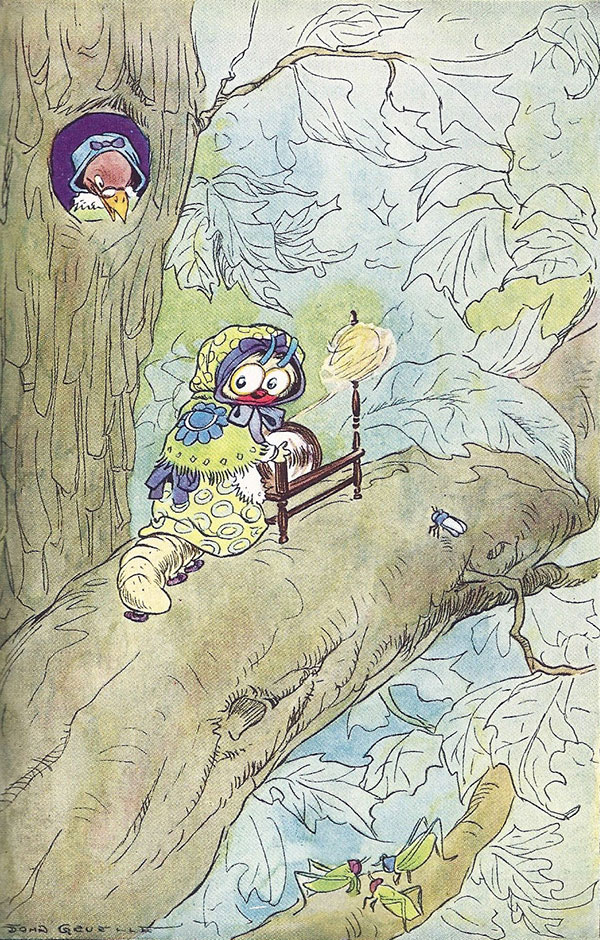

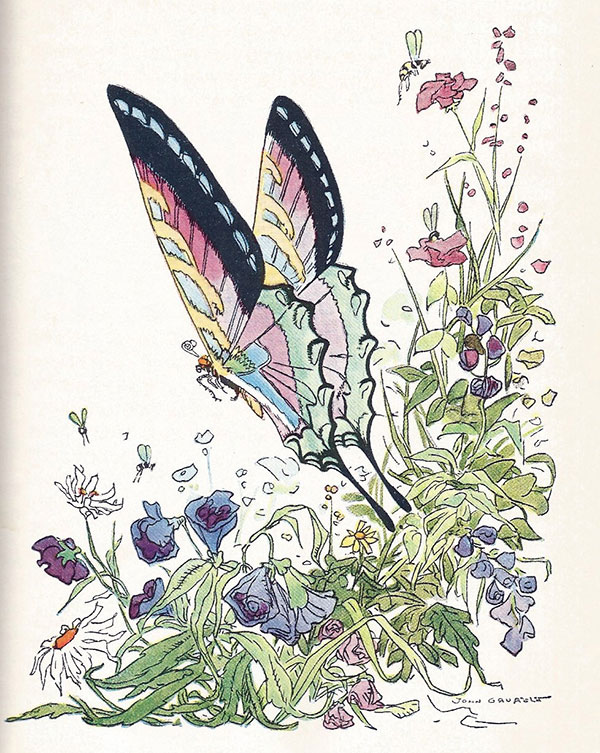

Like many cartoonists, including McCay, Gruelle often re-used ideas; here are two beautiful illustrations from his 1917 book, My Very Own Fairy Stories, telling once again the transformation tale of “The Ugly Caterpillar.”

Information courtesy of:

The Collection of Carmen and Jennifer Armstrong

Nassau Daily Review-Star, 24 June 1947: “Alfred Hunt, 92 Dies; Color Print Pioneer”

Special to the Herald Tribune, Rockville Center, L.I. 23 June 1947 “Alfred B. Hunt”

New York Herald, Mon. 20 April 20, 1914: “Exhibit of Color Print Art Pays Tribute to Work Done by the Herald.”

Addendum

Bonhams – 11 Dec 2013 auction of Alfred B. Hunt collection:

Winsor Zenas McCay (1867-1934). Little Nemo in Slumberland.

59 Color Printer’s proofs Sunday “Comic Section.” The New York Herald 1905-08 sold for US$ 5,250. inc. premium.

Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, pen and ink on illustration board, final panel signed “Silas” (pseudonym for McCay).

Full-page cartoon for the “Comic Section,” The New York Herald, April 27, 1913. A pride of lions fight over a captured man.

Sold for US$ 10,000 inc. premium

Johnny Gruelle (1880-1938). Mr. Twee Deedle.

196 color printer’s proofs Sunday “Comic Section,” The New York Herald 1911-1914 sold for US$ 2,000 inc. premium.

Bonhams – 09 Aug 2016 (The Summer Sale):

Richard Felton Outcault (1863-1928).

“A Bad Cat,” pen and ink on Bristol board. Half-page cartoon for “Comic Section,” The New York Herald . Sold for US$ 62 inc. premium.

Richard Felton Outcault (1863-1928). “The girl, a dog, and her mother’s hat.” Sold for US$ 1,750 inc. premium.

Richard Felton Outcault (1863-1928). “Buster Brown,” pen and ink on Bristol board. US$ 4,750 inc. premium.

Richard Felton Outcault (1863-1928) “Buster Brown and Tige.” US$ 4,375 inc. premium.

Richard Felton Outcault (1863-1928) “Buster Brown in Mischief Again.” US$ 3,500 inc. premium.

Hits: 4033