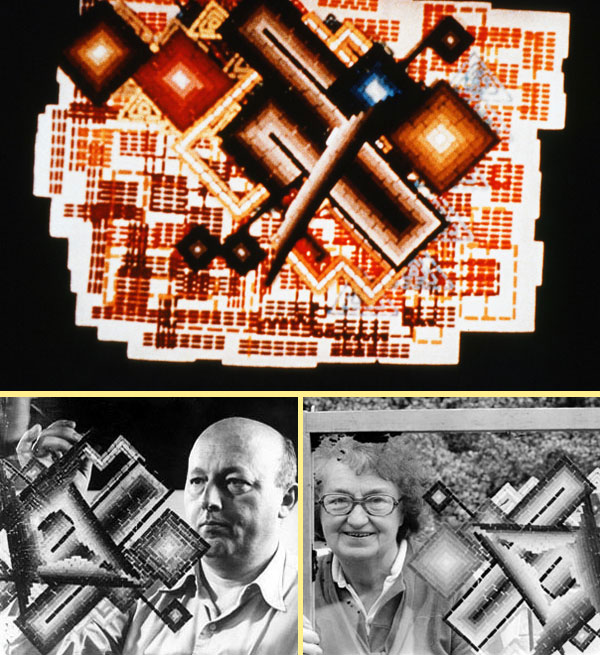

On June 22, an elegant, imaginative, interactive Google Doodle celebrated the 117th birthday of Oskar Fischinger (1900 – 1967), the great visual music/abstract animation film pioneer. Visitors to the Doodle homepage were invited to create both music and accompany it with non-objective imagery — a visceral, tactile homage to Fischinger, “the Kandinsky of cinema.” You can try it here:

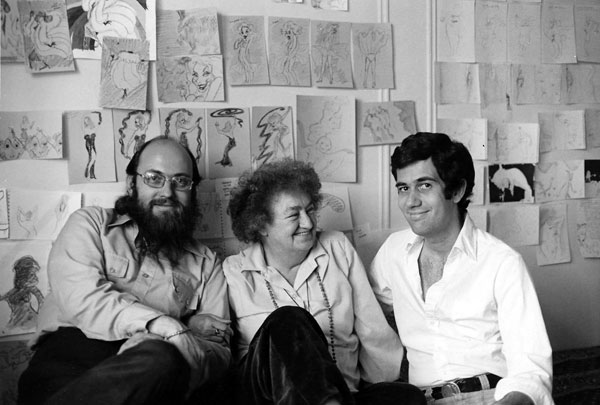

It was very gratifying to me, to see a new generation discovering Fischinger and his enchanting, hand-drawn, pre-digital moving art. I was a close friend, over the course of three decades, of his widow, Elfriede Fischinger (1910-1999) and her associate, Dr. William Moritz (1941-2004), film historian and Fischinger’s biographer.

For years, Elfriede and Bill traveled the world screening Oskar’s films and curating exhibitions of his paintings, keeping his name and reputation alive. I met Elfriede and Bill at the 1976 Ottawa Animation Festival and wrote a candid and affectionate article about them, their adventures and our friendship in the Summer 1978 issue of Funnyworld, Michael Barrier’s brilliant and long-lamented magazine.

In 1977, I was the on-camera host of a CBS Camera Three program, “The Art of Oskar Fischinger,” the first national exploration of his life and work. On the show, I interviewed Mrs. Fischinger and Dr. Moritz.

How thrilled Elfriede and Bill would be to see the Google Doodle; Angie Fischinger, youngest of Oskar and Elfriede’s five children, wrote a touching tribute to her father, noting “It’s impossible to deny true talent, and so it stands the test of time and will continue to do so.”

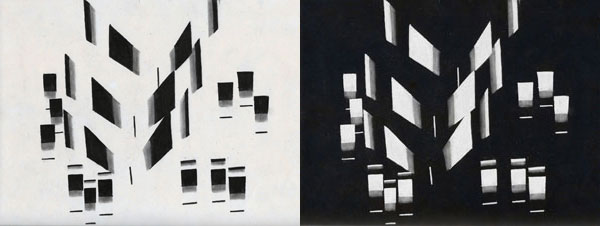

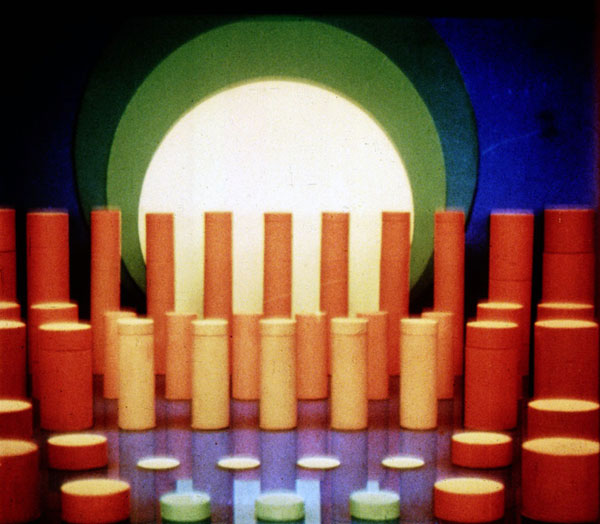

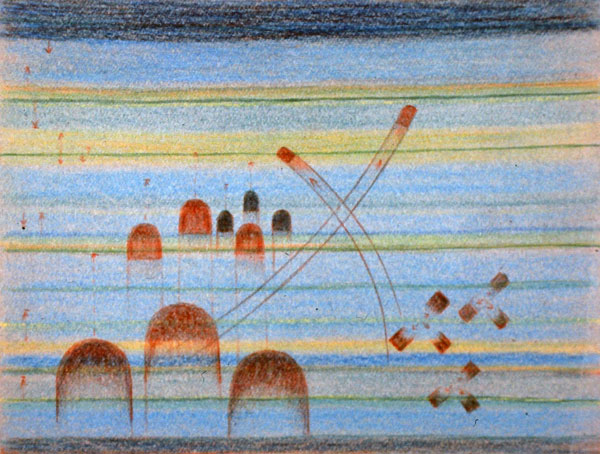

Oskar Fischinger was a fiercely independent, freethinking filmmaker, who began making exquisite film art in the 1920s in Germany. By the 1930s, his fame had grown due to his series of “studies”: geometric shapes and patterns synchronized tightly to classical music and jazz, first in black and white, later in glorious color.

In America in 1936, he and his family sought refuge from the Nazis, who vilified his prize-winning abstract films as “Entartete Kunst”,or “degenerate art”.

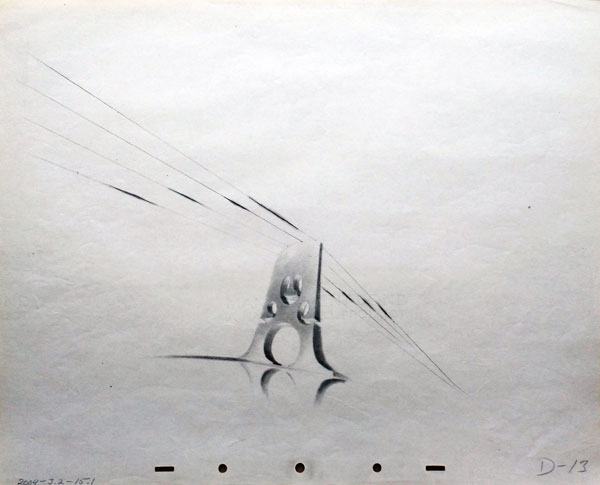

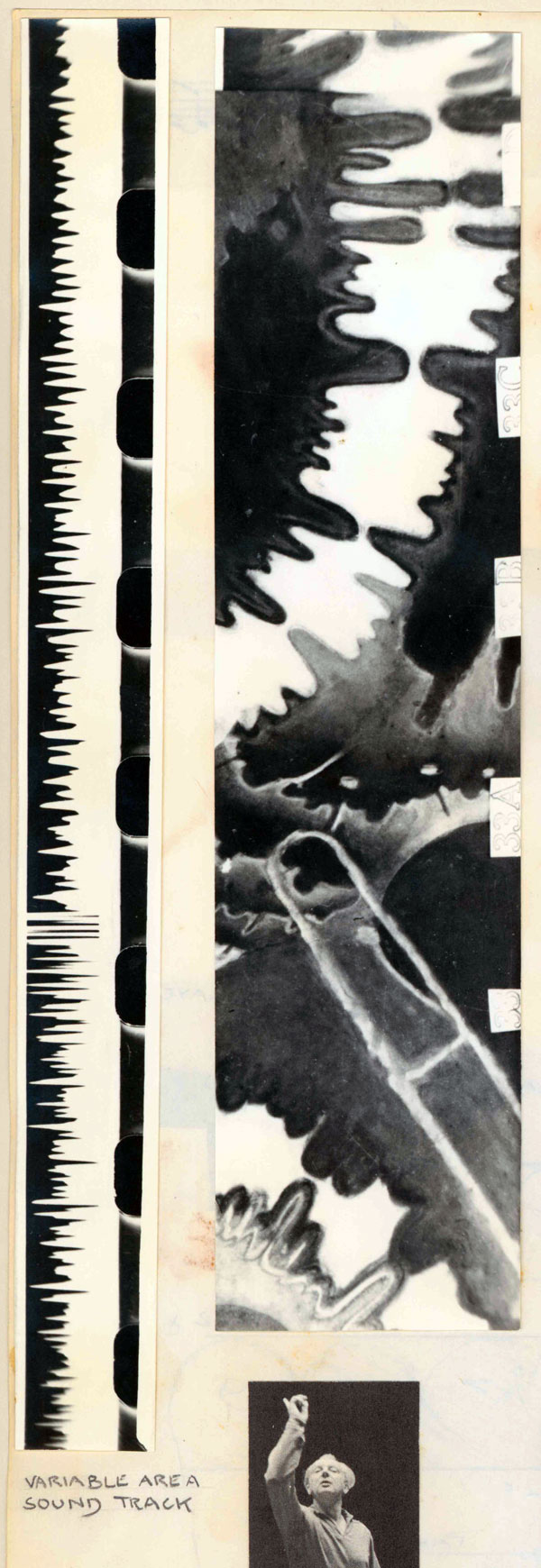

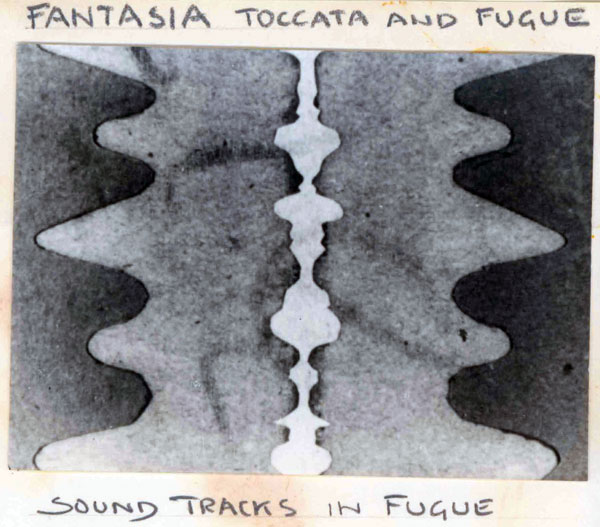

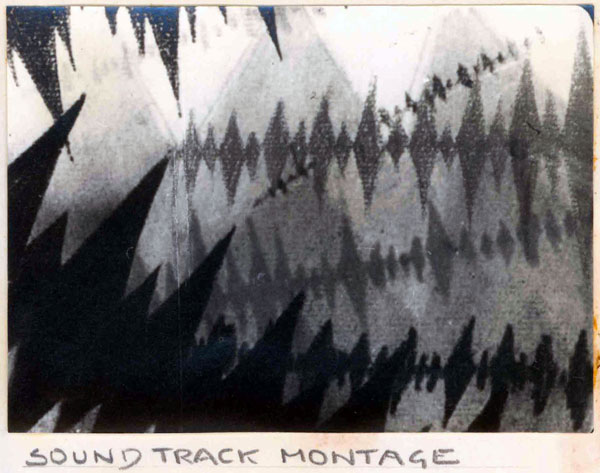

Fischinger found little support for his non-commercial films in this country, and there was virtually no market for the theatrical advertising films that had sustained him in Europe. To survive, he sought employment at commercial Hollywood studios, and worked, always briefly and always unhappily, at Paramount, MGM, and Disney, where his films inspired Fantasia’s semi-abstract “Toccata and Fugue” section.

Fischinger was frustrated by the American studio system, where his distinctive personal vision was subject to modification and adaptation by production teams.

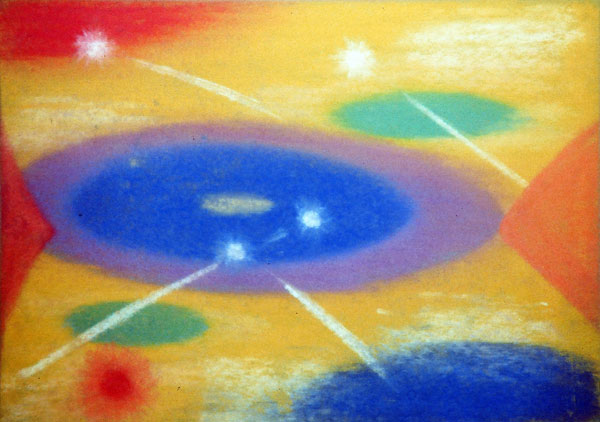

With the help of small grants from the Solomon R. Guggenheim foundation, Fischinger continued creating short non-objective films, completing his last in 1947: the mesmerizing Motion Painting No. 1. His final twenty years were spent painting stunning abstract canvases.

Fischinger’s artworks, both filmed and painted, have inspired generations of artists, including John Cage, Norman McLaren, Orson Welles, Len Lye, Hy Hirsh, Jules Engel, Sara Petty, Larry Cuba, John and James Whitney, Steven Woloshen, Vibeke Sorensen, Harry Smith, Jordan Belson, Edgard Varese, Alexander Alexeieff, Jeff Scher, Mary Ellen Bute, among others.

As I wrote in a New York Times article about “A Fischinger Centennial Celebration” at MoMA in 2000, Fischinger’s films and paintings “easily and joyfully communicate with all sorts of audiences around the world. Far from dry intellectual exercises, his symbols and colors in motion are witty, whimsical, and beautiful as well as profound.”

In addition to the Google Doodle project Fischinger’s film work continues to amaze contemporary audiences around the world, thanks to the diligent efforts of the Center for Visual Music (CVM), under the direction of Cindy Keefer, in Los Angeles. http://www.centerforvisualmusic.org/

The non-profit archive is dedicated to visual music, experimental animation, and abstract media. The CVM online store sells Fischinger DVDs, books, objects and ephemera, and curates Fischinger exhibitions and screenings around the world.

You can view excerpts from Fischinger’s films (and see complete films on demand) here.

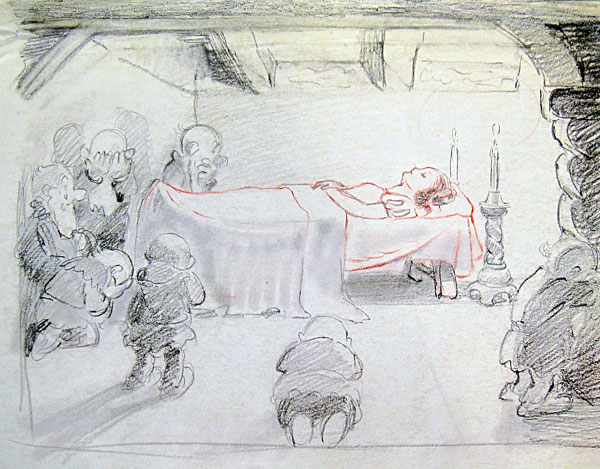

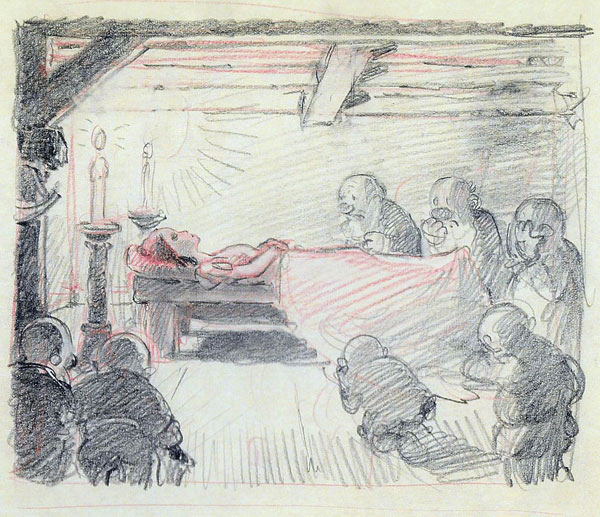

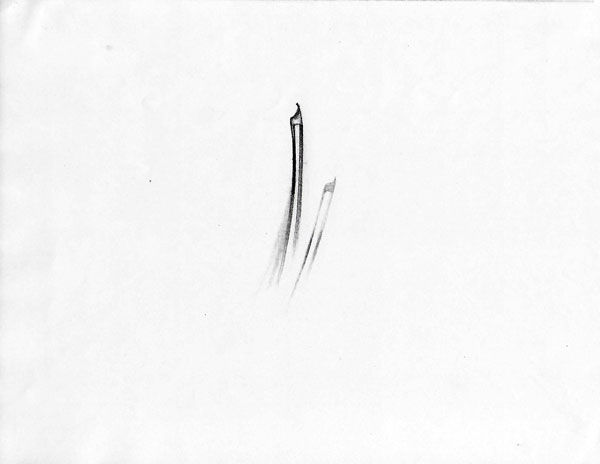

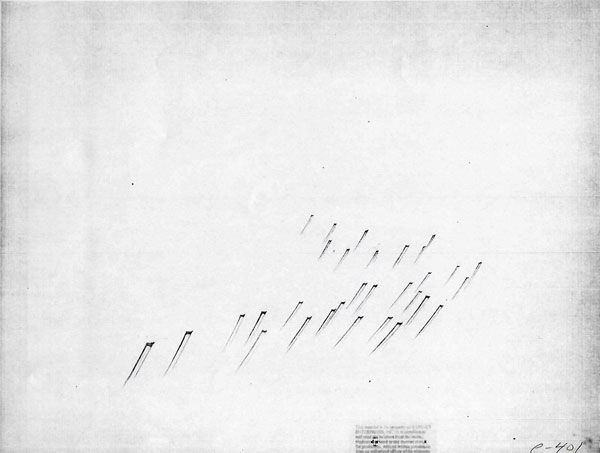

Last fall, for instance, CVM loaned its 2012 reconstruction of Raumlichtkunst (1926/2012), Fischinger’s 1920s multiple-projector work, to the Whitney Museum of American Art’s vast exhibition, Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905-2016. The huge triptych was presented as an HD three-channel installation; elsewhere in the exhibition, CVM also showcased five Fantasia concept drawings by Fischinger from the CVM collection.

William Moritz was a co-founder of CVM, and his archives form an important part of the Center’s research collection. Bill died in 2005, at age 63, after a long battle with cancer. His last years were spent completing his long-awaited biography of Oskar Fischinger, Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fiachinger, which was published just weeks before his death.

William Moritz was a co-founder of CVM, and his archives form an important part of the Center’s research collection. Bill died in 2005, at age 63, after a long battle with cancer. His last years were spent completing his long-awaited biography of Oskar Fischinger, Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fiachinger, which was published just weeks before his death.

Until her own peaceful death in May 1999, a few months shy of her 89th birthday, Elfriede Fischinger continued to restore her husband’s films, promote them, and present them at international screenings. She remained a vital link and witness to the European film avant-garde of the 1920s and 30s. It was my pleasure to know her and work with her, and just to be with her on numerous occasions through the years.

She never changed, I am pleased to say. Her enthusiasms, passion, sense of fun, vibrant personality, and overwhelming childlike energy remained the same, even as her frizzy hair turned from wren brown to snow white.

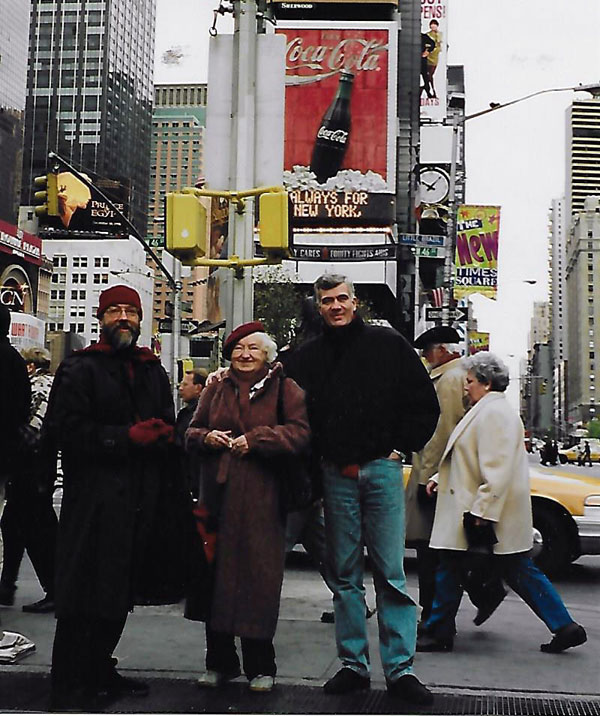

The last time we were together was in New York in November 1998, a few months before she died. She and Bill Moritz appeared as the star attractions of Anthology Film Archives’ First Light festival of abstract films. Because of Anthology’s ever-precarious finances, Elfriede and Bill agreed to third-rate hotel accommodations, a second-rate airline, and a tiny honorarium, offering it all up for the greater glory of Oskar.

That final visit left me with a memorable image of Elfriede. I can still see her standing joyfully smiling in Times Square as electric neon lights flashed on and off, whirled, zigzagged, twisted in space, exploded and burned with colors that would embarrass a rainbow; and as rows of blurred human forms crossed streets, dashed dynamically through the concrete corridors, twisted, turned and nearly colliding with each other and Elfriede. She beamed through it all, standing solidly at the center of a real-life three-dimensional Fischinger canvas: a gigantic Kreise, a cosmic Optical Poem, an Allegretto without limits, an eternal Motion Painting.

It was a beautiful and unforgettable sight. As she used to say when referring to the ultimate of any and every thing: “It vas IT!”

Hits: 5566

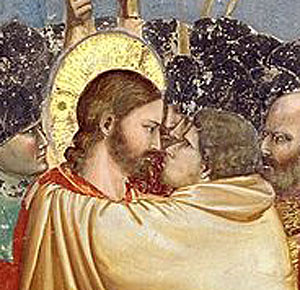

Jesus’ expression is calm, compassionate, forgiving, as he gazes directly into Judas’ eyes. His betrayer, by contrast, shorter or lower in position, appears to be frozen with guilt. His eyes sink into his furrowed, simian-like brow; his lips are still puckered. He is locked in fear and self-loathing. Amidst noisy turmoil, the stare between the two men is quiet; a surreal, slo-mo, time-stopping moment of private thoughts.

Jesus’ expression is calm, compassionate, forgiving, as he gazes directly into Judas’ eyes. His betrayer, by contrast, shorter or lower in position, appears to be frozen with guilt. His eyes sink into his furrowed, simian-like brow; his lips are still puckered. He is locked in fear and self-loathing. Amidst noisy turmoil, the stare between the two men is quiet; a surreal, slo-mo, time-stopping moment of private thoughts.

For on-screen horror, few blood-and-guts film scenes can compete with Giotto’s shocking fresco of the Slaughter of the Innocents: babies torn from their agonized mother’s arms are slaughtered by King Herod’s goons, amid a pile of massacred children.

For on-screen horror, few blood-and-guts film scenes can compete with Giotto’s shocking fresco of the Slaughter of the Innocents: babies torn from their agonized mother’s arms are slaughtered by King Herod’s goons, amid a pile of massacred children. Giotto also possessed a sense of humor and wasn’t shy of displaying comic relief in otherwise serious contexts. Observe the scene-stealing, braying camel that startles its handler in the “Adoration of the Magi” fresco.

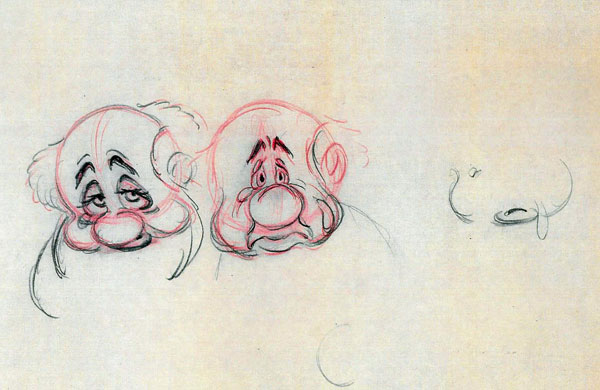

Giotto also possessed a sense of humor and wasn’t shy of displaying comic relief in otherwise serious contexts. Observe the scene-stealing, braying camel that startles its handler in the “Adoration of the Magi” fresco. An excellent draftsman, Hurter (1883-1942) arrived at the Disney studio in 1931 at age 48 with an extensive background in fine arts training and study in Europe. With his encyclopedic knowledge of art history, he often regaled his cartoonist colleagues with descriptions of the art of Vincent Van Gogh, Herman Vogel, Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, Franz Stuck, and Heinrich Kley, among others.

An excellent draftsman, Hurter (1883-1942) arrived at the Disney studio in 1931 at age 48 with an extensive background in fine arts training and study in Europe. With his encyclopedic knowledge of art history, he often regaled his cartoonist colleagues with descriptions of the art of Vincent Van Gogh, Herman Vogel, Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, Franz Stuck, and Heinrich Kley, among others.