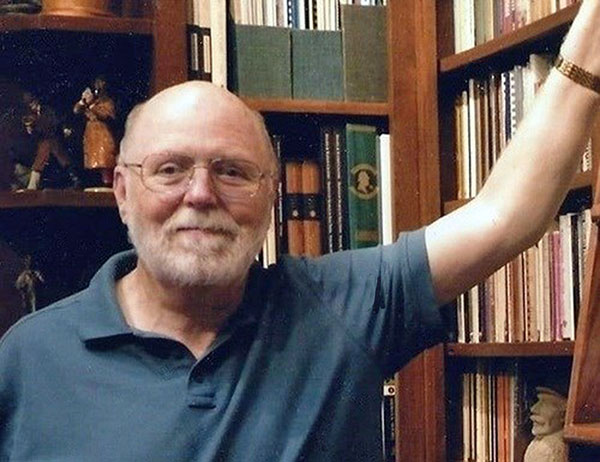

Russell Merritt (1941-2023) was a brilliant man of parts, a knowledgeable, articulate scholar whose lasting accomplishments in film history research, writing and teaching originated in his insatiable appetite for lifelong learning. He inspired students and readers internationally with his intelligent, witty lectures, films, books and periodicals, all delivered with a signature brio. We, who were lucky enough to enjoy a personal friendship with Russell and his wife Karen, were shocked and deeply saddened by his untimely death in March 2023.

Russell Merritt (1941-2023) was a brilliant man of parts, a knowledgeable, articulate scholar whose lasting accomplishments in film history research, writing and teaching originated in his insatiable appetite for lifelong learning. He inspired students and readers internationally with his intelligent, witty lectures, films, books and periodicals, all delivered with a signature brio. We, who were lucky enough to enjoy a personal friendship with Russell and his wife Karen, were shocked and deeply saddened by his untimely death in March 2023.

Russell Merritt was born in 1941 and grew up in New Jersey and Connecticut. In a bow toward self-education, he often skipped school to join his young friends in attending Broadway shows and movies (both contemporary and historic films) in New York City. Other of his early interests was a passion for Sherlock Holmes mystery stories. At age 16, precocious Russell became the youngest member of the ultimate Holmes society, the Baker Street Irregulars.

His formal higher education was equally impressive, including attendances at Boston University and Northwestern University, and Harvard, where he received a Ph.D in English in 1970 with a dissertation on D.W. Griffith’s films. Years later, he became a senior adviser to Kevin Brownlow and David Gill on the American Masters three-part Emmy-Award nominated television series, D.W. Griffith: Father of Film.

In 1968, Russell began his pedagogical career at University of Wisconsin, where he started a film studies program and directed the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theatre Research, which attracted numerous film and television collections. He soon rose to full professor status with an ever-widening resume of lectures on film and related topics.

In 1970, he and his beloved Karen Maxwell began their 52-years of married life. They were well-matched: she is also a prolific writer, lecturer and teacher, on topics including Women’s Studies, Higher Education, as well as cinema. 1 She has also held academic administrative and consultancy positions in Wisconsin and California, and, until her retirement in 2006, was Director of Academic Planning at UC Merced.

When the couple moved to Northern California in 1986, Russell taught film courses at UC Berkeley, Stanford University and San Francisco State, while adding to his research publications; for example, his impressive essay, “Recharging Alexander Nevsky: Tracking the Eisenstein-Prokofiev War Horse” (Film Quarterly, Winter, 1994-1995. Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 34-47). Russell’s detailed explanation of how Eisenstein and Prokofiev studied Disney’s Snow White and the recording techniques of Fantasia when creating Alexander Nevsky is a high achievement of deeply researched, cogent writing about the making of Eisenstein’s 1938 historical drama film.

Russell also enjoyed contributing valuable programming and lectures to UC Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archive, and was active in the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF). He was especially proud of his close affiliation with the San Francisco Silent Film Festival (he became a member of the Festival board in 2014) and Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy.

The latter festival, in 1992, published the first of two scholarly, entertaining, beautifully illustrated animation history books, co-authored by Russell Merritt and his friend, the esteemed Disney animation/American silent film scholar J.B. Kaufman. Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney — a bilingual edition that was revised in 1993, which I reviewed for the New York Times Book Review. 2

The second book, Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies – A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series, was published in 2006, revised in 2016. In an article (“Lost on Pleasure Island”) in the fall 2005 issue of Film Quarterly, Russell Merritt previewed the Silly Symphonies book in a detailed essay about the film series’ powerful storytelling techniques. The article again showcases Russell’s value as a critical analyzer who digs deep for “another look” at film classics; in this case, “the psychological underpinning of . . . Disney’s unsettling power [which] comes from his ability to explore the inner life of the child.”

Russell received two lifetime achievement awards in 2018: Le Giornate del Cinema Muto’s Jean Mitry Award for his work in restoring and celebrating silent film history; and a special recognition from the Denver Silent Film Festival, when Russell became the first David Shepard Career Achievement recipient for his collaboration in several silent film restorations, such as the 1916 William Gillette film Sherlock Holmes and the Polish Film Archive and San Francisco Silent Film Festival restoration of Der Hund von Baskerville.

On a personal level, I and my husband Joseph Kennedy enjoyed the great pleasure of many happy times in various locales spent in the delightful company of Russell and Karen Merritt.

One time, after attending the Cinema Muto festival in Podernone, we four traveled to the Merritts’ favorite city, Venice, where they gave Joe and me a personal tour of the city’s grandest sights and delicious restaurants. For, among their many talents, Russ and Karen were connoisseurs of fine food who shared gourmet feasts with us during their annual Manhattan visit (at, for example, Le Bernardin), or when we were in San Francisco (the legendary La Folie). Through the years, he and Karen often attended my lectures and exhibitions at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco and the Pacific Film Archive.

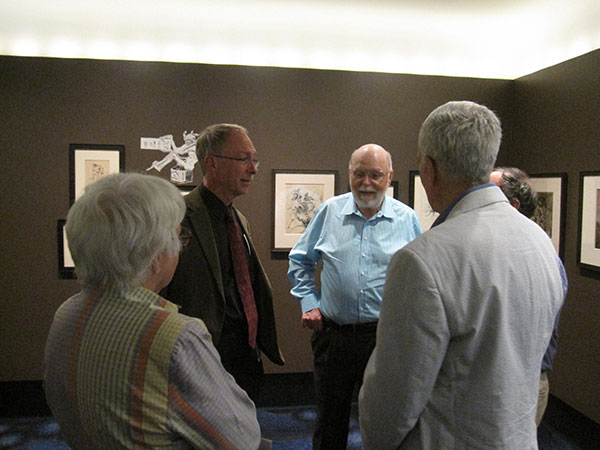

at the Walt Disney Family Museum, 2012

In his spare time, Russell was an eager volunteer in the San Francisco City Guides, often leading tourist walking tours through the historic Castro district and the famed Castro Theatre. When Russ and Karen came east, Joe often reciprocated by offering a knowledgeable tour of Manhattan’s historic parts; such as the Five Points, the infamous 19th century slum, now part of Chinatown, showcased in Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film, Gangs of New York.

Through the years, Russell and I enjoyed lively email and telephone conversations. In our last communication online, we discussed his thoughts about two museum exhibitions Joe and I encouraged them to see during their brief New York visit in early January of this year.

Russell was enthusiastic about the puppet production art and props displayed at MoMA’s Guillermo del Toro: Crafting Pinocchio. It inspired him, upon return to California, to study the stop motion film in detail on Netflix. “I had a fine time the other day watching [del Toro’s] Pinocchio without sound,” he wrote. “The great surprise: how important lighting was to creating atmosphere.”

The other highlight during their last visit, was the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s two exhibitions of Mayan and Tudor Art [Lives of the Gods: Divinity in Maya Art; and The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England]. Russell reported:

I kept flinching at the complexity of the Mayan treatment of animals and gods — how can I live long enough to explore all this adequately?

The Tudors, on the other hand, brought me back home. The tapestries in particular were a call to my grad student days as an English major. More wallowing: this time in all those historical and mythological allusions and all that opulence. We usually skip over Henry VII to study his kids. But dad knew a good Flemish tapestry when he saw one, and was a trend setter in finding those Dutch painters to paint his phiz [physiognomy]. 3

In these two brief observations by Russell Merritt, one can see the joy he always took in learning, analyzing, and making his discoveries interesting to his audience, even if it was one person. He was a master communicator. Particularly enjoyable is the direct way he made his views and connections so personal and such fun to hear – especially his freewheeling humorous word usage. No wonder his students loved him. He shared so much knowledge and positive energy with them.

“Hearing your voice over the phone made me so happy,” said one of Russell’s former students, now teaching middle school in Brooklyn, in a February 22, 2023 note he proudly shared with me. “Inspired by your positive experience with MoMA’s Pinocchio exhibit, I went there yesterday and enjoyed every minute of it . . . This exhibit has motivated me to sign up for a stop motion animation course this fall,” the better to help prepare to bring animation into her classes. Russell told me the note “shows the far-reaching effects of our get together in New York . . . I begin to understand how midwives feel.”4

I phoned him on February 28 and we had a wonderful laughter-filled one-hour talk. He emailed me on March 1: “Here’s hoping this was the first of catch-up calls. It was a lovely treat.” He signed off with “How are you enjoying retirement? I’m still adapting. Love to you both, Russell.” 5

His passing two days later at age 81 was a great shock.

It is a heartbreaking loss to his devoted wife Karen, and his sister, Carole Merritt Nichols; also, to the world of cinema scholarship and education, and his many students and legions of friends around the world. Joe and I are not alone in missing him greatly.

Notes

- “The Little Girl/Little Mother Transformation: The American Evolution of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” by Karen Merritt. Storytelling in Animation, ed. John Canemaker (Hollywood: American Film Institute, 1988). (Published in Italian as “Da bambina a piccola madre: la trasformazione americana di Biancaneve e i sette nani,” Griffithiana, n. 31, December, 1987.)

- John Canemaker, “Walt in Wonderland,” New York Times Book Review, 10 July 1994.

- Email to JC & JK from RM, 12 Jan 2023.

- Email to JC & JK from RM, 28 Feb 2023.

- Email to JC from RM, 1 Mar 2023.

Hits: 208