Frederic Franklin, the great, high-spirited, charismatic, British-born dancer and ballet master, performed from his teens into his 90s, and inspired numerous choreographers to create for him, including Léonide Massine of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, George Balanchine (Danses Concertantes) and Agnes de Mille (Rodeo).

Frederic Franklin, the great, high-spirited, charismatic, British-born dancer and ballet master, performed from his teens into his 90s, and inspired numerous choreographers to create for him, including Léonide Massine of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, George Balanchine (Danses Concertantes) and Agnes de Mille (Rodeo).

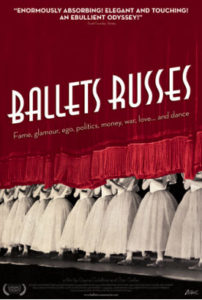

I first encountered him in a film: Ballets Russes (2005), one of the most beautiful and poignant documentaries about dance ever made. It is an intimate portrait of pioneering 20th century dance artists, who were then in their 70s, 80s and 90s, who birthed modern ballet under the Ballet Russe banner.

“Freddie,” as he liked to be called, practically steals the documentary, not only in vintage footage of him as a major star dancer. But also by virtue of his uncannily detailed memories, delivered in juicy anecdotes with authority, wit and candor. Franklin was, as the film’s producer/directors Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine put it, “possibly the most active octogenarian we’d ever encountered and certainly one of the most fabulous raconteurs.”

As an animator, it is a wonderful film to study, not only from a movement analysis viewpoint, but also to observe these brilliant dancers over a wide span of time, from vigorous youth to old age.

Frederic Franklin, born in Liverpool, England in 1914, was among the dance world’s most revered and beloved figures, known for his ebullient can-do personality and extraordinary vitality and versatility. He was a dance pioneer who took on — and dazzled audiences in — a remarkable interpretive range of roles and styles, among them the elegant Prince in Swan Lake, a hoedown-happy cowboy in Rodeo, and loutish Stanley Kowalski in Valarie Bettis’ balletic version of A Streetcar Named Desire.

“Comedy, drama or the intricacies of Balanchine’s neoclassicism — all were at his command,” dance historians Nancy Reynolds and Malcolm McCormick wrote of Franklin in No Fixed Point (2003). Leslie Norton in Frederic Franklin: A Biography of the Ballet Star (2007) described his physical beauty: “This handsome lad had eyes of sapphire blue, golden hair, and a skin of milk and roses . . . altogether the round-cheek English choirboy.” Agnes de Mille called him “the first great male technician I had ever had a chance to work with. And I tried everything I thought the human body could accomplish. He was strong as a mustang, as sudden, as direct and inexhaustible.”

In his later years, Franklin’s sharp memory, and his history of working with great choreographers and dancers, made him an invaluable resource as a teacher and stager of revivals. His phenomenal recall of dance steps, dancers and events past is vividly demonstrated in the Ballet Russe documentary.

I had the pleasure to meet Frederic Franklin in person in 2012, seven years after seeing him on film. (From here on, I’m going to refer to him as “Freddie,” because he said that I could.) My friend Mindy Aloff, the esteemed dance historian/author — whom animators will know from Hippo in a Tutu, her superb 2009 book on dance in Disney animated films — invited me to sit in when Freddie addressed her Barnard College “Dance in Film” seminar students.

Soon after, on June 4, 2012, Mindy, a friend of Freddie’s for many years, arranged for us both to chat with him at his penthouse apartment on West End Avenue on New York’s Upper West Side, where he and his partner, William Haywood Ausman, lived for 45 years.

Soon after, on June 4, 2012, Mindy, a friend of Freddie’s for many years, arranged for us both to chat with him at his penthouse apartment on West End Avenue on New York’s Upper West Side, where he and his partner, William Haywood Ausman, lived for 45 years.

He was 98 years old at the time, but full of energy, warmth and charm. I was in awe of his ability to answer, with sharp recall, inquiries about his fabled career. During a second visit, on August 16, I wisely brought a tape recorder, with Freddie’s permission. For each time, he took us on a personal journey through nearly a century in the dance arts.

He was 98 years old at the time, but full of energy, warmth and charm. I was in awe of his ability to answer, with sharp recall, inquiries about his fabled career. During a second visit, on August 16, I wisely brought a tape recorder, with Freddie’s permission. For each time, he took us on a personal journey through nearly a century in the dance arts.

Dressed in a white cable-knit sweater and slacks, Freddie sat ramrod-straight looking like a grand egret, his long arms and hands making expressive movements abetted by spot-on vocal mimicry. Through his verbal and mimetic gestures, I saw him dancing at age six at his home in Liverpool, listening to a gramophone and jumping around in front of a mirror after seeing a production of Peter Pan.

Dressed in a white cable-knit sweater and slacks, Freddie sat ramrod-straight looking like a grand egret, his long arms and hands making expressive movements abetted by spot-on vocal mimicry. Through his verbal and mimetic gestures, I saw him dancing at age six at his home in Liverpool, listening to a gramophone and jumping around in front of a mirror after seeing a production of Peter Pan.

His first teacher, Marjorie Kelly, ran a local classical ballet school. “Oh god, she was a tough lady, but a very good teacher,” he recalled. “I was terrified of her.” At their first meeting, she commanded, “Young man, do something!” So the tot got up and . . . jumped around. After a brief discussion with his mother, the prescient Mrs. Kelly announced, “I’ll take him. He’s good!”

His first teacher, Marjorie Kelly, ran a local classical ballet school. “Oh god, she was a tough lady, but a very good teacher,” he recalled. “I was terrified of her.” At their first meeting, she commanded, “Young man, do something!” So the tot got up and . . . jumped around. After a brief discussion with his mother, the prescient Mrs. Kelly announced, “I’ll take him. He’s good!”

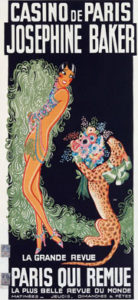

More teachers and training followed through the years. In 1931, jobs in ballet were scarce in England, so 17-year old Freddie began his career as one of ten chorus boys at the Casino de Paris, a large music hall on rue de Clichy.

Under the name The Jackson Boys, they performed in the revue Paris qui Remue with the African-American performer who became an international sensation, Josephine Baker (1906-1975).

“She was a lovely lady and I remember we did a number with her,” he said, and then sang a refrain from two of Baker’s signature songs, La Petite Tonkinoise and J’ai deux amours. The 24-year old Baker had changed her image from her “Danse Sauvage” performances of 1925, in which she performed a frenzied Charleston dressed only in a girdle of bananas. Now she was sleek and polished, still bare-breasted but cloaked in huge ostrich feathers and accompanied on stage by her pet leopard, Chiquita.

“She was chocolate brown and she glistened, and her hair was covered in [here Freddie affected a French accent] Bah-kair Feex [Baker Fix], a kind of pomade for her hair sold in the stores.”

Here is a short film clip (silent) of Josephine Baker performing at the Casino de Paris in 1931 (Freddie does not appear in this clip):

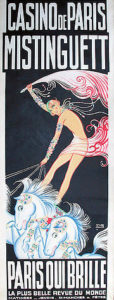

I was curious about Mistinguett (1875-1956), the legendary French performer, who followed Baker’s show at the Casino. Freddie, of course, knew and worked with her, and offered first-hand information.

Though little known today in America, the saucy chanteuse was once the world’s highest paid female entertainer. Jean Cocteau affectionately described her voice as “slightly off-key [like] that of Parisian street hawkers — the husky trailing voice of the Paris people.”

Here is Mistinguett, performing in a 1936 French film at age 60, a few years after Freddie worked with her:

Filling in for an ill performer, teenaged Freddie sang a duet with 56-year old Mistinguett, as she draped her shapely legs across a piano that Freddie was also playing.

“When we worked with her, she was an old lady,” he said of his youthful perspective, but “very, very well-preserved. Very carefully made up. Always knew where the light was. The audience adored her. She was a big, big star. Oh, I was so thrilled.” He then croaked out, à la Mistinguett, the then-popular American song they sang together, “You’re Driving Me Cra-a-a-a-zzzz-eeee.”

The finale of her show, Paris Qui Brille, (“Paris Which Glitters”) was spectacular. On stage, two live horses galloped on a giant treadmill with Mistinguett in a chariot holding the reins. “She wore a lovely helmet and something streaming in the back,” Freddie recalled. “The horses were on rollers and they galloped! And we’re all below [dancing and singing] as she’s leading the horses. I mean it was a sensation!”

In 1935, Franklin joined the Markova-Dolin Ballet in London. Three years later, Massine hired him for a new company, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, where he stayed until it disbanded in the 1950s. There, he was often paired with the exquisite, glamorous Russian, Alexandra Danilova (1903-1997), prima ballerina of Massine’s company. Franklin and Danilova became, wrote dance critic and historian Jack Anderson, “one of the great partnerships of 20th century ballet.”

Their vibrant, sparkling charisma is exemplified in Gaite Parisienne, with Franklin as the ardent Baron and Danilova as the effervescent Glove-Seller. The footage below was made by Victor Jessen, who secretly filmed with a 16mm camera over multiple performances, and edited the takes to an audio recording of an actual performance:

Danilova, who was eleven years older than Franklin, had a career that extended from the Imperial Russian Ballet of St. Petersburg to Sergei Diaghilev’s original Ballet Russe in the 1920s. At their first rehearsal, she told Franklin, “You have to learn where my curves are.” “With Danilova,” said Freddie, “Oooh, I was terrified!” They did become friends, “but it took time.” Eventually, she allowed him to call her by her nickname Choura.

He imitated her rehearsal demands: “‘What happened? Why you not push? Why you not pull?’ I’m pushing and pulling, I hope in the right places! Little by little, she said, ‘You know, you are like young horse. I train you.’ She did. That’s how they talked to you, the Russians.”

During World War II, Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo mostly toured America on grueling schedules for little money; but their dedication to their art brought the magic of classical and avant-garde ballet to hundreds of towns and cities. Whenever they played Hollywood, movies stars swarmed to their performances, even to a Warner Bros. sound stage where, in 1941, the ballet dancers shot three Technicolor featurettes: The Gay Parisian (1942); Spanish Fiesta (1942); The Blue Danube (never released). Freddie befriended many of the stars, especially Ginger Rogers, famed as Fred Astaire’s dance partner.

“Freddie, I think The Ginger, she is here!” Choura whispered during a break filming Spanish Fiesta when Rogers was seated near the camera, the better to observe the ballet dancers. “We go. We go to The Ginger,” said Choura, as they were beckoned for introductions to the movie star. Some evenings, at the theatre where the Ballet Russe was performing, Rogers sat off-stage, observing. After Freddie’s performance, they’d dash to her limo. At her home, Leila Rogers, her mother, cooked them supper. “We were pals,” Freddie said of Ginger. “But she wanted so much to be a [classical] dancer. She’d get up and show me things. And I’d say, ‘No, Ginger, not like that. Let your arms go. We had a really good time.”

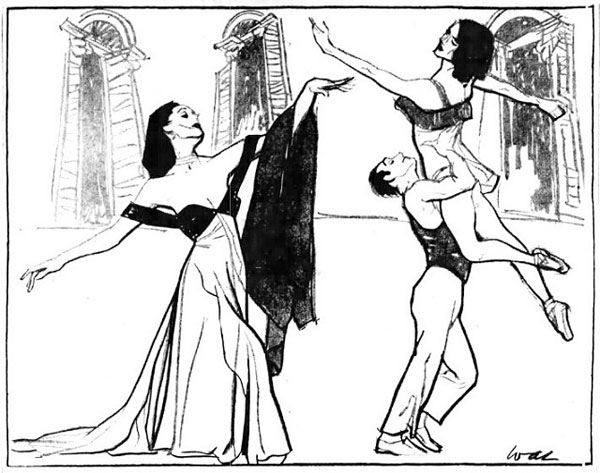

After ceaseless financial troubles caused the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo to briefly disband, Freddie formed his own company in 1950 with ballerina Mia Slavenska (1916-2002). (He rejoined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1954, staying until 1957.) One of the most daring pieces in the Slavenska-Franklin Company’s repertory was an adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire choreographed by Valerie Bettis (1919-1982), with the sensuous Slavenska as Blanche DuBois, Lois Ellyn as Stella, and Franklin as Stanley. “Mia was in ecstasy,” he said. “‘Oh, it’s wonderful for me,’ she said. ‘Just right!’”

Freddie, however, worried about his ability to do justice to the role made famous on stage and screen by Marlon Brando. The distance emotionally and physically from an elegant, dashing noble in Gaite Parisienne to Stanley Kowalski, a brute in a wife-beater tee shirt “was a big thing,” he recalled thinking. “Because everybody said, ‘Franklin? Nev-vah!’”

Bettis disagreed. She believed there were dark depths and strengths within Freddie that had never been brought forth before. “If you’ll do everything I ask you,” she bargained with the dancer, “I will go inside and I will take something out. We can make this work. Just do.” To which Freddie replied, “Valerie, I’m wide open.”

When the ballet opened in New York on December 8, 1952, Frederic Franklin’s performance as Stanley “startled the ballet world” because, wrote his biographer, Leslie Norton: “A sensitive and endearing personality, long noted for his boyish charm, Franklin left behind his engaging ways to create a brutal, loutish character.”

Influential contemporary dance critics attested to the success of the Bettis/Franklin collaboration. John Martin wrote of Freddie’s “tremendous force” in the role:

As Stanley, Mr. Franklin gives the performance of his life . . .

When the angry Stanley chases the hapless Blanche through

a series of shuttered doors . . . it delivers a wallop that you are

not likely to forget.

Walter Terry wrote of his performance:

. . . the most telling characterization in his illustrious career . . .

He dominated the ballet throughout. Never was there a false

gesture, never a moment when conviction seemed lacking.

Alexandra Danilova, after attending a performance, asked, “Freddie, what they do with you? Is new. Is just new. Perfect. Wonderful!” Perhaps the greatest compliment came from Marlon Brando. In a note, he wrote that he wished he could have done with his voice in Streetcar what Freddie did with his body.

Little more than an hour passed during our time conversing, but, thanks to Freddie’s wonderful memory and precise descriptions, so had decades of a special artist’s life lived to it’s fullest. Years of dancing with joy, zest and consummate skill, despite a vagabond life of long train journeys and one-night stands in theatres large and small, shabby and grand. Audiences adored him, and their imaginations and lives were enriched by the repertoire and productions he starred in.

In later years, Freddie focused on coaching and directing, launched the National Ballet in Washington, created and staged dances for Dance Theatre of Harlem and Chicago’s Joffrey Ballet, among other venues. In 2004, Queen Elizabeth II invested Frederic Franklin as Commander of the British Empire. He never fully retired from the stage. In his 90s, his remarkable vitality intact, Freddie continued to dance character and pantomime roles in American Ballet Theatre productions.

“Oh, there’s been the ups and downs like everyone,” he told me. “But I’ve been fortunate. I’ve met and been around lovely people. And, of course, there have been some . . . [pause, grimace] . . . other people and difficult moments. There was one moment I woke up and I didn’t have any money. It had all gone. So, up by the bootstraps, once again!

“So it’s been a wonderful life. It has. And I’m very, very grateful for all of it.”

Soon after my last meeting with Frederic Franklin, I wished I could see for myself how that genial gentleman morphed into monstrous, brutish Stanley. As an animation teacher, I often suggest that students invest personality into characters basically through the way they move, like the great silent film actors and clowns did.

Fortunately, New York’s Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts, has two black-and-white videos in its collection: bits and pieces of a few scenes shot on film by Ann Barzel of the original 1952 Bettis ballet; and a quick demonstration in 1959 by Franklin from NET’s first dance series, A Time to Dance.

Though truncated and all-too-brief, both videos reveal Frederic Franklin’s star presence and transformation into his Streetcar role through strong, virile poses, explosive energy (as in the card game scene), and an aggressive sensual presence throughout — truly a masterfully acted performance expressed in pure movement, sharp timing, and a dominating control of space.

Even the most skilled animator has nothing on the liquid transformations that Frederic Franklin conjured on those videos and in person during my magical meetings with him.

Hits: 2990