“Celebrate what every decade gives to you, not what it takes away.”

On September 2, Marge Champion, the legendary and beloved dancer/ choreographer, begins a new decade in her life — this time as a centenarian.

The advice quoted above, which she often dispensed to me and other friends through the years, will undoubtedly hold firm as she enters a new life journey. Marge will also, I feel sure, be accompanied by her enormous reserves of positive energy, kindness, down-to-earth practicality, and, most important, a great sense of humor about herself and life in general.

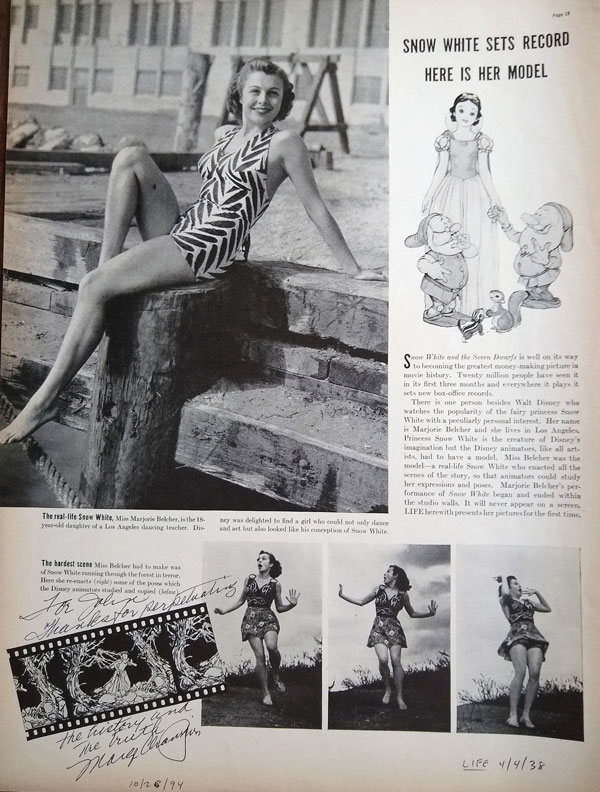

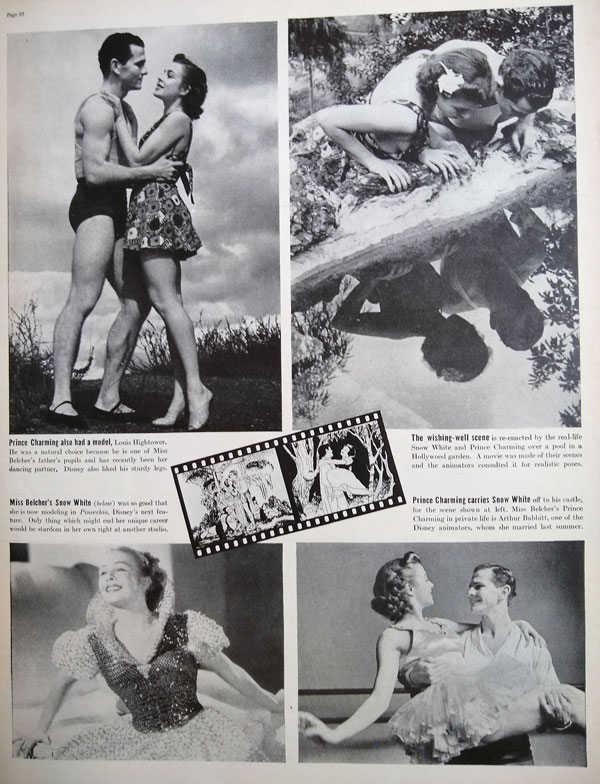

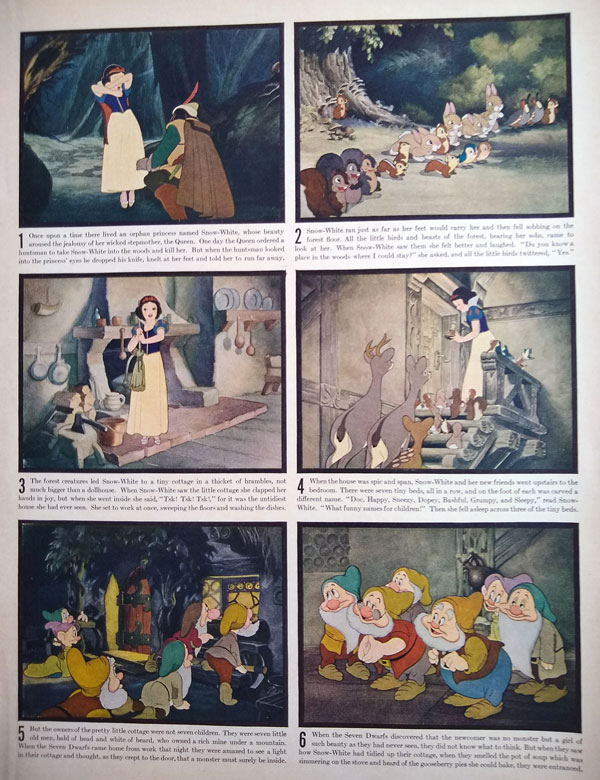

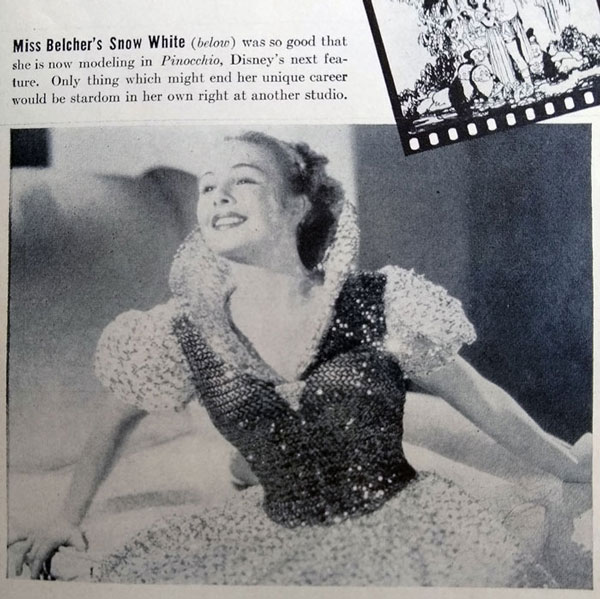

She was born Marjorie Belcher in 1919, the daughter of Hollywood dance instructor Ernest Belcher. Her earliest experience in film was in the mid-1930s when she was a teenager. As many of her fans know, she was the live-action reference model for the princess Snow White in Walt Disney’s first feature-length cartoon, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, released in 1937.

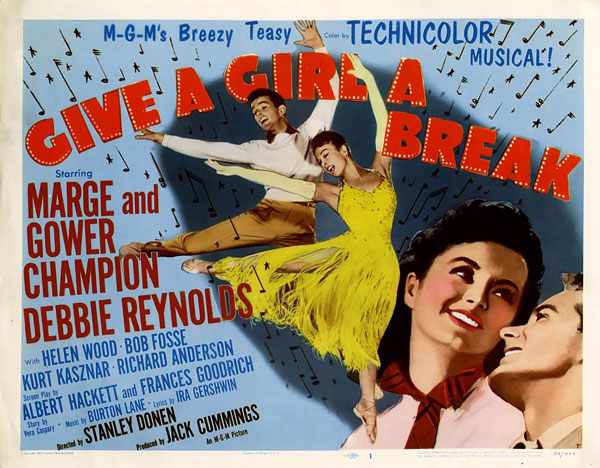

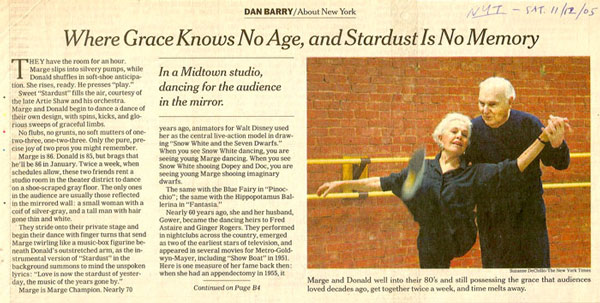

Eventually, Marge gained international fame performing with her husband, the dancer/choreographer Gower Champion (1919-1980), in a dazzling series of MGM musical films. Their featured roles in Show Boat (1951), Lovely to Look At (1952), Give a Girl a Break (1953), among other films, led to lucrative engagements at top nightclubs and early television variety show appearances. They even had their own TV series in 1957.

Marge and Gower Champion’s performances, both on screen and in person, endeared them to audiences around the world. Critic John Crosby described them as, “Light as bubbles, wildly imaginative in choreography, and infinitely meticulous in execution. Above all, they are exuberantly young.”

One of my favorites of the couple’s screen performances is a surreal faux-ballet in the live-action 1955 musical, Three for the Show (1955).

To the classical strains of Swan Lake, Jack Cole’s sardonic choreography presents a most un-Snow White-like Marge as a distraught, jealous, elegantly gowned murderess (the number runs from 37:53 to 44:26). Both Gower and Marge are wonderful in the over-the-top piece; but Marge displays a wide range in this parody of Hollywood musical numbers: she’s sexy, athletic, funny and technically perfect.

On her own, Marge created dances for films (The Day of the Locusts), theatre (Stepping Out; Grover’s Corners) and television; her choreography for the TV special Queen of the Stardust Ballroom won her a 1975 Emmy.

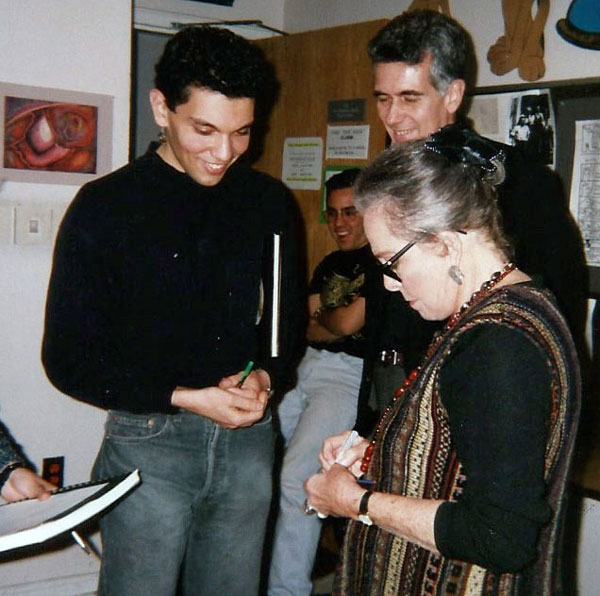

I was introduced to Marge Champion on May 5, 1981 by Art Babbitt (1907-1992) at his wife Barbara Perry’s opening of her one-woman show, Passionate Ladies, on Broadway. Art, a great Disney animator, met Marge during Snow White’s production and became her first husband, briefly. “Our marriage bumped into a career,” he once said of Marge’s desire to excel as a performer. He wanted a housewife, instead of a shooting star.

Some years later, Art married Barbara Perry (1921-2019), a gifted dancer and actress, who often performed with the Champion’s in films, nightclubs and television projects. They were all show biz friends. Laughing, Marge once recalled to me the day Barbara phoned her out of the blue to say:

“You’ll never guess what I’ve gone and done.”

“What?” said Marge.

“I’ve married your old husband!”

Through the years, Marge shared with me many anecdotes about her life and career, privately, but often publicly in interviews on film and stage. She was candid in discussing the tragic death of her third husband, director Boris Sagal (1923-1981). She held on to long friendships with artists she met at Disney, such as master animator Vladimir Tytla and his wife Adrienne; and for years she sent money to help sustain the designer Ferdinand Horvath and his wife Elly.

Her memories of her varied and fascinating career were always sharp and accurate, including her earliest experiences at Disney. She recalled, for example, the small, unadorned stage at the Disney Studio, where for two or three days a month for a couple of years, teenaged Margorie Belcher improvised mime/dance movements that were shot on film. Wearing a long skirt, she moved, danced and emoted as Snow White, sometimes dancing with “gooney, really tall” musicians and animators pretending to be dwarfs.

“The animation supervisor [Ham Luske] would show me the storyboards,” she explained, “a crude set, props, and they had the [soundtrack] playback . . . It was like Mickey [Rooney] and Judy [Garland’s musical films] — let’s put on a show! They’d show me this stuff and turn me loose and I’d do it.”

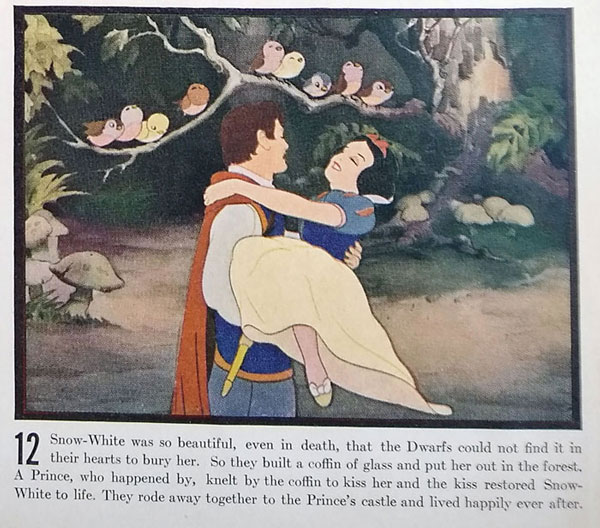

The animators and Walt studied the films, noting the timing of Marge’s actions, studying her pose-to-pose movements, the way her dress and hair moved in every scene.

Preferred takes of Marge’s image were traced frame-by-frame (“rotoscoped”) as a guide to aid the animators in transferring her image to their drawing boards and ultimately the silver screen. For example, the sequence where Snow White runs through a dark forest of grasping tree branches and clinging vines. To aid the animators, Marge acted frightened and improvised a run through a forest mock-up — a clothesline hung with dangling ropes, which she pushed aside while running.

“When I finally saw the finished product,” she says, “I realized that every single movement was mine.” Her pay was “the magnificent sum of $10 a day.”

But she enjoyed the experience, comparing the studio to a high school or college campus. On camera Marjorie Belcher often mimed to the singing of Adriana Caselotti, who provided the princess’ unusual voice. One animator couldn’t resist jumbling and recombining their names into a playful burp: “Margiana Belchalotti.”

Disney and his team were so pleased with Marjorie’s performance, they next hired her as the reference model for the ethereal Blue Fairy in Pinocchio (1940). For Fantasia (1940), she became the stand-in for a huge, but dainty, tutu-clad hippo ballerina. She also directed eleven young women, from her father’s dancing school, as a chorus of Sally Rand fan-wielding ostriches and bubble-dancing pachyderms. “We did stuff with balloons,” she said.

A certain memory of Marge stands out to me: it happened at the 2007 Platform International Animation Festival, one of the best American animation festivals ever, thanks to Irene Kotlarz, the imaginative organizer. She invited me to interview Marge Champion on stage after a screening of a restored print of Snow White, honoring the film’s 70th anniversary.

Early in the day, Marge, a thorough professional, insisted that we check out the theatre and stage where we would converse that evening. “I never step foot on a stage I don’t know,” she explained.

That night, we sat together in the audience, Marge watching the movie she’d made over seven decades ago; me watching and listening to her delighted reactions and whispered comments. It was a lovely, strange feeling to sit next to Snow White, as she watched herself on the screen.

On screen, as Snow White was awakening from the Prince’s kiss, an usher summoned us backstage to prepare for our on-stage conversation. In the dark, separated by a giant screen on which animated cartoon characters played their final scenes, with music swelling loudly on the soundtrack, Marge bid me goodbye as she was guided by flashlight across the stage, behind the giant movie screen. She would make her entrance after my introduction from the opposite side of the stage, as rehearsed.

While waiting for the film to end, I had the privilege to experience a wonderful, time-tripping sight. On the huge movie screen, a gigantic Princess kissed gigantic dwarfs goodbye, and a gigantic Prince carried her to his horse,rode into a shimmering sunset toward a castle emerging from mist, while a chorus with full orchestra sang “Someday My Prince Will Come.” I could see all that on the huge screen. Then, stepping to the left I saw Marge, age 88, way across the stage exercising, stretching, getting herself ready to meet another audience, as she did at Disney’s little sound stage, or New York’s posh Persian Room at the Plaza Hotel, or the London Palladium, as she did before facing MGM’s Technicolor cameras, or audiences in Leningrad and Moscow.

Step to the right – there she was again as Snow White.

Step to the left: a little lady, a true professional, preparing herself to meet the public, to give the folks a great show.

And she did.

Hits: 6280