One of the many advantages of living in New York City is access to once-in-a-lifetime art exhibitions. A magnificent example is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, now through February 12, 2018: Michelangelo – Divine Draftsman & Designer.

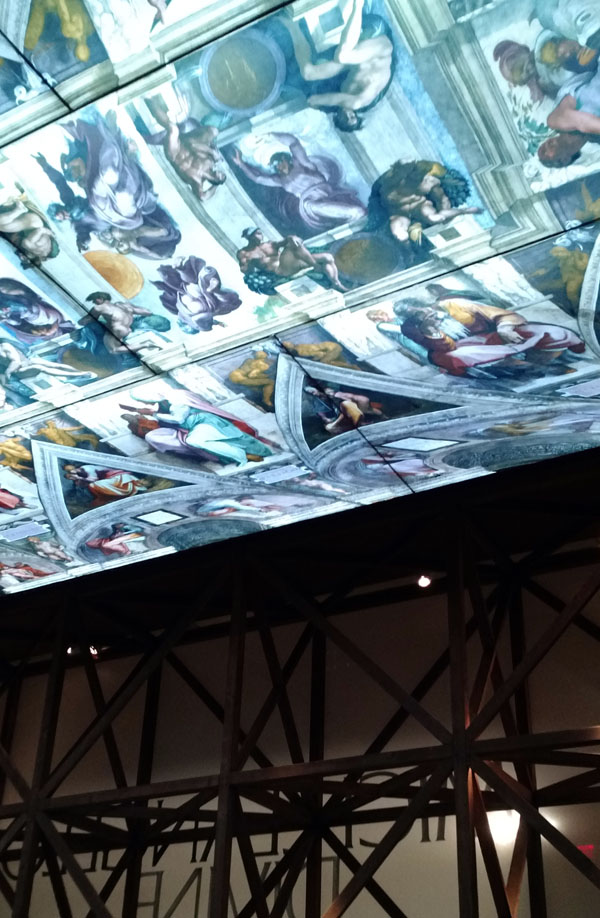

For the first (and perhaps only) time, this unique showcase brings together more than 350 artworks from 53 different museum collections, including The Royal Collection at Windsor Castle and the Vatican Library.

The main focus is the creative process as revealed in drawings by Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475 – 1564) the great Italian Renaissance master artist whom his contemporaries described as “il Divino.” The divine Michelangelo used “drawing as a language,” according to the exhibition’s curator Carmen C. Bambach. “It’s what unifies his career,” which included sculpture, design, painting and architecture.

133 drawings and three marble sculptures display the artist’s ability to make graphic lines and blocks of stone come to forceful, vital life. Michelangelo drew like a sculptor. In fact, a chisel was his preferred tool rather than a brush. (“I am not a painter,” he said.)

Even the fragmentary anatomy of his sculpture “Young Archer” exudes movement: the slender, coltish adolescent strides off with a subtle torso twist, his confident, curly head tossed to one side. Art historian Francesco Caglioti suggests that the “incomplete, almost spherical element” of the archer’s twist of his body and head, expresses “in its principle of rotation the unmistakable signature of Michelangelo.” In a drawing rediscovered in 2003 of the complete statue (made by a follower of Michelangelo), the archer’s right arm reaches across his chest to join the left hand in retrieving an arrow from the quiver; but the dynamic body and head twist is the primary life-giving movement.

The carving of the sculpture is dated circa 1496-97, when Michelangelo was in his early twenties. “With this sculpture,” writes art critic Holland Cotter, “he had found what would be his favorite subject, and the one that would make his name: the heroic male body.”

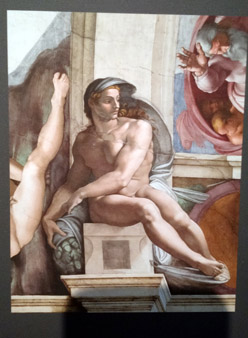

Movement also defines seated figures. Here are two versions of one of the twenty athletic nude male youths, known as the Ignudi, used by the artist as narrative linking devices to direct the eye in the Sistine Chapel ceiling frescos. The study rendered in red-chalk with white gouache highlights, and the final painted version show a twisting figure reaching behind himself. In the finished painting, his cloak billows in the wind, adding another element of motion.

Sharp, definite lines delineate Michelangelo’s forms, shaded by intricate cross-hatching. There is none of the smoky sfumato shading and chiaroscuro of his older rival, the other great multifaceted genius of the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519).

However, Michelangelo’s art could also be delicate and tender, as in this unusually detailed portrait (1531-34) — a subtly animated three-quarter turn of the head of Andrea Quaratesi, a young man thirty-seven years Michelangelo‘s junior, who “captured the artist’s heart,” according to the curator. The picture is “not unlike the type of portraiture Leonardo da Vinci pioneered with his Mona Lisa.” Both artists sought to portray not only moti corporali (motions of the body), but how it relates to atti e moti mentali (motions and emotions of the mind).

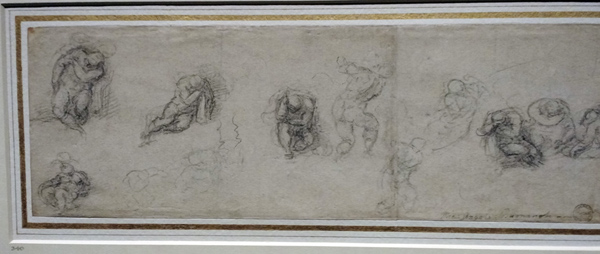

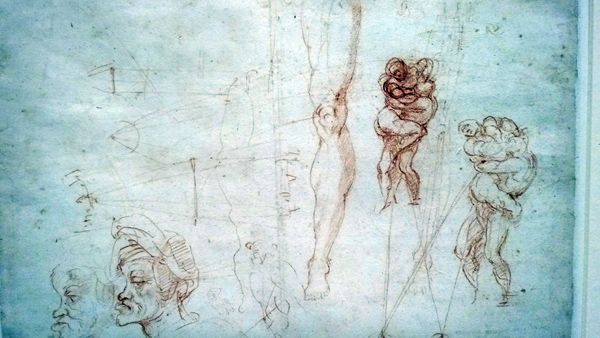

This glorious exhibition showcases of one of pre-cinema’s greatest “animators.” I found it a joy and a deeply moving privilege to view and study up-close Michelangelo’s 500-year old drawings. Especially the rough, thumbnail doodles that search tirelessly for the correct pose and clarity in staging. These small-sized animated roughs contribute mightily to the complex action and overpowering dynamism of finished works.

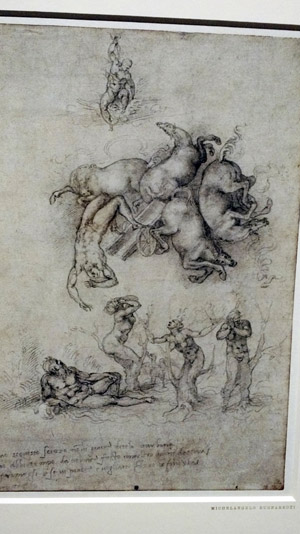

Here, for example, a preparatory narrative drawing of tragic Phaeton, a Greek mythological figure similar to disobedient Icarus. As Zeus smites him and his steeds from the sky, Phaeton’s grieving sisters begin to morph into poplar trees.

Fall of Phaeton.In a final (and more balanced) layout, the master artist shows off his ceaseless imagination and superb draftsmanship by changing the actions of all the players. He re-positions Zeus astride his eagle companion, and shows the falling, doomed Phaeton and difficult-to-draw horses in even more virtuosic poses.

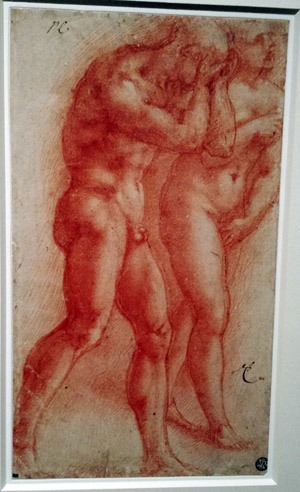

The personal restlessness of the artist comes through in the actions of his figural sketches. His “actors” express emotions through energetic movements. Adam and Eve flee in shame and despair after banishment from Eden, above; below,Hercules struggles vigorously with a lion, the giant Antaeus, and a dragon/ hydra.

Even inert forms shimmer with energy, such as the sleeping apostles’ uncomfortable, agitated Agony in the Garden.

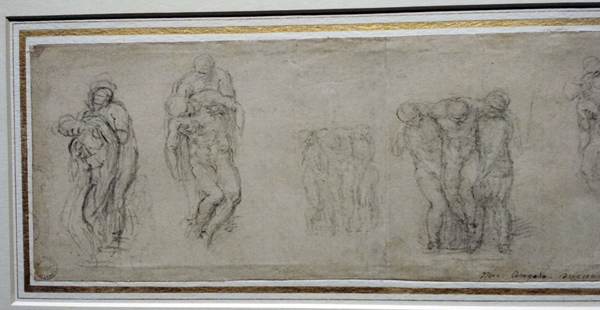

In thumbnail sketch explorations for the Pietà and the Entombment, the feeling of weight is visceral in the figures handling of the deceased Christ’s body.

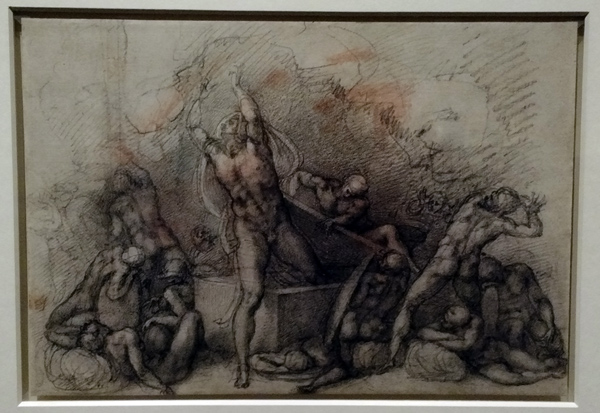

A glorious contrast is the Resurrection scene, shown above and below, as the now-vital Christ thrusts himself out of the tomb to the amazement and fright of the tomb’s guards. Much dazzling energy and visual narrative information is imparted in these two economically drawn, small, rough chalk sketches.

The Michelangelo treasure trove at the Met sheds intimate light on the mind of their creator. “We can see him thinking, having a conversation on the sheet of paper,” Ms. Bamback asserts. “We see him inventing, or just having fun, doodling. A sense of intimacy, of immediacy, it’s like glimpsing over the shoulder of this genius.”

His creative process and eclectic mind is seen on many work sheets of paper, including corrections he drew on his student’s practice sheets. They were often accompanied by sharp demands: “Copy this Madonna and breathe life into her!”, “Shape a leg, make an ear!”, “Draw me an eye and put expression in it.” The strict, hard-to-please master teacher could also be paternal: “Andrea be patient”; “Draw Antonio, draw Antonio, draw and don’t waste time.”

This exercise sheet features drawing lessons by the master. The profile at extreme left is by a pupil imitating the Master’s drawing next to it. The two poses of wrestlers are also by Michelangelo. The poorly rendered leg and other incidental sketches are by students.

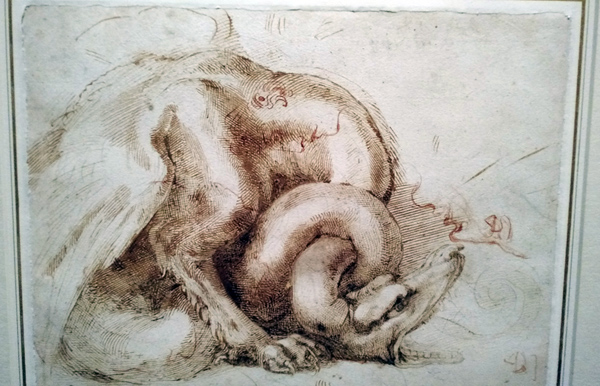

This study by the Master over sketches of heads by a pupil, a ferocious dragon ensnared by its own tail might be a comment on the teacher’s frustration with his students.

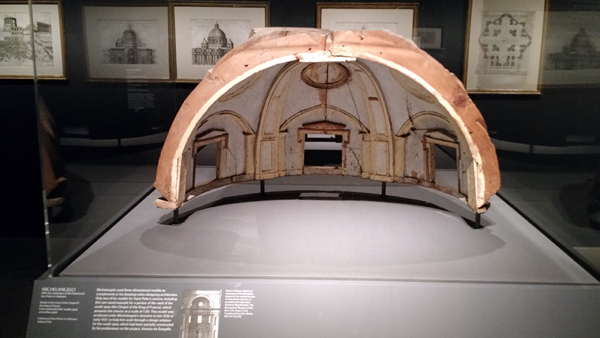

One of only three surviving wood models for Michelangelo’s architectural projects. This model complimented his drawings of the Vault of the Chapel of the King of France.

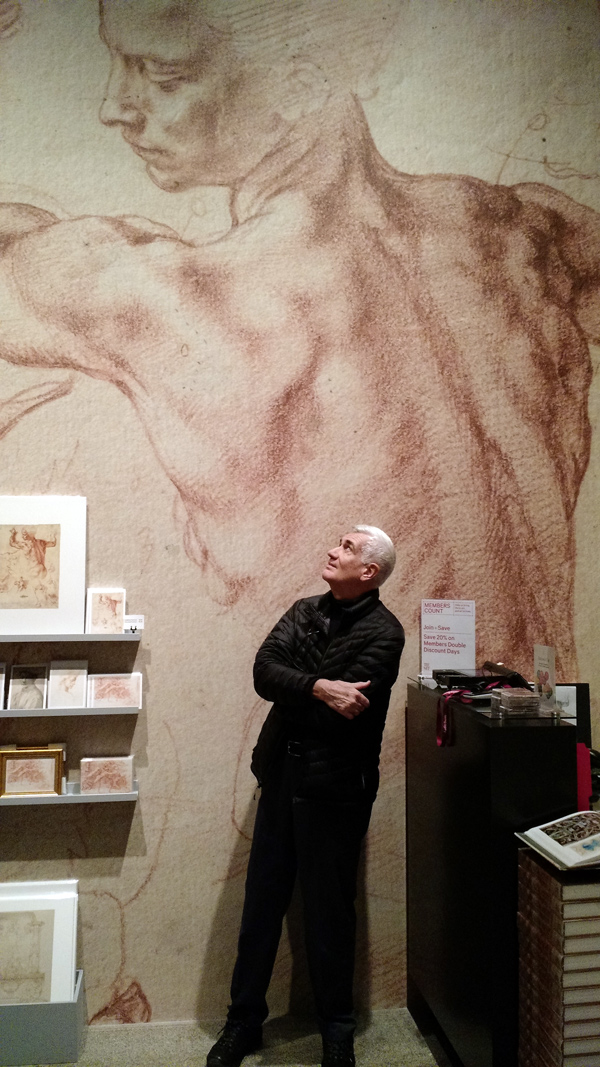

My sincere thanks to Emily Sutter, Digital Learning Program Producer & Editor, Metropolitan Museum of Art — and former animation student of mine at NYU Tisch School of the Arts — for arranging a private tour of the exhibition, before it opened to the general public.

It was so wonderful, on a cool, mid-November Sunday morning at 9 a.m., to wander at leisure through the exhibition rooms at the Met with only a few people – employees and sponsors — and to spend quality time looking and studying, up close, the art of Michelangelo.

Hits: 3559

This is one of the great advantages of being in New York. You have made such a well considered documentation that it gives this rare exhibition of Michelangelo the context of being as close as one can in the galleries.

Once again, great description of the Met exhibition. Thanks, John for this wonderful article. Michelangelo was (and still is) a genius, a true Master. By the way, I loved the qualification of Michelangelo as the “pre-cinema’s greatest “animators”. Thanks again, John! Keep writing!