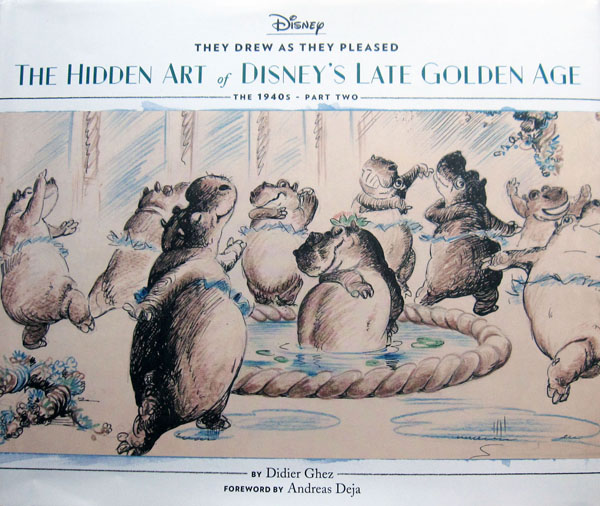

They Drew As They Pleased – The Hidden Art of Disney’s Late Golden Age:

The 1940s – Part Two

by Didier Ghez

Chronicle Books, 2017

On October 10, Chronicle Books will publish a third volume in an informative series about Walt Disney Studio concept artists and their art: They Drew As They Pleased – The Hidden Art of Disney’s Late Golden Age: The 1940s – Part Two.

Author Didier Ghez (Disney’s Grand Tour; The Disney History blog; Walt’s People book series) again displays formidable skill as a researcher and animation historian. His is an amazing, Sherlockian investigatory ability to sleuth out “lost” Disneyana artworks, and info about its artists, in unexplored private collections, as well as the vast holdings of the Walt Disney Archives and Animation Research Library. Selective excerpts from private diaries and personal correspondence especially illuminate artists’ lives and the day-to-day workings of Disney’s dream factory in its Golden Era of the 1930s and 40s.

The book series has sparkling reproductions of photos and color/black-and-white drawings, and imaginative layout designs by Cat Grishaver, showcasing a treasure trove of little-known “inspirational sketch artists.”

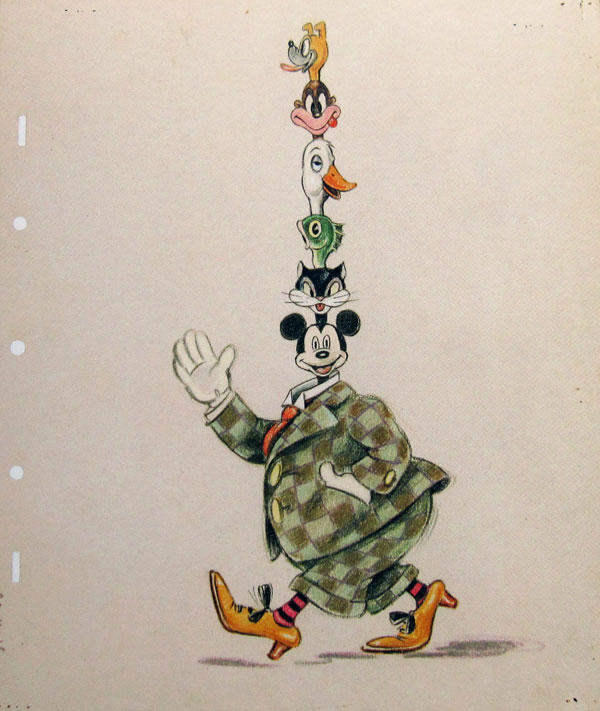

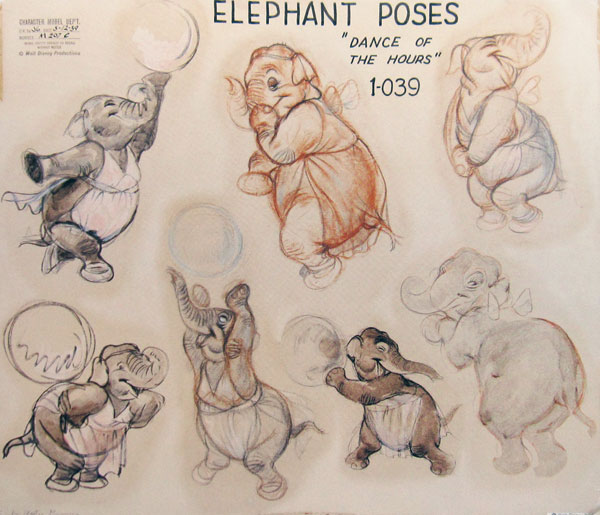

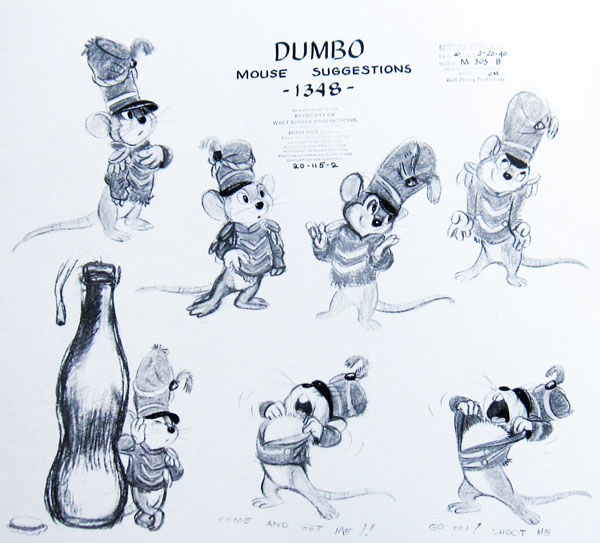

In the Disney Studio film production pipeline (and other studios), the inspirational or conceptual artists were (and continue to be) among the earliest creative personnel to visualize characters and stories for now-classic Disney animated films. Many were part of the Character Model Department in the late 1930s, a so-called “think tank” that encouraged exploration of a film’s visual/narrative possibilities through character designs (“idea sketches”) drawn in their own styles, using watercolor, oil, pencil, pastel, even plaster maquettes.

Many artworks showcased in the They Drew As They Pleased series, selected by Ghez from hundreds of examples, are stunningly inventive and beautiful; and often more interesting than the imagery that finally appears on the screen. The hand (graphic “signature” or style) of an individual artist is apparent within the still art; but assembly-line production exigencies to make the drawings move (e.g., cel techniques involving multiple artists and artisans), and commercial considerations (audience appeal), favor uniformity in setting a final look.

The current volume encompasses the work of Eduardo Sola Franco, Johnny Walbridge, Jack Miller, Campbell Grant, James Bodrero, and Martin Provensen.

Some Animated Eye thoughts:

Johnny Walbridge (above) impresses with his versatility: from graceful, precise designs of balletic flowers, mushrooms, and goldfish for Fantasia; to mechanically exact railroad equipment for Dumbo’s circus train and outrageous circus clowns’ sight gags; to wildly imaginative monsters for Alice in Wonderland (my fav: a badminton racket-tailed ostrich whacking a small, beaked shuttlecock).

Jack Miller and Martin Provensen were both superb character designers, blessed with an always appealing, deceptively simple, graphic line expressing a character’s many moods. I love their work, but think due to their close proximity in the Character Model Department hothouse, they developed similar styles, sometimes making it difficult to tell them apart.

Disclaimers throughout the book regarding several artworks of uncertain origin (“in the style of”) allude to my point. Provensen is quoted regarding “Disney tricks in drawing which I found I didn’t like . . . [such as] A certain facility toward expression; a too-facile approach toward gesture, toward expression, toward posture . . .”

Campbell Grant held a facility for mimicking other artist’s styles. His continuity sketches (pastel on black paper) for Fantasia’s “Night on Bald Mountain” match closely the dark, decorative style of famed illustrator Kay Nielsen, the sequence’s art director. Grant’s ostrich-ballerina-ala-Degas pastels are brilliant; but were it not for his initials on the character’s model sheets, one might think they were drawn by Provensen or Miller. Interestingly, when all three artists left Disney’s employ in the 1940s, each explored a more personal stylization in the children’s book illustration field.

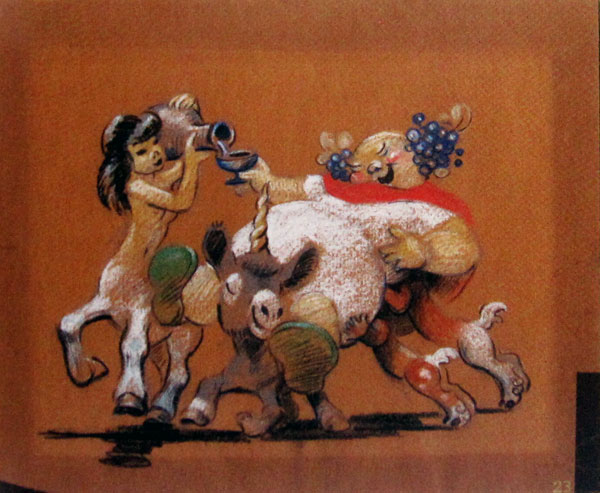

James Bodrero, a worldly bon vivant, brought a sensuality and urbane wit to his easily identifiable story/concept drawings for Fantasia’s “Pastoral Symphony” section. His swarthy, lusty centaurs, bare-breasted (with nipples) centaurettes, never made it intact to the screen, although fat Bacchus’ tumescent state is implied by his donkey’s strategically placed horn.

Likewise abandoned were Bodrero’s slyly sexual ideas for the “Dance of the Hours,” e.g, a zaftig elephant wearing round her ample hips a “tutu” made of live linked alligators (!), and his violent story sketches of giant predatory rodents, for a proposed “The Mouse’s Tale” section in Dumbo.

Likewise abandoned were Bodrero’s slyly sexual ideas for the “Dance of the Hours,” e.g, a zaftig elephant wearing round her ample hips a “tutu” made of live linked alligators (!), and his violent story sketches of giant predatory rodents, for a proposed “The Mouse’s Tale” section in Dumbo.

Most interesting of Ghez’s discoveries in the current edition is Eduardo Solá Franco (1915-1996), a gifted Ecuadorian painter of distinctly personal, loose, imaginative watercolors, who had the briefest of tenures at Disney. Hired in May 1939 to create concepts for Don Quixote (ultimately abandoned), he was gone by October, leaving behind a slew of detailed ideas for scenes and characters from Cervantes’ novel in highly refined, kaleidoscopic, colored and black and white watercolors, reminiscent of Florine Stettheimer.

I am grateful to Didier Ghez’s book for ending my ignorance of this special artist. A selection of quotes from the artist’s illustrated diaries offer an intimate glimpse into his emotional peaks and valleys while at Disney.

I am grateful to Didier Ghez’s book for ending my ignorance of this special artist. A selection of quotes from the artist’s illustrated diaries offer an intimate glimpse into his emotional peaks and valleys while at Disney.

Ghez inspired me to investigate the life of Eduardo Solá Franco. I believe he deserves a comprehensive biography of his own, to include all of his illustrated diaries. Disney was only a tiny part of his restless, yet prolific creative life. He was a painter, sculptor, illustrator for magazines and film, designer of stage scenery (for the Joffrey Ballet), choreographer of his own ballets in Lima, playwright, director of award-winning experimental short films; he was also a closeted gay man who struggled with accepting his sexuality, and, for a time, served as the Ecuadorean Cultural Attache in Rome.

The following 2011 article “The Unclassifiable Eduardo Solá Franco”

from a Quito, Ecuador blog, Under the Northern Star, offers an intriguing overview of Franco’s life and career: http://underthenorthernstar.blogspot.com/2013/10/the-unclassifiable-eduardo-sola-franco.html

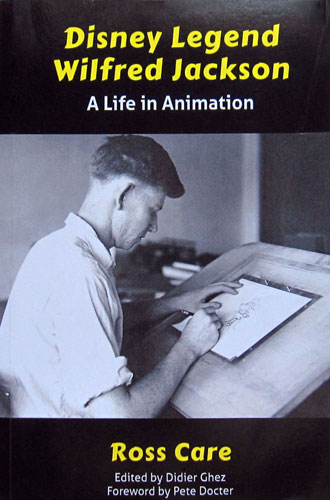

Disney Legend Wilfred Jackson – A Life in Animation

Disney Legend Wilfred Jackson – A Life in Animation

by Ross Care

Theme Park Press, 2016

In-depth books abound detailing the lives and analyzing the films of live-action directors. Similar in-depth studies about animation film directors are rare. This is partly due to the anonymity and collaborative nature of the animation process. Even longtime fans are hard pressed to come up with names of the directors of favorite Disney features and shorts. Also, the general public doesn’t know what animation directors do, or how they do it. George Cukor directing Greta Garbo and Robert Taylor is easily explainable; but how David Hand coaxed a performance out of Bambi and Faline is a bit more problematic.

Ross Care’s recent biography of Disney director Wilfred Jackson (1906-1988), published last year by Theme Park Press and edited by Didier Ghez, is a fine animation biography, with detailed critiques of animated films and cogent descriptions of how they were made.

Jackson, nickname “Jaxon,” is considered by many to be Disney’s finest, most exacting/details-oriented director of shorts and feature film sequences. He began in 1928 as a lowly assistant animator, and immediately proved his worth by inventing a method of pre-timing animation used in Steamboat Willie, the first Mickey Mouse short to incorporate sound.

Jaxon’s intelligence, organizational gifts, creativity and punctilious work ethic soon led to dozens of directing assignments on shorts (three won Academy Awards). During thirty years at the studio, Jaxon’s stand-out sequences, often involving music, enhanced Fantasia, Dumbo, Cinderella, Peter Pan, and seven other features.

Care is a composer and among the first writers to publish serious critiques and histories of classic era Disney music and musicians. (Full disclosure: Ross Care composed scores for my films The Wizard’s Son (1981), Otto Messmer and Felix the Cat (1977), and adapted Mendelssohn’s scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream for Bottom’s Dream (1984).)

He benefited greatly in this book from seven years of correspondence between himself and Jackson. Jaxon’s letters to Care, and a diary also published in this book, contain the director’s intimate thoughts, opinions and eyewitness accounts about making Disney films. Truly revelatory, they form an invaluable core for the book, augmented by Care’s cogent discussions of Jaxon’s life and films.

Ross Care will speak on Wilfred Jackson and sign books at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco on Saturday, Sept. 23 at 1 p.m. Ticket information: http://waltdisney.org/

Too Fat Too Slutty Too Loud – The Rise and Reign of the Unruly Woman

by Anne Helen Petersen

Plume (Penguin Random House), 2017

A sharply written, timely book celebrating the increasing visibility and power of contemporary women who shatter walls and glass ceilings by challenging age-old perceptions of what constitutes “acceptable” feminine behavior. The election of our unhinged, unethical president and his regime’s backward agenda of resentment and prejudice sparked strong grassroots resistance, particularly among women. Examples include the amazing Women’s March in Washington and other cities across the country after the inauguration; the “Nevertheless, she persisted” rallying cry of a movement of feminists and supporters of Senator Elizabeth Warren, forced into silence during Senate hearings for a racist attorney general; and the three female GOP senators (Shelley Moore Capito (West Virginia), Lisa Murkowski (Alaska), Susan Collins (Maine) who pulled the rug out from under testosterone-fueled senators attempting to repeal the Affordable Care Act with no backup plan.

Author Petersen examines women perceived to be “too queer, too strong, too honest, too old, too pregnant, too shrill, too much,” focusing on eleven powerful pop culture celebrities with kick-butt attitudes, and why they are loved and hated, including Serena Williams, Melissa McCarthy, Abbi Jacobson, Ilana Glazer, Nicki Minaj, Madonna, Kim Kardashian, Hilary Clinton, Caitlyn Jenner, Jennifer Weiner, and Lena Dunham. This book accounts, writes Petersen, “for the ways in which unruliness has been historically censored, and the ways in which it is more necessary than ever.”

Recommended reading for both sexes in the animation industry, where women continue to be underrepresented.

Hits: 3733