In 1959, I was sixteen and already deeply interested in animation. In Elmira, New York, my hometown, I scrambled for information on the history of the art form and how to make my own cartoon films. Initially, my curiosity was sparked by two television series: Disneyland (1954) and The Woody Woodpecker Show (1957), where, respectively, “Uncle” Walt Disney and “Uncle” Walter Lantz would occasionally demonstrate their animation “secrets.” In fact, the 1955 Disneyland program “The Story of the Animated Drawing,” introduced me to the earliest film animators, including the genius comic strip cartoonist and animator Winsor McCay, whose biography I would write three decades later.

At the time, books on animation history and/or the medium’s techniques were few.

But, like water on a desert, they were life savers: informative, profusely illustrated and inspiring.

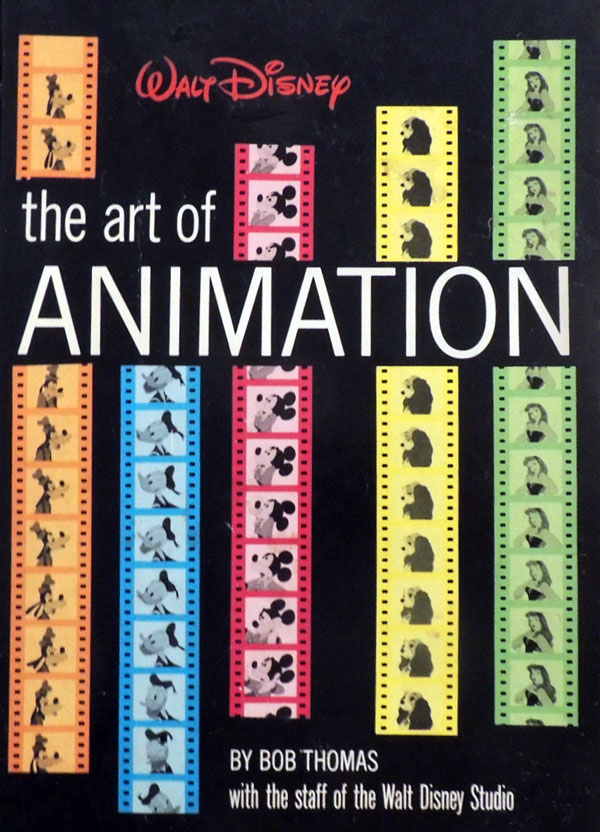

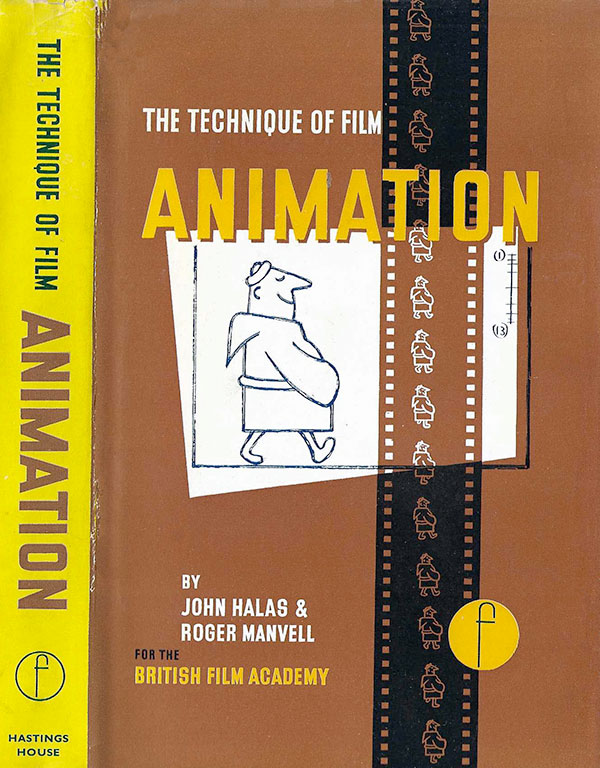

Bob Thomas’ The Art of Animation (1958), for example, a lavishly illustrated tome promoting the making of Disney’s 1959 feature Sleeping Beauty, also included a small section on pre-Disney animation. There was also Preston Blair’s Advanced Animation, an iteration of his enduring 1947 how-to manual on Hollywood cartoon principles. And Britain’s John Halas & Roger Manvell’s The Technique of Film Animation (1959) offered tantalizing glimpses of international/avant-garde animation.

I devoured each book, and searched for more information in local libraries and, primarily, at The Art Shop, a small Elmira store that sold artists materials, painting restorations and framing. Arthur Rosskam Abrams (1909-1981), the kind-hearted owner, was an exhibited abstract painter and lecturer who encouraged my flipbook experiments, sequential drawings and my many annoying questions. He and his wife Sally also allowed me to study and draw an original Disney cel and background setup they owned from the Courvoisier Gallery in San Francisco of Mickey Mouse in Fantasia (1940).

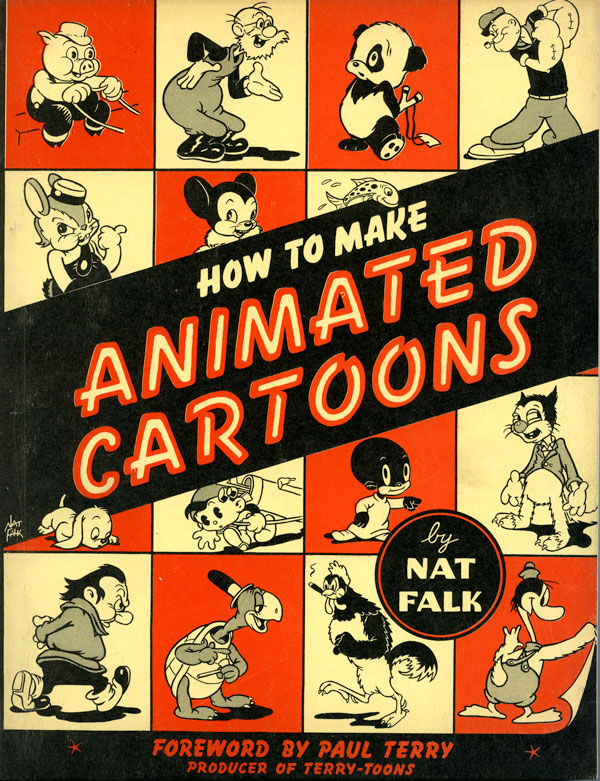

A picture framer at The Art Shop, Delos Smith, was also supportive and generous. He gave me two older books on animation that he owned: The Art of Walt Disney (1942) by Harvard professor Robert D. Feild, the first serious analysis of Disney’s contributions to the development of character animation. The other book was a paperback edition of How to Make Animated Cartoons, published in 1941 by Foundation Books, New York, written by an illustrator named Nat Falk.

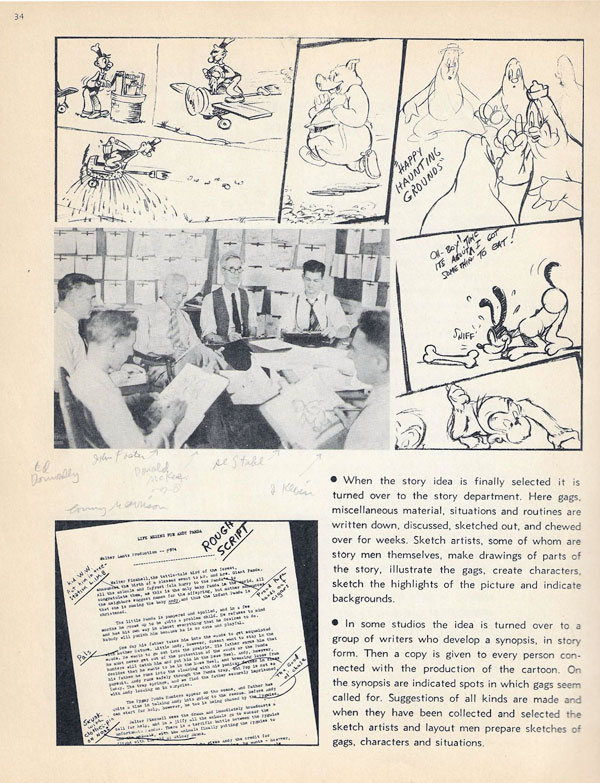

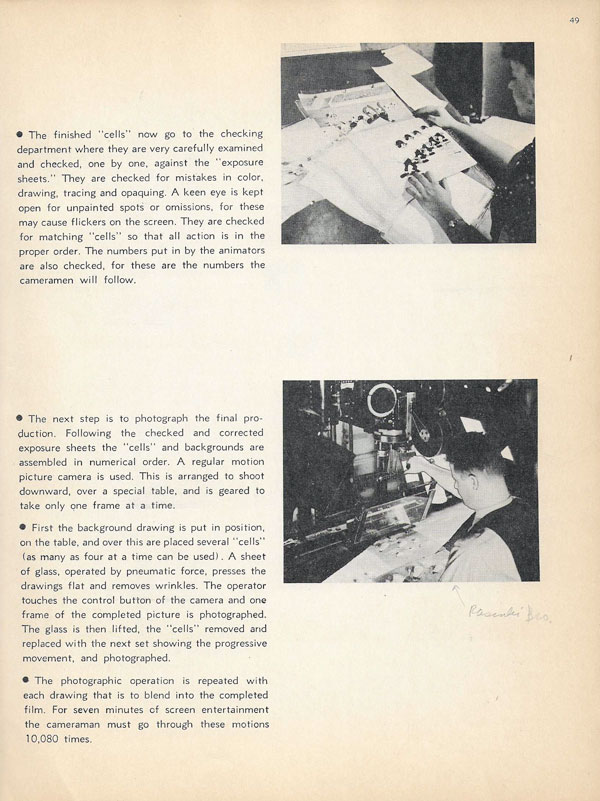

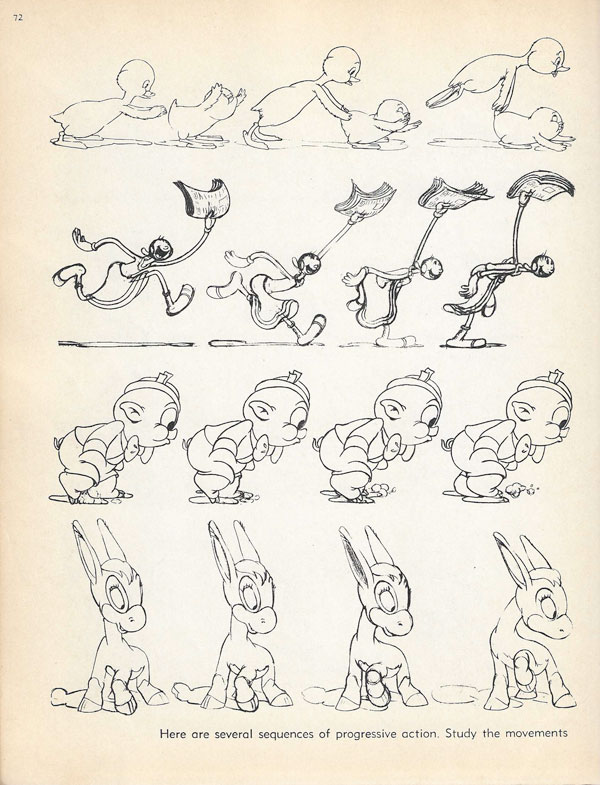

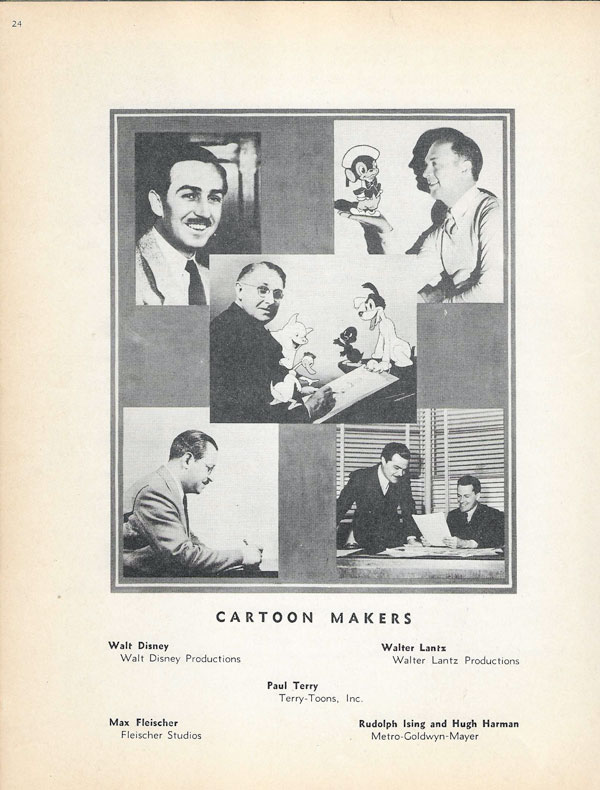

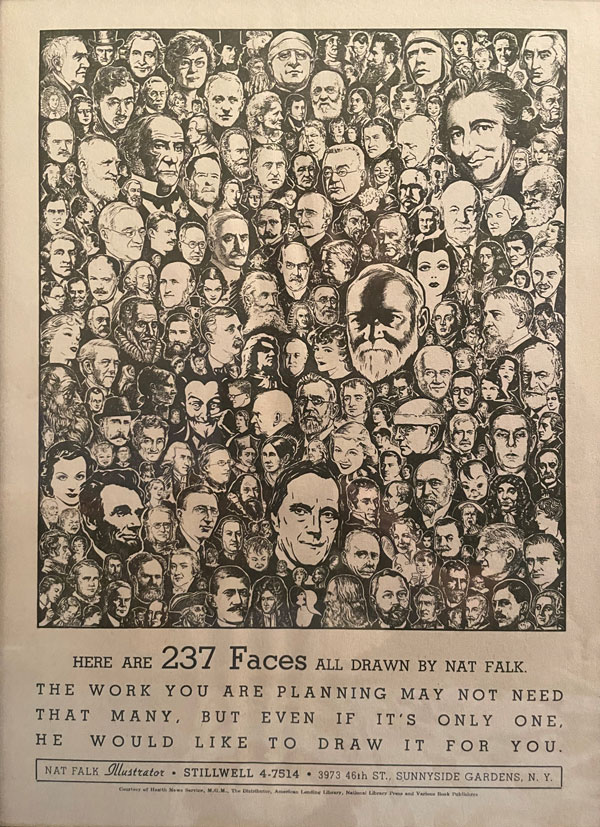

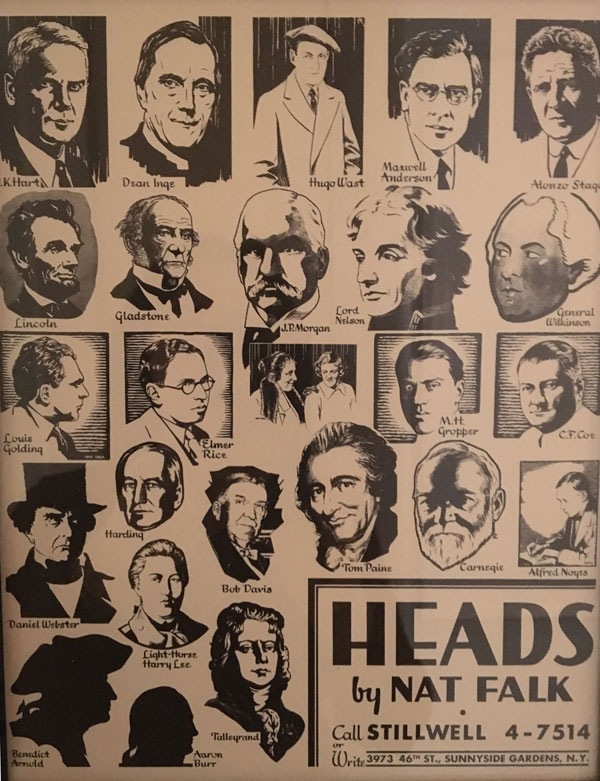

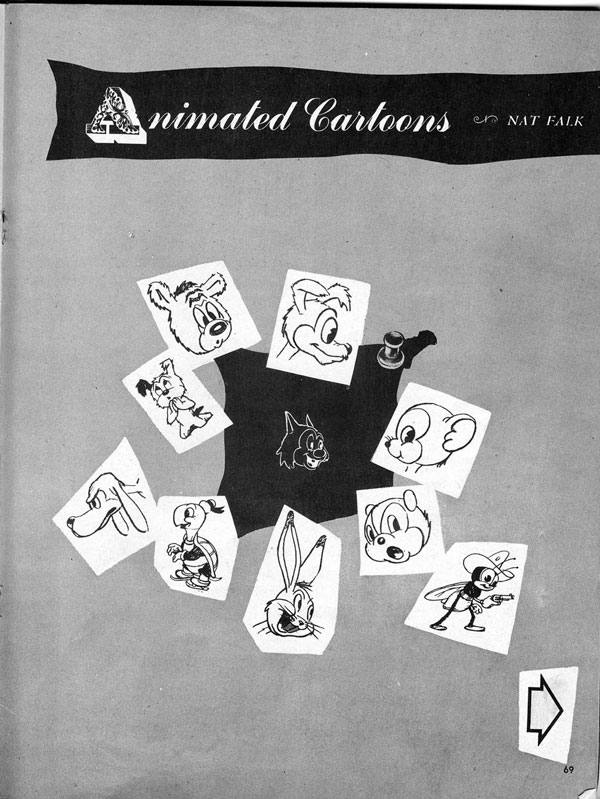

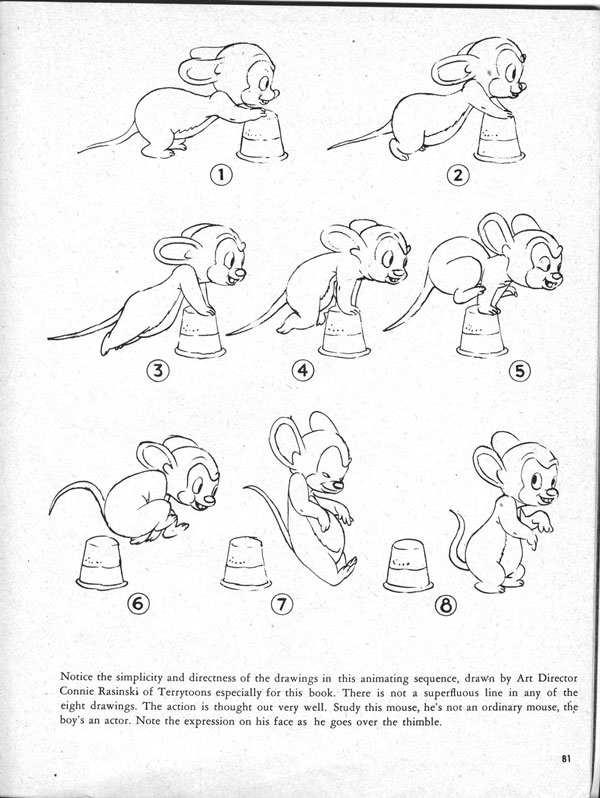

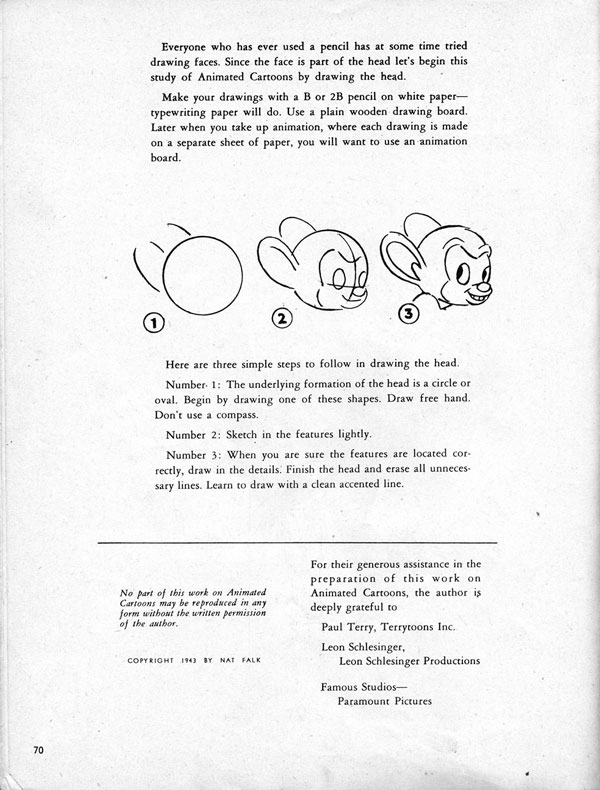

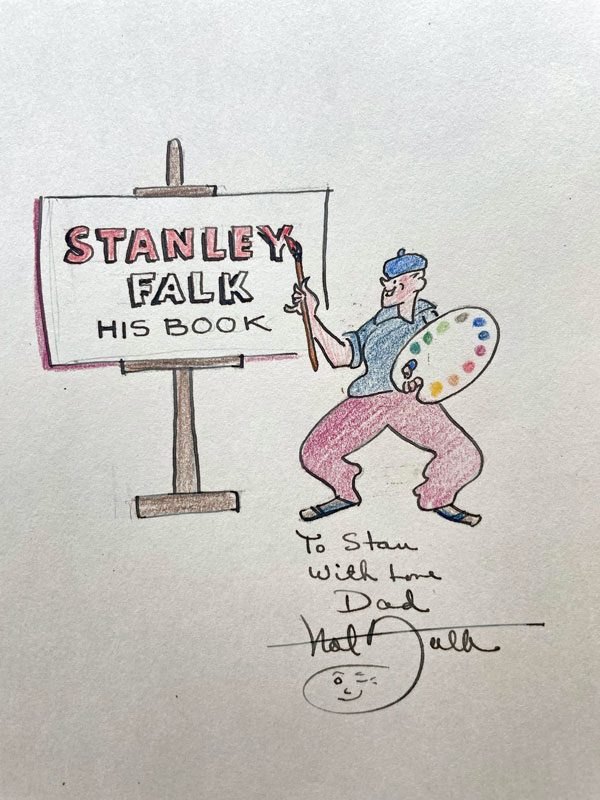

Below, four pages from Nat Falk’s How to Make Animated Cartoons:

I found both books illuminating. The Falk book was particularly revelatory in its detailed information about “early attempts to obtain motion in drawings.” Its 80-pages include a concise history of motion in a larger pictorial art tradition — e.g., the prehistoric “wild boar of Altamira,” Temple of Isis, and Leonardo, among others, through 19th century pre-cinema mechanical toys (Thaumatrope, Phenakistoscope, Zoetrope, “Flipper Books,” etc.), and a section on early “contributions of the early 20th century” silent film animators (McCay, Bray, Hurd, Messmer and others).

I found both books illuminating. The Falk book was particularly revelatory in its detailed information about “early attempts to obtain motion in drawings.” Its 80-pages include a concise history of motion in a larger pictorial art tradition — e.g., the prehistoric “wild boar of Altamira,” Temple of Isis, and Leonardo, among others, through 19th century pre-cinema mechanical toys (Thaumatrope, Phenakistoscope, Zoetrope, “Flipper Books,” etc.), and a section on early “contributions of the early 20th century” silent film animators (McCay, Bray, Hurd, Messmer and others).

There is also a showcase of seven contemporary (circa 1941) American cartoon studios, including Fleischer Studios, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Cartoon Division (Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising); Walter Lantz Productions, Leon Schlesinger Productions, Screen Gems, Inc., and mostly on Terry-Toons Inc. Paul Terry, a friend of the author, wrote the book’s foreword and provided most of the illustrations of animation production processes.

The Disney studio refused Falk permission to use Disney artwork and photos, possibly due to the pending publication of Field’s Art of Walt Disney book. I speculate that fourteen years later, researchers for the Disneyland TV show on “The Animated Drawing” referred to the Falk book as an informational source on early animation.

Falk’s How To book influenced a generation of World War II babies and Boomers who became animation artists and film historians. In the first paragraph of his 2009 instructional book, The Animator’s Survival Kit, Richard Williams writes about discovering Falk’s book in 1943, when he was ten years old. “The book was clear and straight-forward,” Williams relates, “the basic information of how animated films are made registered on my tiny ten-year-old brain and, when I took the medium up seriously at twenty-two, the basic information was still lurking there.” He also “used it as a handy reference guide for 1940s Hollywood cartoon styles when I designed the characters and directed the animation for Who Framed Roger Rabbit.”

When I wrote my first book, The Animated Raggedy Ann & Andy – An Intimate Look at the Art of Animation Its History, Techniques and Artist (1977,) I often thought about Nat Falk’s sincere, direct writing style, and how he managed to organize and share so much information succinctly about various areas of animation. I have long wanted to know more about him and his background.

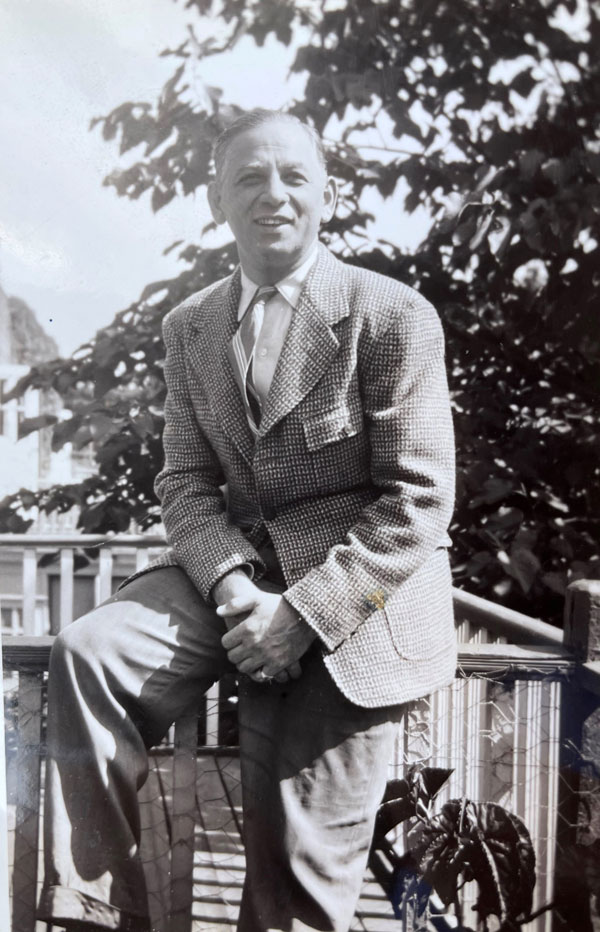

In August 2022, nearly sixty-three years after first receiving Falk’s book, I had the good fortune to meet and talk with his son and his granddaughter. Karen Falk is a historian who serves as the head archivist for The Jim Henson Company. She authored Imagination Illustrated: The Jim Henson Journal and has contributed to numerous non-fiction books, and collaborated on many Henson exhibits, including the spectacular, permanent The Jim Henson Exhibition at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image. Stanley L. Falk is former chief historian of the Air Force and a military historian specializing in World War II in the Pacific, the author of five books on the war in the Pacific arena, several textbooks on national security affairs, and numerous essays, articles, and reviews. 1

With their generous participation and help, I offer you the following appreciation of Nat Falk, multi-talented illustrator, researcher and author; a polymath interested in traditional and modern arts, including film animation; a man who took joy in word play and playful imagery (he loved reciting for his children the 1895 poem “The Purple Cow” and teaching them lyrics to the 1918 pop song “Can You Tame Wild Wimmen?” 2 A warm, gregarious soul interested in people and learning about their lives. As his granddaughter recalls, “Grandpa collected people.”

Nathan Isaac Falk (1898-1989) was born in Baltimore, Maryland to Lithuanian Jewish parents, Alexander Aaron Falk and Sarah Naomi Block. Nat had nine siblings – four brothers and five sisters, all living comfortably in a large house. His father, Alexander Falk, made men’s trousers, cutting the fabric on-site, having them manufactured and then selling wholesale up and down the easter seaboard. It was called Stylecraft Trousers. Nat’s sisters worked in the office. Nat, when he was a teen, made advertisements. “It was a good business,” Stan Falk states.3

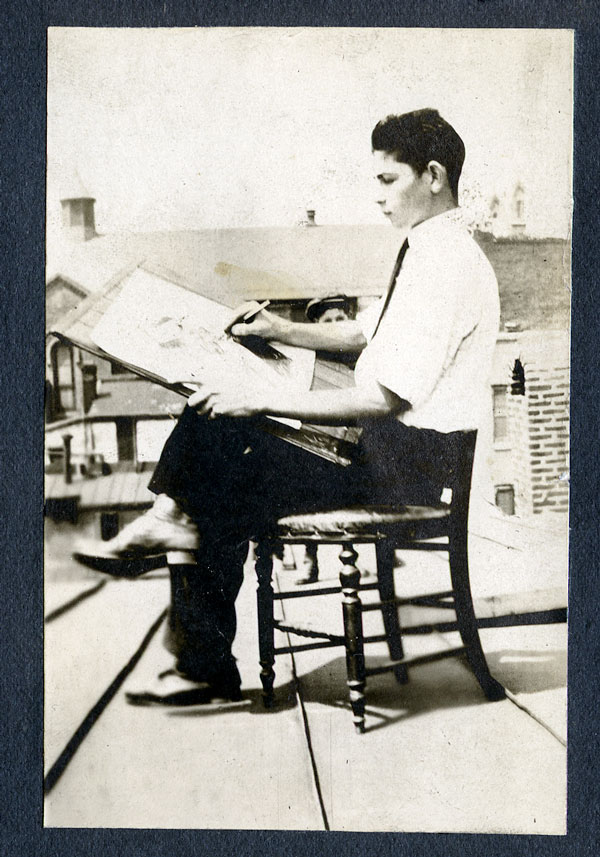

As a child, Nat drew constantly and created “chalk talks” to entertain his family and neighbors, inspired by performances he saw in Baltimore’s vaudeville theatres. Falk would draw an image, quickly erase it, then add new chalk strokes, an “act” accompanied by slight-of-hand magic tricks and a glib patter of jokes.

Before America entered World War I, young Falk entertained troops at a Maryland military camp. His quick-sketch/magic performance impressed Emerson Harrington, the Maryland governor, who offered him a scholarship to the Maryland Institute of Art in 1916.

The next year, when he was 19, he became art editor of The Club magazine of the Alliance Athletic and Literary Club of the Jewish Educational Alliance in Baltimore.4 During this period he was also commuting from Baltimore to Washington delivering ads he drew for Hecht’s department store.

At age 21, Falk attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, America’s first museum and art school founded in 1805. His classes, during the school seasons of 1919-1920 and 1920-1921, included classical life drawing and commercial training. The latter class “prepared students for careers as book and magazine illustrators,” a path Falk soon followed.

His teacher, Henry Bainbridge McCarter (1846-1942], promoted modernist art movements to his students.5 Before McCarter became the first teacher of illustration at PAFA, remaining there for forty years until his death, he was a PAFA student of Thomas Eakins. In the late 1880s, he studied in France at Beaux-Art de Paris and was an apprentice in lithography to Toulouse Lautrec. Upon returning to America, McCarter drew illustrations in New York for magazines (e.g., Harpers, Scribners. McClure’s, Colliers) before focusing on prize-winning ethereal landscapes in oil and watercolor.

McCarter surely encouraged his students, including Falk, to learn the craft of art-making, and appreciate modernist art as an enrichment of their lives. In the spring of 1920, 25,000 visitors viewed PAFA’s “Representative Modern Masters,” the first of three landmark exhibitions in the history of American modernism that included works by Cezanne, Gauguin, Picasso and Matisse). Philadelphia Orchestra director Leopold Stokowski wrote the catalog’s introduction, encouraging acceptance of modern artists by comparing them to Debussy and Stravinsky. In 1921, PAFA presented “Later Tendencies in Art” featuring nearly 100 modernists (Stella, Hartley, Marin and others).6

Falk’s progressive art education at PAFA was important but brief, as he needed to help with his family’s finances. He worked as an art director for Gimbels in Philadelphia, but also freelanced drawing illustrations, advertisements and book covers. At the end of two years in Philly, Nat decided he’d “had enough and went back to Baltimore.”

“He got very sick,” Karen Falk said. “I remember Grandma telling me he was working all hours.” Grandma was Katherine Sagal (1901-1993), who was born in Kharkov, Russia. In the 1920s, she worked in the personnel department at the Baltimore Gas & Electric Company. Nat moved to New York in about 1923, and Katherine joined him when they got married in 1925. The couple had two children: Stanley L. Falk (b.1927), who became a military historian/author and David S. Falk (1932-2020), who became a physicist/author.

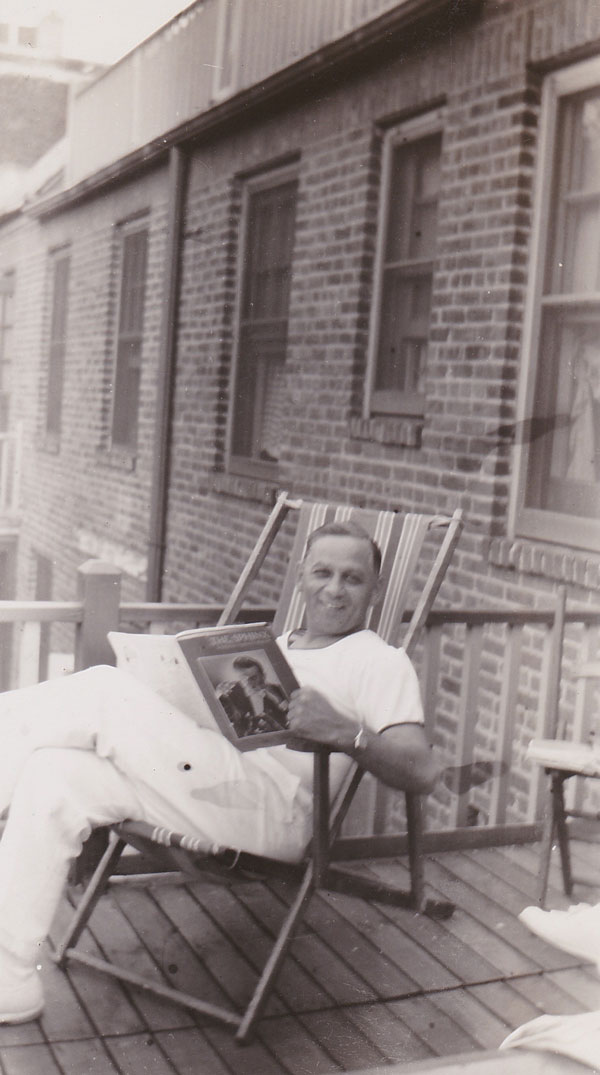

Shortly before their second child was born in 1932, they moved from the Bronx to a small two-story row house in Sunnyside Gardens on 46th Street in Long Island City. “It was one of these special places they started up, with a big garden area out in back,” recalled their son Stan. “There was plenty of room then, and we played in the streets because there wasn’t much traffic, if at all. That was good. And we could get the subway and get to town in 32 minutes. Two blocks from the subway. We lived on the second floor, and there was a finished attic, and that was his studio. Dad worked there.”

Dad was a busy freelance artist, seeking and juggling illustration and advertisement jobs, writing assignments, making contacts and becoming friends with many of them, keeping up with what was happening in the popular and fine arts, and managing to keep his family afloat. “I always admired how he kept us reasonably well-fed,” his son noted. “We always thought he was a slow man with the buck, but he had reason to be. How he did it with freelancing. When you freelance you never turn down a job! He’d be working all the time at home.”

Occasionally, Nat took his family to Broadway shows. “He wanted to show off what a fine actor Paul Muni was,” Stan recalled. “He would take me to see a magician, such as Blackstone. Or Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson doing his famous tap dance. My father was a link to theatre, my mother was my link to opera.”8

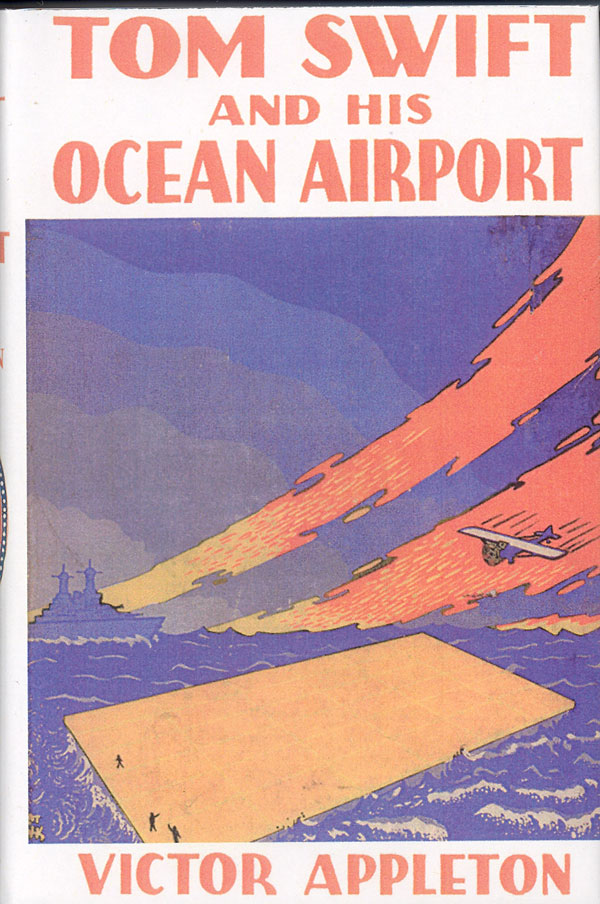

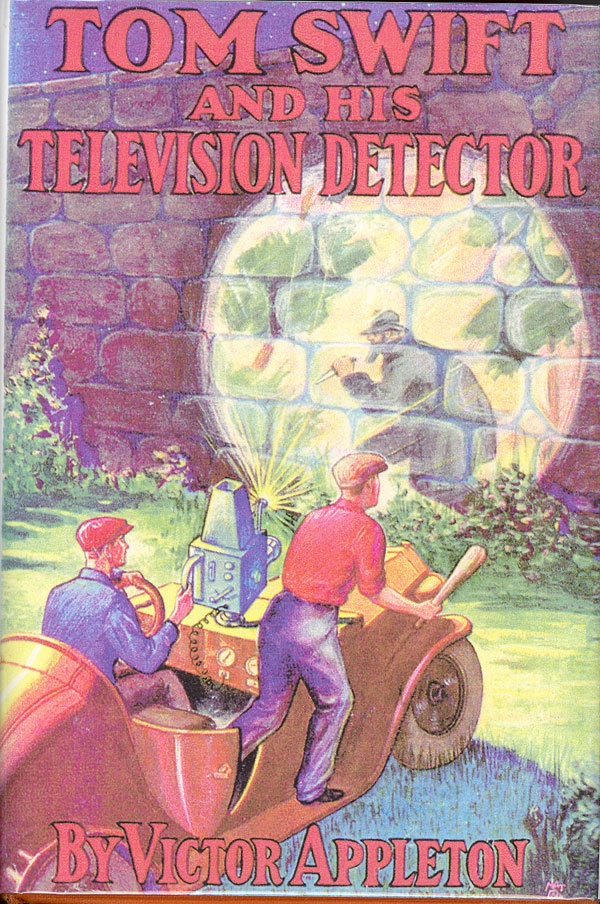

In the 1930s, Falk illustrated a steady stream of book covers (click link to view selection) and interior illustration jobs, including two popular long-running juvenile hardback series: Tom Swift, and Don Sturdy. (The wild mechanical inventions of the Swift books, such as Tom Swift and the Electric Magnet (1932), had a wide audience, attracting even the admiration of Dada artist Marcel Duchamp.)7

In a 1932 exhibition at the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, Falk’s art was shown alongside book jackets by Rockwell Kent, Wanda Gag, and Diego Rivera, among others. “The museum had hundreds of jackets submitted to it,” reported the San Francisco News, “and picked the most unusual.”9 Click here to view news story.

Falk’s book covers display great versatility and imagination in the styles he conjures in layout compositions, typography, unusual color choices and draftsmanship. The subject matter ran the gamut from crime biographies (Red Hell, 1934) to western novels (Tenderfoot Trail, 1936); racy pulp novels (Twilight Men, 1931), Lady Chatterley’s Husbands (1931) to how-to manuals (Taking Trout with the Dry Fly, 1930), Charles’ Book of Punches and Cocktails, 1934).

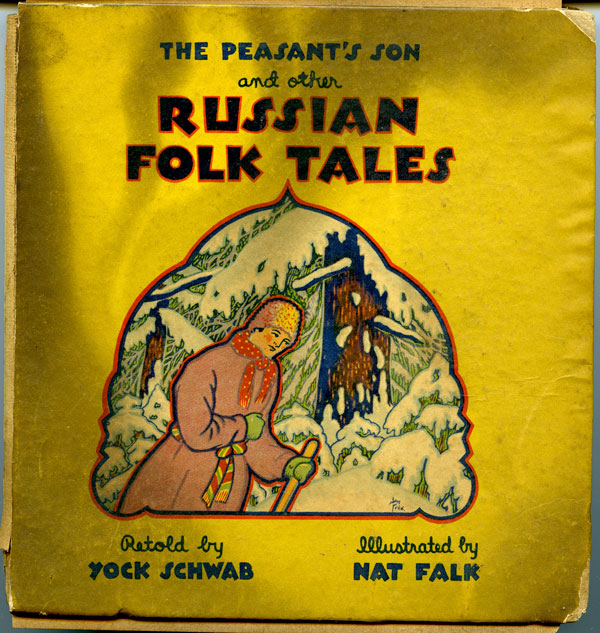

In 1933, Falk charmingly illustrated Magic Mother Goose; in 1934 he used a woodblock style for Russian Folk Tales, written by his friend Yock Schwab. In 1938, he drew a syndicated informational strip, “What Do You Know About Health?”10

At one point he took on advertising jobs for MGM Studios and the Roxy Theatre, where he sometimes worked in a small downstairs office. “I’d go down to see him,” said Stan, “and get to see free movies.”

How he came to write a book on animation history and production processes is not known. He wasn’t an animator nor a storyboard artist, though his draftsmanship and writing skills indicate he could have succeeded in both of those paths. Family members suggest that his openness toward meeting and becoming interested in people, particularly artists and their work, explains his friendship with early animation producer Paul Terry: “My grandpa said he used to go up to Terry’s studio in New Rochelle and hang out,” Karen Falk said.

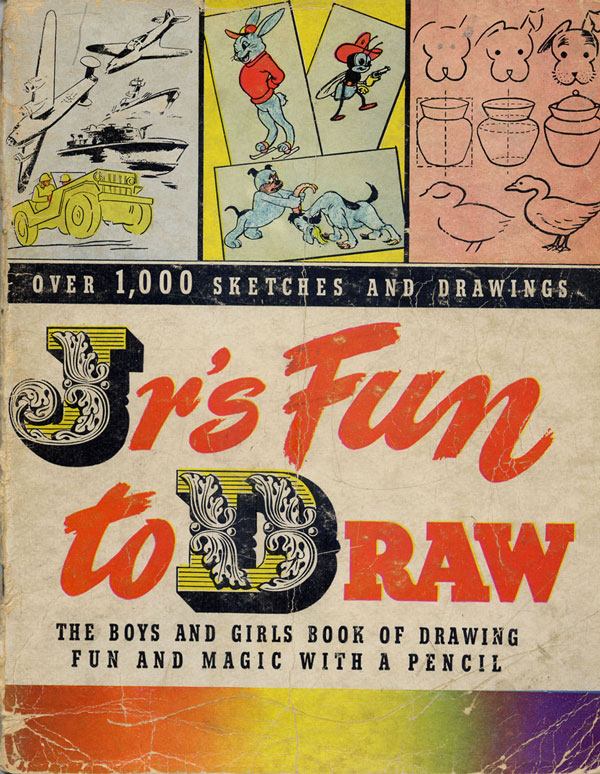

Two years after How To Make Animated Cartoons was published, Falk compiled and wrote an animation section for a “companion” booklet by Alan Dale Bogorad:

Jr’s Fun to Draw – The Boys and Girls Book of Drawing Fun and Magic With a Pencil (1943).

Again, Falk obtained permission to use famed cartoon characters for illustrations from Terry, Leon Schlesinger and Paramount Studios. In 2009, Jerry Beck, the estimable animation/comics historian, posted the Falk section of this rare paperback on CartoonBrew.com 11

Falk continued freelancing as an illustrator, and then, as publishing work dried up, he moved into art direction at ad agencies. Came a day in 1953, however, when he found himself out of work at age 55. Katherine, his wife, quickly took up the financial slack by getting a job in an employment agency. “Pretty soon,” Stan said, “she figured out the way to make money was not to work for somebody else, but to set up your own. So, she started her own business, Falk Personnel. Became a management consultant in the temp employment area and did very well. A lot of big companies used her services.”

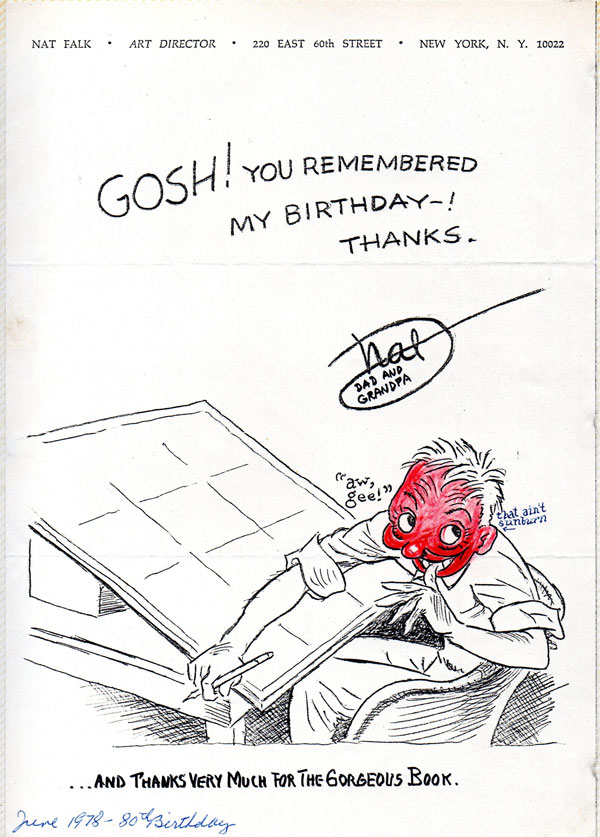

Karen Falk remembers it became a family business: “Grandpa would do all the layouts for the job advertisements. He would work them up and she’d submit them to the newspapers for the jobs. So, he supported her business when it started.” Katherine, who loved working, finally sold the business and retired twenty-five years later (“kicking and screaming,” her son Stan recalled) when she was 77 and Nat was 80.

By that time, Nat and Katherine were living on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, doting on their grandchildren, Karen, her sister Lisa, and their cousins Birgit and Sam. In retirement, Nat Falk continued his keen interest in all areas of art and passed it on to his granddaughters and their children, clipping Lord and Taylor ads and Al Hirschfeld caricatures to interest them in graphic design.

An avid museum-goer, Falk became fascinated by a 1982 exhibition of Nam June Paik’s video art at the Whitney Museum. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, admiring a painting by Robert Henri, author of The Art Spirit, Nat casually referred to the artist as “old Bob Henri,” one of his lecturers at PAFA.

Nat Falk was the epitome of a freelancer who survived by never turning down a job, a situation that many artists and animators today can relate to. Though his primary goal was to support his family, Nat Falk inadvertently became an educator as well. He “taught” a variety of topics through many of his commercial art jobs, and with How to Make Animated Cartoons, he found at least one avid student in me.

NOTES

- Karen Falk and Stanley (Stan) Falk. Zoom interview with John Canemaker, 01 Sept. 2022. Quotes are from this interview unless otherwise noted.

- 1918 pop song “Can You Tame Wild Women?” by Andrew B. Sterling, music: Harry Von Tilzer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IuHloG8xx_w

- Karen Falk and Stan Falk email to author, 11 September 2022.

- The American Jewish Chronicle, Aug. 24, 1917, p. 437.

- PAFA archivist Hoang Tran to Karen Falk, eMail to author, 29 August 22; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Bainbridge_McCarter

- https://pafaarchives.org/page/timeline?utm_source=PAFA&utm_medium=referral

- Marcel Duchamp interest in TOM SWIFT books. https://www.toutfait.com/a-very-normal-guy-an-interview-with-robert-barnes-on-marcel-duchamp-and-atant-donnas/’

- Paul Muni appeared often on Broadway, e.g., in 1940 he starred in Key Largo; in 1939, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson appeared in The Hot Mikado on Broadway briefly and then for two years at the New York World’s Fair.

- “The Jacket Makes the Book.” The San Francisco News (April 16, 1932)

- 4, 1938 Andover News (NY), p. 7: What Do You Know About Health? by Fisher Brown and Nat Falk.

- Jr’s How to Draw – The Boys and Girls Book of Drawing Fun and Magic With a Pencil by Alan Dale Bogorad. <https://www.cartoonbrew.com/books/jrs-fun-to-draw-11257.html>

Copyright © John Canemaker, 2022. All rights reserved.

Hits: 714