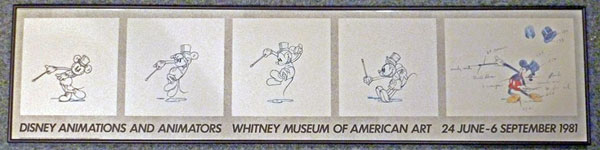

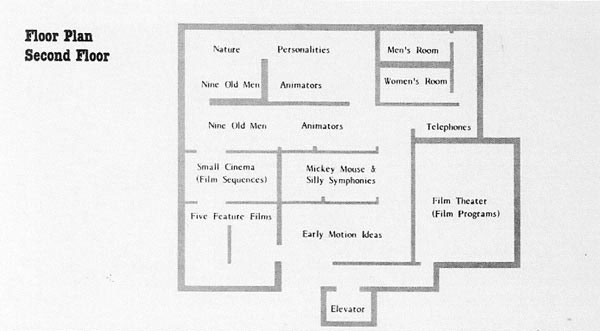

Today, I’d like to set our Time Machine back nearly four decades, for a visit New York City’s Whitney Museum of American Art from June 24 through September 6, 1981, and its grand, large-scale exhibition titled “Disney Animations and Animators.”

But first, a little context.

Disney animation exhibitions had been occurring in art museums and galleries well before 1981.

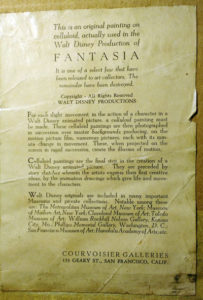

In 1938, Guthrie Courvoisier, a fine art dealer in San Francisco, signed an agreement with Walt and Roy Disney granting him exclusive rights to market their original animation art. Original Disney Studio art sold through the Courvoisier Gallery came with a certificate that emphasized the authenticity and the select nature of the works being sold.

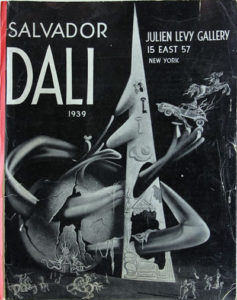

Through the efforts of Courvoisier, the prestigious Julien Levy, who presented the first exhibition of Surrealism in New York, was one of the first to exhibit Disney’s work in a commercial gallery. He offered the “First National Showing of Original Watercolors from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” from September 15 through October 4, 1938.

From March 21 – April 17, 1939, Levy presented “Original Watercolors on Celluloid Used in the Filming of Walt Disney’s Ferdinand the Bull.” On April 8 – 23, 1940, modernist Levy, who also exhibited films including Disney’s in conjunction with exhibits, presented “Original Watercolors for Walt Disney’s Pinocchio.”

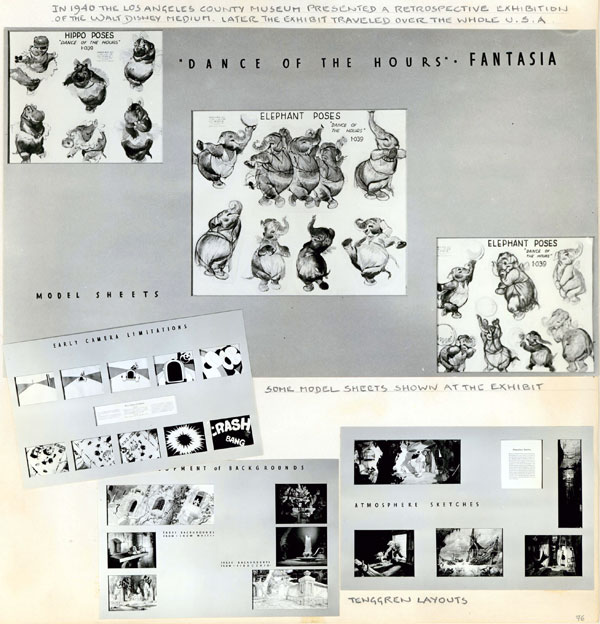

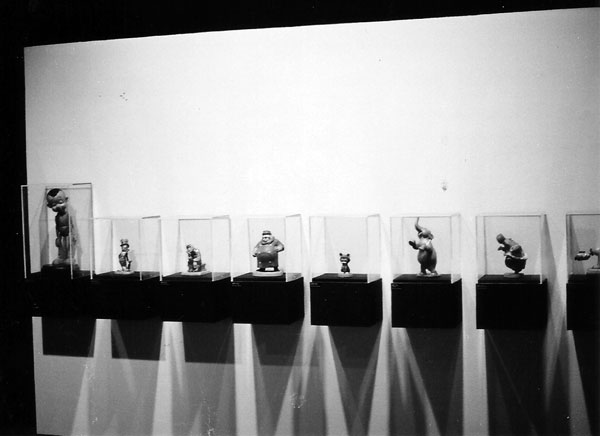

Also in 1940, the Los Angeles County Museum’s director, Roland J. McKinna, arranged the first overview of Disney’s contributions to animation, “a new art form” from Steamboat Willie (1928) to Fantasia (1940). This early retrospective exhibition, a merging of high and popular art in a museum setting, revealed the artistic processes of animation through preliminary concepts sketches, story drawings, cels, backgrounds, model sheets, and maquettes. “In twelve years,” McKinney wrote in the exhibition catalog, “Walt Disney has elevated animated pictures from a crude form of entertainment to the dignity of a true art.” After Los Angeles, the exhibit traveled to seven museums across the country ending in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Back in New York, the Galerie St. Etienne, which specializes in Expressionism and Self-Taught Art (the Galerie gave Grandma Moses her first one-woman show in 1940) exhibited “Walt Disney Originals” starting on September 23, 1942.

On December 9, 1943, they presented a “Walt Disney Cavalcade”; and, on October 28, 1949, an exhibit simply called “Walt Disney.”

In 1958, I was a 15-year old Disney film fan, and I remember (with great nostalgia) visiting “The Art of Animation! A Walt Disney Retrospective,” a traveling exhibition that was basically a promotion for the upcoming animated feature Sleeping Beauty (1959).

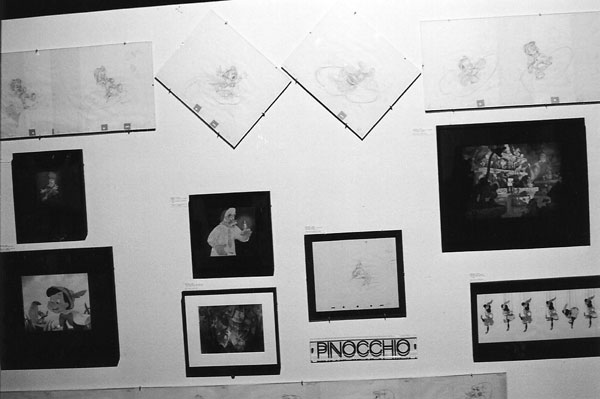

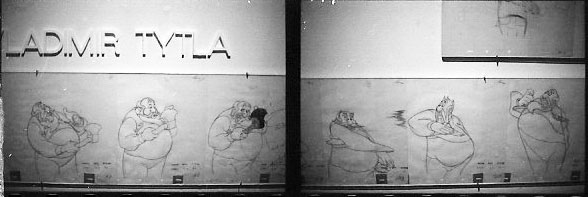

I begged my parents to drive me from Elmira, New York to Rochester. They indulged me, and I remain grateful. For what I saw — original cels and backgrounds, animation drawings, concepts from Sleeping Beauty and a slew of other films, including, as I fondly recall, the Disneyland TV program Mars and Beyond (1957) — continued to inspire me years later when I curated animation art exhibitions at the Katonah Museum (Winsor McCay; Vladimir Tytla) and the Walt Disney Family Museum (Mary Blair; Herman Schultheis; the art of Pinocchio).

Common to all of the above mentioned animation art exhibitions held during Walt Disney’s lifetime (he died in 1966) was that he received exclusive credit for what got onto the screen. The army of artists he employed were, for the most part, anonymous. The 1981 Whitney Museum of American Art’s “Disney Animations and Animators” exhibition changed all that.

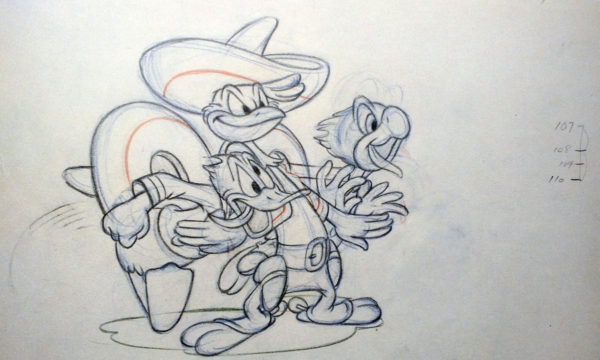

In this high art venue, individual animators were named alongside drawings that they created. Specific animators were cited (e.g. Ham Luske, Vladimir Tytla, Fred Moore, Art Babbitt, and each of the so-called Nine Old Men, among others) for their special (nay, extraordinary) contributions to iconic Disney scenes; including crediting their participation in codifying essential animation principles, which certain animators either pioneered or developed to sublime expressive heights.

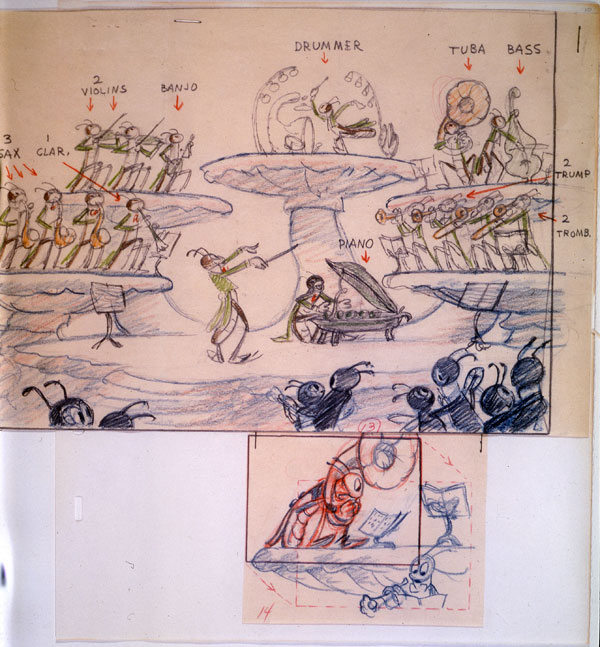

The exhibition also offered artwork from every phase of production – concept sketches, layout drawings, storyboards, background paintings — and their artists (where known) also received credit.

Greg Ford, the highly respected animation historian, film producer and director, was Guest Curator of this spectacular show of the Disney studio’s creative process.

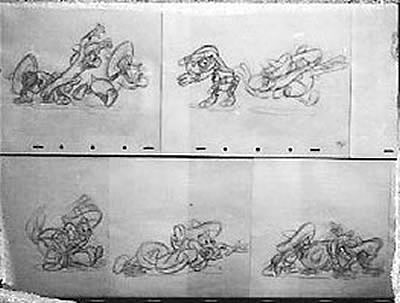

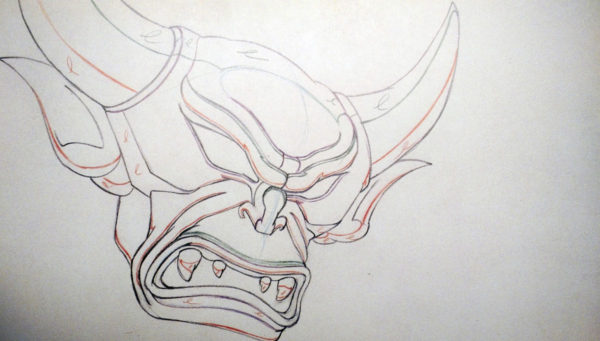

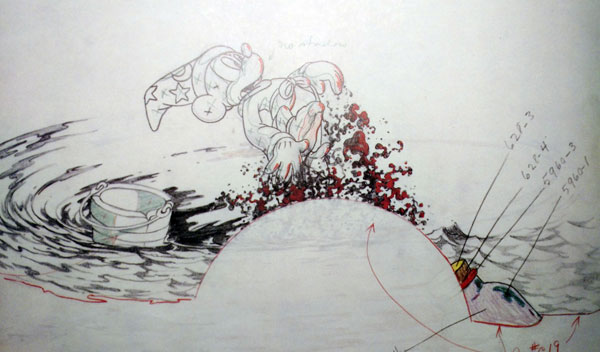

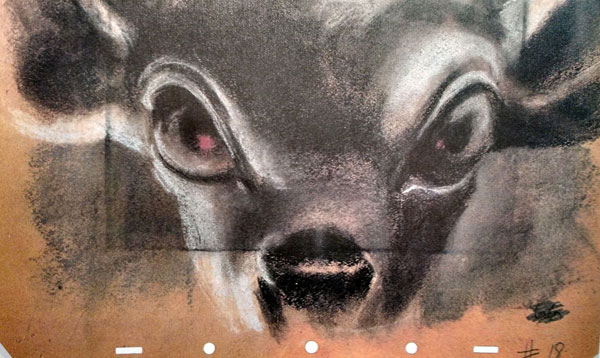

Ford’s selective connoisseurship focused on animation drawings — their wild, single-frame exaggerations necessary to make visual points read loud and clear to the audience; the use of space as a compositional element; the choreography involved in working out a gag or a dance; razor-sharp storytelling clarity seen in a flurry of sequential main pose drawings, a.k.a. “extremes.” And he specified who did what.

“Disney character animation represents the most successful and sustained realization of a world within the film frame,” wrote John G. Hanhardt, Whitney Museum’s Curator of Film and Video at the time.

Greg Ford’s selection of works highlights the drawings as discrete items and as part of a process. The process concludes in the film projected onto the screen, and many of the most important Disney short films and features are being shown as part of this exhibition. In addition, throughout the galleries videotape monitors present individual sequences, which illustrate the animation process. From this exhibition we can look again at the films and recognize familiar faces and actions — and appreciate what a rich and provocative body of drawings and film art Disney animations are.

To give you a flavor of the show, and how it was mounted, are black and white photographs that I shot on assignment as a contributing editor for Print magazine. (Print eventually published an article I wrote on “Disney Backgrounds” in the March/April 1982 issue, based on artworks in the Whitney exhibit.) I’ve also included a handful of color images of some of the art exhibited, with apologies for the poor quality of the black and white shots, which were taken in available light for reference purposes only.

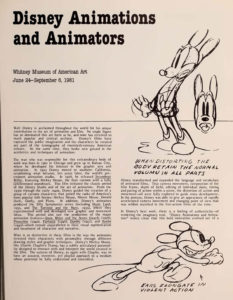

Unfortunately, no illustrated catalog accompanied the exhibition; but in a concise, informative six-page handout John Hanhardt discusses the exhibit, and it contains all the films screened during the show’s run. Click the image at left to read a full-size copy and turn the pages.

Unfortunately, no illustrated catalog accompanied the exhibition; but in a concise, informative six-page handout John Hanhardt discusses the exhibit, and it contains all the films screened during the show’s run. Click the image at left to read a full-size copy and turn the pages.

In 1982, a goodly number of the artworks from the Whitney exhibition found their way into Treasures of Disney Animation Art, publisher Robert Abrams’ giant (16” X 13”) Abbeville Press tome. I wrote the book’s Introduction, concluding:

Herein is contained a small but delicious sample of the huge amount of research, analysis, and preparation that contributed over the years to Disney’s film accomplishments. The body of work, remarkable in its own right, is a tribute to the visionary power and leadership abilities of Walt Disney, and to the individual talents of his staff of artists and craftspeople [emphasis added], whose cumulative efforts made the visions real.

Hits: 9839

John! What a wonderful article you have written. I never knew that Disney art, in all of its varieties, was exhibited at the beginning of the Golden years. I knew of Courvoisier, and the coveted status of their cels today, but not of their efforts in supporting exhibitions. Your story of childhood warmed my heart (I’m sure your fifteen-year-old self wished you could be a part of all that someday). I’m grateful for you, John, and everything you have contributed to animation history. This piece is just another example of that. Thank you for continuing to inspire and enlighten us all!

Thanks for bringing this exhibit into the light once again! I remember staring in disbelief at the color cel setup of the head and shoulders of the Evil Queen from Snow White: every group of hand-inked lines on the top cel was colored to accent the shapes they enclosed. Her eyelids were lavender, her throat was warm brown, her headdress deep blue and violet, her lips crimson red. They must have been painted with a very fine brush, each one varied in width along its path, using thick-to-thin techniques to emphasize roundness, nearness or depth from the picture plane. This portrait was perfection in craft to me, a new ink-and-paint artist in New York in 1981. I slowly realized that if every cel of Disney’s films were made like this one, the work that went into these wonderful films was truly monumental!

In 1978, before the Whitney show, there was a more modest exhibition at the fledgling Drawing Center in Soho: Drawings for Animated Films 1914-1978. Lots of Disney drawings, as well as Fischinger, Fleischer, MGM, Lantz, Hubley, all intermingled with work from contemporary, independent animators: Breer, Rose, Faccinto, Protovin, Beams, et al. It was curated by Marie Keller; the catalog included an essay by a young animator also in the show, John Canemaker.

The first exhibition of Disney animation art, “Walt Disney, Creator of Mickey Mouse,” ran from Oct. 22-Nov. 6, 1932 at the Philadelphia Art Alliance. According to the Art Alliance Bulletin, “The pictures and films come to us through the courtesy of Mr. Walt Disney, the David McKay Publishing Company and the moving pictures through the courtesy of the Parkway Baking Company.” (This was before the studio’s association with San Francisco-based Courvoisier Galleries for the marketing of its original art.)

Between 1932 and 1949, Disney production art was exhibited (and often sold) at least 64 times at dozens of different museums, galleries, and libraries, in the U.S., England, Northern Ireland, and possibly Toronto, Canada. The Kennedy Galleries and Julien Levy Gallery, both in Manhattan, hosted Disney exhibits several times during that 17-year period.

It was, I also believe, through the auspices of Julien Levy, that Walt Disney presented a cel setup of the vultures from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That object is illustrated in my book, “Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit” (2015). The text of a booklet, “Notes on the Art of Mickey Mouse and His Creator Walt Disney,” by Eleanor Lambert, published to accompany a traveling exhibition organized by the College Art Association in 1933, appears in my anthology, “A Mickey Mouse Reader” (2014). Eleanor Lambert is now remembered as the founder of the International Best Dressed List and New York Fashion Week.

Incidentally, for a while in the 1940s, Walt was on the board of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.