Since the year 1305, visitors to the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, Italy, are also entering a 14th century movie palace. On the chapel’s walls and ceiling a favorite Biblical epic, The Story of Mary and Christ, unfolds its narrative in a sequential series of compelling, innovative frescoes, which are among the most important breakthroughs in western art. They were created by the great Florentine master designer, painter — and, yes, director/animator –Giotto di Bondone (1266/67 – 1337).

Giotto had an intuitive genius for visual storytelling and connecting emotionally with his mostly illiterate audience. In his hands, the story’s characters look and act like real humans. They live in familiar-looking Italian hills, houses and meadows; they communicate directly with viewers, make them participant’s in the story. Viewing the paintings becomes a shared, immersive experience.

This was a profound change from Byzantine symbolism. Those remote, expressionless, cord-of-wood figures floating on gold backgrounds are beautiful, but cold and distant imagery compared to Giotto’s work. By contrast, his paintings are mirrors of the human condition. A farmer’s son, he plowed the field, as it were, of modern representational art for key figures of the High Renaissance, such as Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci; the latter artist, born over 100 years after Giotto died, once remarked that post-Giotto “art declined.”

Always impressive is Giotto’s staging of scenes containing multiple figures. Unerringly, with great clarity, he focuses our eyes like a movie director. His “actors” express a wide palette of emotions, among them love, hate, horror, anger, fear, pity and sorrow. It’s all there, expressed with subtle economy and understatement in the poses and staging. Giotto’s art is truthful and, therefore, believable. Or “sincere,” the word older Disney animators used to describe sensitive character animation.

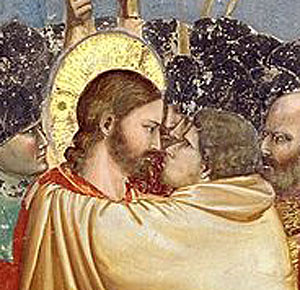

A superb example of Giotto’s gifts is the “Kiss of Judas” fresco depicting the moment just after Christ is betrayed to the arresting soldiers by an identifying kiss from Judas Iscariot, one of Christ’s apostles. The scene takes place in the midst of a swirling, unruly mob whose spears, halberds and torches serve as directional arrows pointing toward the two men at the center. The embracing folds of Judas’ yellow cloak — the color a psychological tell for his cowardly act — lead our eyes toward an affecting “close-up” of Jesus and Judas.

Jesus’ expression is calm, compassionate, forgiving, as he gazes directly into Judas’ eyes. His betrayer, by contrast, shorter or lower in position, appears to be frozen with guilt. His eyes sink into his furrowed, simian-like brow; his lips are still puckered. He is locked in fear and self-loathing. Amidst noisy turmoil, the stare between the two men is quiet; a surreal, slo-mo, time-stopping moment of private thoughts.

Jesus’ expression is calm, compassionate, forgiving, as he gazes directly into Judas’ eyes. His betrayer, by contrast, shorter or lower in position, appears to be frozen with guilt. His eyes sink into his furrowed, simian-like brow; his lips are still puckered. He is locked in fear and self-loathing. Amidst noisy turmoil, the stare between the two men is quiet; a surreal, slo-mo, time-stopping moment of private thoughts.

The Scrovegni fresco “cinema” also offers romance and a full-on, physical expression of love. When Joachim and Ann (parents of the Blessed Mary) embrace each other after months of absence, their eyes and lips lock as their hands tenderly and passionately pull each other close.

For on-screen horror, few blood-and-guts film scenes can compete with Giotto’s shocking fresco of the Slaughter of the Innocents: babies torn from their agonized mother’s arms are slaughtered by King Herod’s goons, amid a pile of massacred children.

For on-screen horror, few blood-and-guts film scenes can compete with Giotto’s shocking fresco of the Slaughter of the Innocents: babies torn from their agonized mother’s arms are slaughtered by King Herod’s goons, amid a pile of massacred children.

Giotto also possessed a sense of humor and wasn’t shy of displaying comic relief in otherwise serious contexts. Observe the scene-stealing, braying camel that startles its handler in the “Adoration of the Magi” fresco.

Giotto also possessed a sense of humor and wasn’t shy of displaying comic relief in otherwise serious contexts. Observe the scene-stealing, braying camel that startles its handler in the “Adoration of the Magi” fresco.

The artist’s personal humor endeared him to his friends. He was said to be a homely man, and legend has it that Dante (who apparently had no filter) once asked Giotto how he could create such beautiful paintings and such ugly children. The artist allegedly replied: “I make my pictures by day and my babies at night!”

Can today’s animators and filmmakers still learn from an artist who lived more than 700 years ago? Of course! One can always profit from analyzing Giotto’s visual communication techniques. I contend that Albert Hurter did precisely that in Walt Disney’s first feature, SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS (1937).

An excellent draftsman, Hurter (1883-1942) arrived at the Disney studio in 1931 at age 48 with an extensive background in fine arts training and study in Europe. With his encyclopedic knowledge of art history, he often regaled his cartoonist colleagues with descriptions of the art of Vincent Van Gogh, Herman Vogel, Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, Franz Stuck, and Heinrich Kley, among others.

An excellent draftsman, Hurter (1883-1942) arrived at the Disney studio in 1931 at age 48 with an extensive background in fine arts training and study in Europe. With his encyclopedic knowledge of art history, he often regaled his cartoonist colleagues with descriptions of the art of Vincent Van Gogh, Herman Vogel, Honoré Daumier, Gustave Doré, Franz Stuck, and Heinrich Kley, among others.

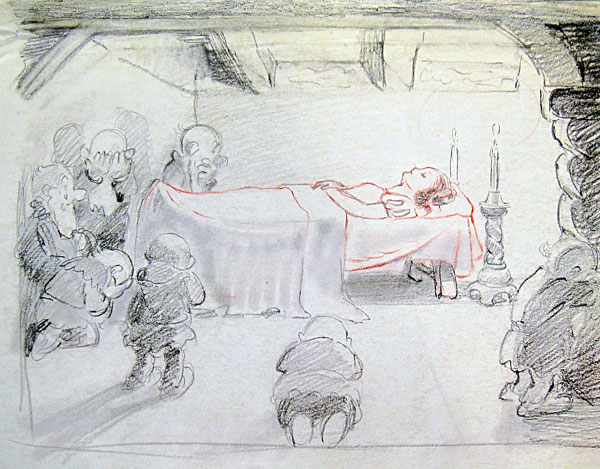

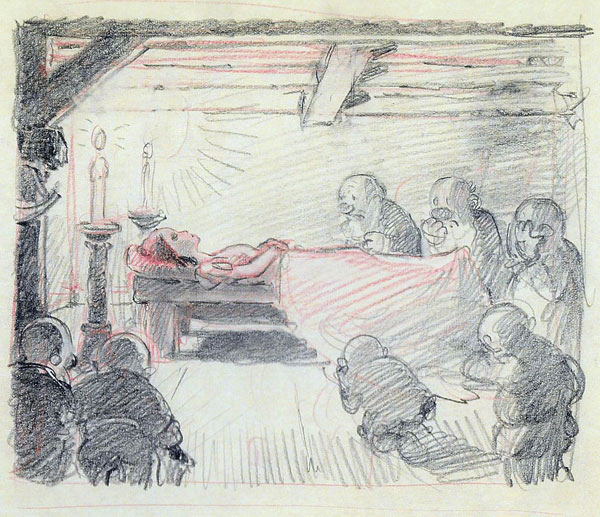

Hurter became the Disney studio’s first “inspirational sketch” artist: he created hundreds of imaginative conceptual drawings, ideas for personality gags and visualizations that would inspire the studio’s directors, writers, storyboard artists and animators. In SNOW WHITE, his visual influence is all-pervasive. Of particular interest is a sequence that is a breakthrough in the art of character animation: the seven dwarfs grieving over the inert body of Snow White.

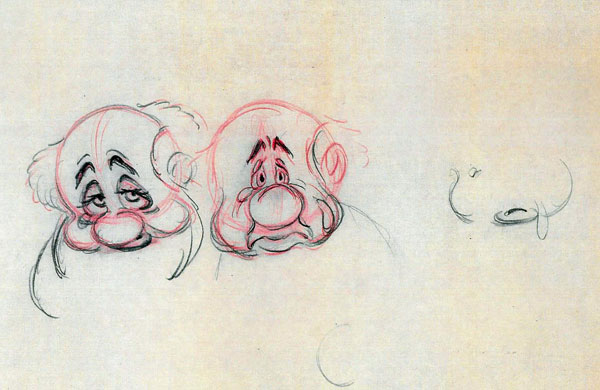

For Walt Disney, it was a daring gamble. For he hoped audiences would suspend their disbelief to find believable the emotions expressed by cartoon characters mourning the “death” of another toon. In dozens of sketches, Hurter relentlessly searched for the right body language and facial expressions for the dwarfs as well as suggestions for positioning the characters around the bier within a cottage setting, ideas for lighting, mood and so on.

His creative search, to my mind and animated eye, was similar to Giotto’s process in creating the Lamentation fresco in Scrovegni Chapel. It is reasonable to assume that Hurter, art history maven, knew of and may have found useful, the composition and gestures of the 14th century master’s painting. Giotto’s brilliant placement of individualized mourners, each grieving in their own way — quietly mournful to hysterical disbelief — as guideposts, leading our eye to the prostrate Christ embraced in his mother’s arms. Above, ten angels mirror the scene, and they behave in distinctively individual mourning poses and expressions, too.

Similarly, Hurter’s dwarfs each display sorrow in seven distinct ways: staring in disbelief, weeping openly, some so distraught they avoid looking at the radiant princess’ body, whose glow rivals the light emanating from the candles behind her.

When master animator Frank Thomas (1912 – 2004), with great subtlety, transformed Hurter’s idea sketches into animation drawings (see below), audiences wept at the final result.

As my friend, animation historian John Culhane, once said regarding Snow White’s lamentation sequence: “Moving drawings became . . . moving drawings.”

Hits: 3841

Thanks for this marvelous piece. I’ve been enjoying a book and documentary series, “Art Of The Western World,” that deals in part with Giotto, so your observations were timed just right, and very welcome. You also have a very pleasing design here — particularly like the banner.

Such wonderful insight and marvelous interconnections! I studied Giotto in college and your sharply focused piece brought his work back to me in a refreshing new way. Ditto for the seven dwarfs… Many thanks!

A lovely post. Phyllis and I visited the Scrovegni Chapel almost twenty years ago, and a return visit is part of my life’s unfinished business. The Disney parallel seems exactly right. The great Disney cartoons are distinguished by their simplicity and directness, and those are exactly the virtues that make the Giotto frescoes so powerful and moving.

Strangest of all, the most powerful way to experience the power of the Scrovegni frescoes is the way Hurter did — in reproduction. Sadly, the Chapel itself has become a somewhat grotesque tourist attraction. To protect Giotto’s work, visitors are decontaminated for 15 minutes and then enter the chapel in clusters, given another 15 minutes to look around while a tour guide talks into her mini-speaker. Your bravura connections, John, not only showed how to see Giotto’s art from a fresh perspective, the Scrovegni Chapel opens up broader questions of what it means to say, “I’ve seen that work.”

Very impressive and connection to “Snow White” a real eye-opener. Thank you for this excellent blog.