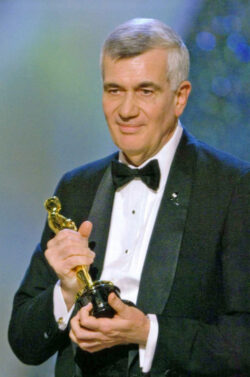

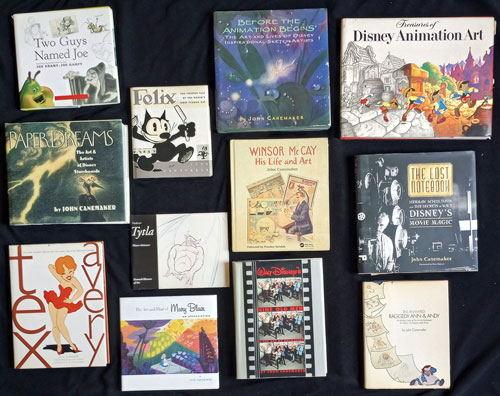

by John Canemaker

INTRODUCTION

By the time I became a teenager in 1956, my childhood interest in the history and techniques of animated films had become an obsession.

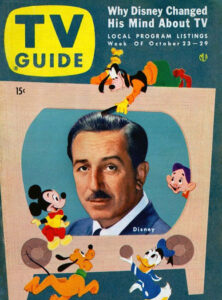

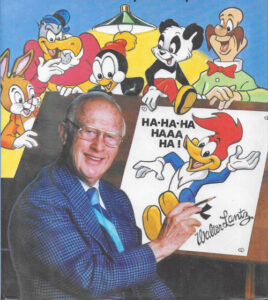

My initial curiosity was sparked by two television series: Disneyland (1954), hosted by Walt Disney, and The Woody Woodpecker Show (1957), hosted by Walter Lantz.

Occasionally, both of those rival film producers would demonstrate animation “secrets” about how-to make cartoon drawings move. One 1955 Disneyland episode, “The Story of the Animated Drawing,” introduced audiences to the earliest of film animators. Showcased among the pioneers of silent cinema was Winsor McCay (1867-1934), the genius comic strip cartoonist and pioneer animator, whose biography I would write three decades later.1

In my hometown of Elmira, New York, I scrambled for information on both the history of the art form and how to make my own cartoon film. At that time, books on animation techniques and its history were few; but they were informative and inspiring to someone searching for information.

Walt Disney – The Art of Animation by Bob Thomas, published in 1958, a lavishly illustrated tome promoting the making of Disney’s 1959 feature film Sleeping Beauty, included a small history section on pre-Disney animation.

Walt Disney – The Art of Animation by Bob Thomas, published in 1958, a lavishly illustrated tome promoting the making of Disney’s 1959 feature film Sleeping Beauty, included a small history section on pre-Disney animation.

Another source, Advanced Animation, illustrated by master animator Preston Blair, an iteration of his 1947 how-to manual on principles of Hollywood animated cartoons, is still in print.

From Britain, The Technique of Film Animation (1959) by John Halas & Roger Manvell offered tantalizing glimpses of international and avant-garde animation. I devoured each book while searching for more at local libraries.

From Britain, The Technique of Film Animation (1959) by John Halas & Roger Manvell offered tantalizing glimpses of international and avant-garde animation. I devoured each book while searching for more at local libraries.

At The Art Shop, a small store that sold artists’ materials and made picture frames, the kind-hearted owner Arthur Rosskam Abrams, an exhibited abstract painter and lecturer, encouraged my flipbook animation experiments, sequential drawings and persistent questions.2

An Art Shop store worker named Delos Smith generously gave me two older books on animation. One was a 1941 paperback edition of How to Make Animated Cartoons written by illustrator Nat Falk. It featured examples from animation producer Paul Terry’s Terrytoons studio in New Rochelle, New York, with a succinct section on animation history.3

An Art Shop store worker named Delos Smith generously gave me two older books on animation. One was a 1941 paperback edition of How to Make Animated Cartoons written by illustrator Nat Falk. It featured examples from animation producer Paul Terry’s Terrytoons studio in New Rochelle, New York, with a succinct section on animation history.3

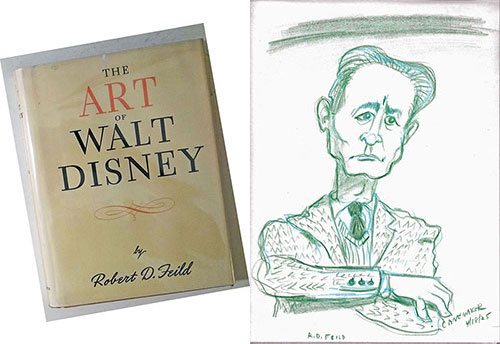

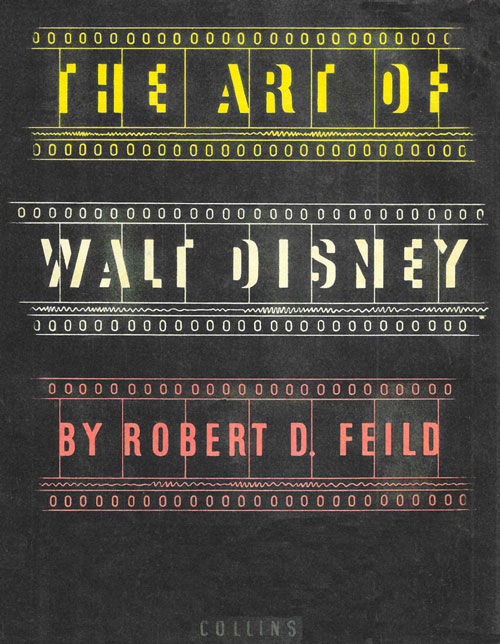

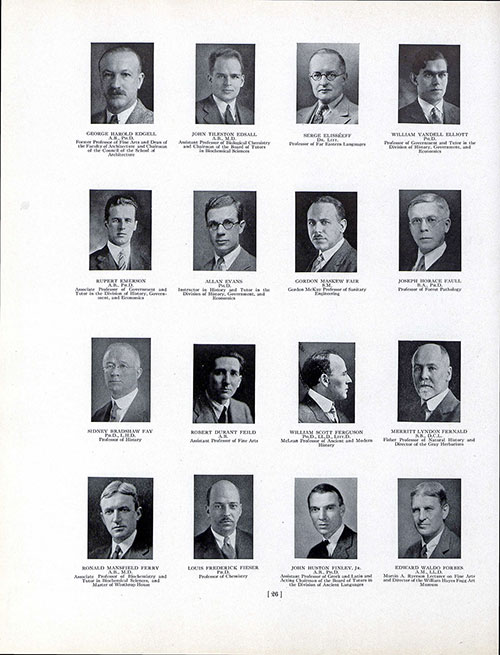

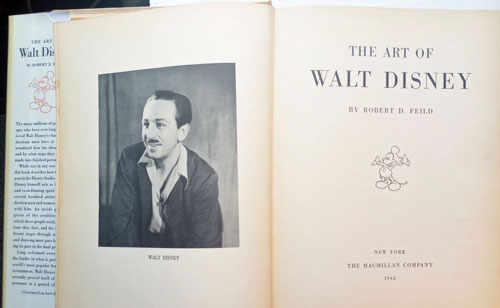

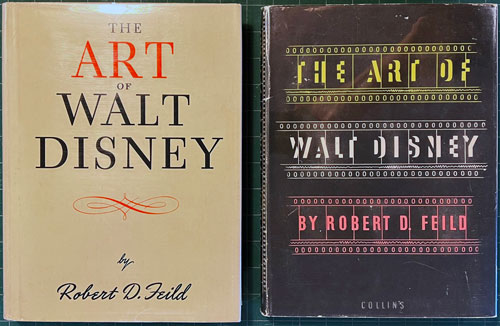

The other gift book was The Art of Walt Disney, written by Harvard art professor Robert Durant Feild, published in 1942. Both books proved to be illuminating; but Feild’s was the first serious in-depth analysis in book form of the Walt Disney Studio’s contributions to the development of character (or personality) animation.

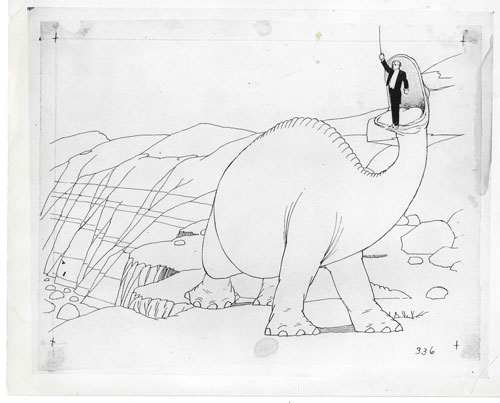

This indigenously American type of animation was first explored by Winsor McCay in his early silent films, How a Mosquito Operates (1912), and Gertie (the Trained Dinosaur) (1914). McCay’s mosquito and dinosaur were the first film cartoon characters to display naturalistic weight and, most important, distinctive personalities.

Gertie, for example, is a huge diplodocus who acts like a petulant little girl. Her unique persona is revealed by the way she moves. Audiences empathize with her pantomimic emotions, be she inquisitive, bad-tempered, disobedient or a shamed crybaby.

McCay set a high bar for animators. For years, his extraordinary draftsmanship and illusion-of-life animation would not be emulated or surpassed until the Walt Disney Studio’s Golden Era in the mid-1930s.

“I want characters to be somebody,” Walt Disney said in 1927. “I don’t want them just to be a drawing!”4 Disney‘s artists built upon McCay’s art by analyzing and codifying principles of motion and visual communication. They established their own animation art school at the Disney Studio to refine draftsmanship, explore design, color, soundtrack technology, cinematography and staging. To the animated cartoon, they applied stylistic conventions of live-action films, with emotions and motions derived from a character’s personality.

In 1939, Professor Robert D. Feild received permission from Walt Disney himself to spend nearly a year exploring the Disney Studio in Hollywood. The engagement offered rare access for a serious study of the studio’s innovative methods of film production, to ultimately be presented in book form.

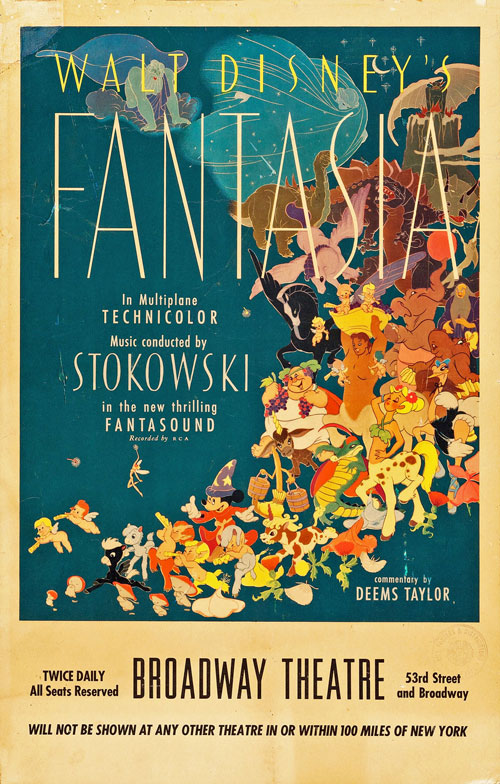

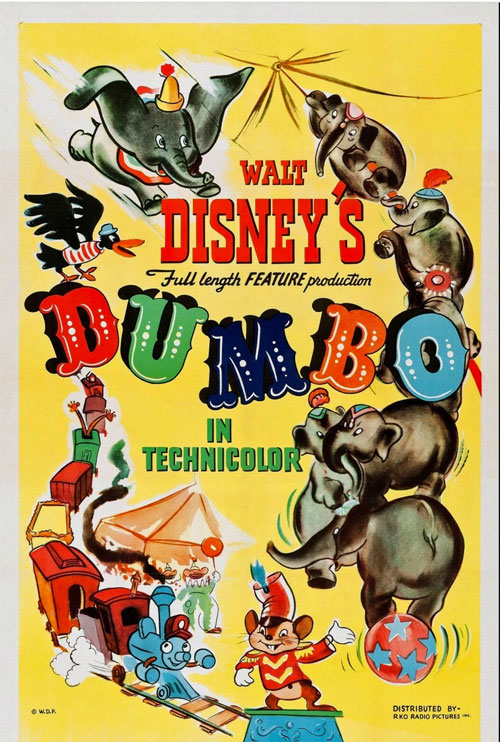

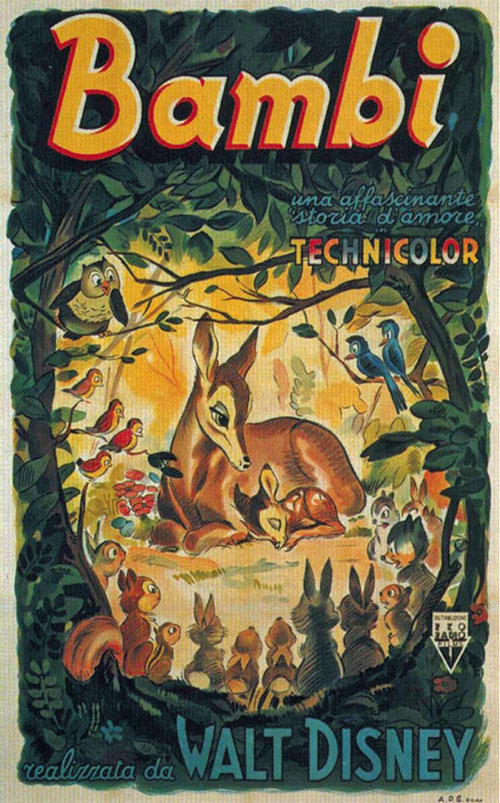

His assignment took place in a brief sliver of time, before World War II profoundly changed everything. Feild became an articulate eyewitness during the making of the now-classic feature-length animated films Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi — arguably, the peak creative period in Disney’s history. The Disney Studio, which celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2023, was only nineteen years old when Feild’s The Art of Walt Disney was published by The Macmillan Company in 1942.

Feild was a fine arts professor open to and passionate about modern art, including movies. “The animated sound picture,” he wrote, is “the most potent form of artistic expression ever devised to evolve beneath our eyes . . . Fantasia is no more an animated cartoon than the Stanze of the Vatican are comic strips.”5

Feild’s deep dive research into Disney’s animation moviemaking was meticulous and probing; his elegant, witty writing is scholarly, yet highly readable. Revelatory, too, are the color and black-and-white illustrations he chose to inform the text.

In his championing of the animated film, a relatively recent art form that merges traditional artforms with science, Feild was a rebel challenging the high/low art divisiveness of the period. He eloquently argued that storytelling continues to regale humankind, “ever since the first story-teller called forth images in another’s mind. Only the technique is different. Now the painted picture, the movie camera, the animated cartoon, drama and stagecraft, choreography, and music make their contributions . . . And through a magic made possible by thousands of years of experimentation, we have once again fallen under the old spell.”6

Professor Feild proved to be the right person at a special time to research, analyze and discuss the creative processes of films considered today to be animation masterworks. However, his research and ardent admiration of Disney films cost him his position at Harvard. And although Feild enjoyed researching the book at the Disney studio, its writing phase was stressful.

First, he first had to learn and organize a myriad of technical production details from many artists and artisans; then, accommodate the demands for text changes from studio fact-checkers, the publisher and Walt Disney himself.

An exhausted Feild confided to a friend after The Art of Walt Disney was finally published

There was something more to it than writing a book! There was more to it than art or Walt Disney — there was so much mess from time to time that it’s a wonder that the book ever got itself between covers. In fact, I’m amazed the darned words didn’t eventually come out backwards, and the plates get smooched with blood and sweat and tears!7

Nevertheless, Feild’s book became, and remains today, an important source of firsthand knowledge about the making of Disney film artworks in an early important period of their development.

Through the years, the Disney book has inspired countless animators, and also writers on Walt Disney and animation history. When I wrote my animation history books, the format and content of Feild’s The Art of Walt Disney were often borne in mind. Particularly the author’s passion for the subject, his wit and professorial detailed approach to explanations, and choice selection of photos and illustrations to add clarity to the text.

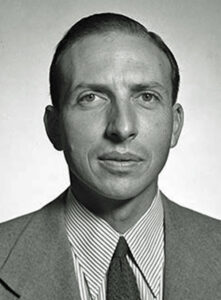

I have often wondered who Robert Durant Feild was, his background and creative processes in teaching about the art of animation, and particularly his research, writing and publishing of The Art of Walt Disney. The answer to many of my questions was greatly aided by the Robert Durant Feild papers housed at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

-

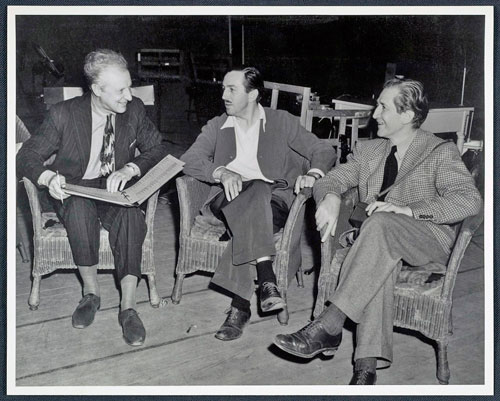

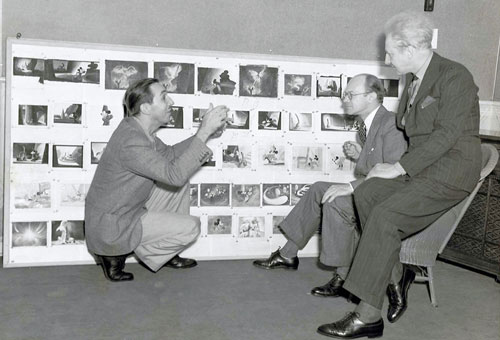

Leopold Stokowski, Walt Disney and Robert D. Feild in 1939 during the making of FANTASIA.

The Art of Walt Disney, republished by Collins in Britain in 1945 and 1947.

Following here is what I found out.

EARLY LIFE

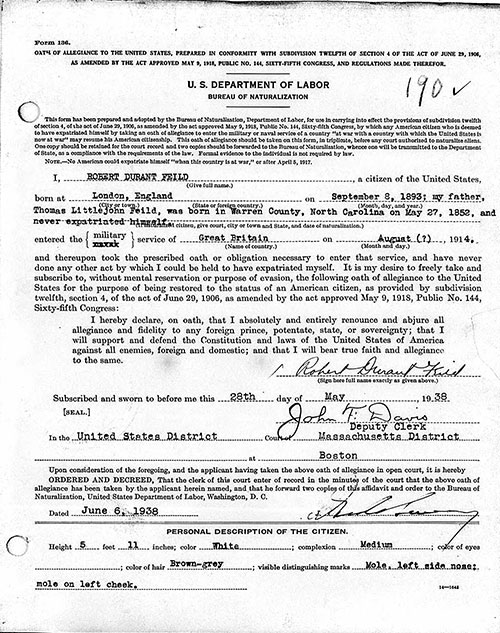

Robert (“Robin”) Durant Feild was born in London, England on September 8, 1893, and raised in affluent Kensington.1 His parents, Thomas Littlejohn Feild (1852 – 1937) and Meeta Armistead (Capehart) Feild (1862-1944), came from Raleigh, North Carolina, and, according to Robert D. Feild’s 1947 vita, “they never gave up their American citizenship.” (Robert D. Feild became a naturalized citizen of the USA on June 6, 1938.)2

His parents’ marriage took place at a lavish ceremony at Christ Episcopal Church, in Raleigh, in February 1891, described by the Daily State Chronicle newspaper as “one of the most brilliant occasions ever witnessed” with the “contracting parties coming from the highest social circle.”3 The 39-year old groom was “a promising young shipping merchant of London, a member of a large transportation company whose steamers ply between that point and Baltimore.”4 His 29-year old bride, the daughter of a prominent citizen of Vance county, was “a woman well equipped by her culture to adorn a model English home.” After an elaborate reception, the newlyweds left on a 1 a.m. train. “After visiting several points in this country, they will sail for Europe in April,” reported the State Chronical.5

Little more than a year later, Robert’s brother, Armistead Littlejohn Feild, was born in London on February 21, 1892.6 The next year in September, Robert was born. By 1901, the affluent Feild family, including a governess, a maid, and a cook, were living in a posh three-story townhouse at 13 Palace Garden Terrace, in Kensington. 7

Robert’s early education was at St. Vincent’s Preparatory School (1903-07), and the prestigious Harrow School (1907-10), founded in 1572 under a Royal Charter granted by Queen Elizabeth I. At age 17, he began to work in a London stockbroker’s office for two years, before deciding to “become an artist.” 8

ART TRAINING, WORLD WAR I AND INDIA

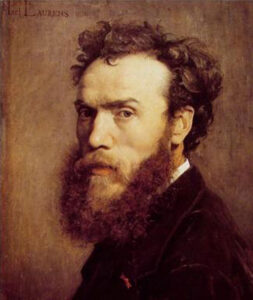

From 1913 until the outbreak of the First World War, in June 1914, Robert Feild studied at the Académie Julien in Paris. One of his teachers, John Paul Laurens (1838-1921), was a highly respected “classical realist” painter in the grand French Academic style. His staging, lighting of luminous color compositions of historical/religious subject matter hold a dramatic, cinematic quality. Laurens was strongly anti-clerical in his paintings, often passing “on a message of opposition to monarchical and the churches mistreatment and oppression.”9

The painter’s artistic and political messaging may have influenced young Feild. It presages his secular humanist beliefs, and his future clashes with academic defenders of fine art who derided his opinions about the merging of art and science. “We in the West seem to have lost our belief that the joy of being alive is an essential factor in spiritual growth,” Feild commented years later in The Art of Walt Disney. “With the rising power of the Church and its patronage of the arts, which amounted to a virtual monopoly, all outlets of humorous expression seem to have been discouraged.”10

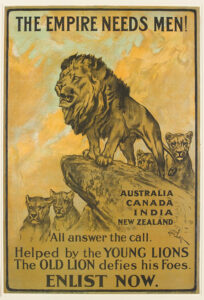

In August 1914, less than a month after war was declared, 21-year-old Feild enlisted for military training in the Honorable Artillery Company, the oldest regiment in the British Army, which dated back to 1537 and the reign of Henry VIII. During World War I, Feild later became a commissioned lieutenant in the Queen’s Own (Royal West Kent Regiment), serving four years overseas, until December 1919 on the North-West Frontier of India. 11

His India experience “was to profoundly impact him for the rest of his life,” notes Dr. Susan House Wade, a design historian specializing in visual culture exchanges between East and West during the first half of the twentieth century. Feild “wholeheartedly” embraced Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of democratic socialism and non-violence and “became involved with Indian art and philosophy. Indeed, India became one of his primary passions, with its art forming an integral part of his life.”12

WORKING IN THE USA

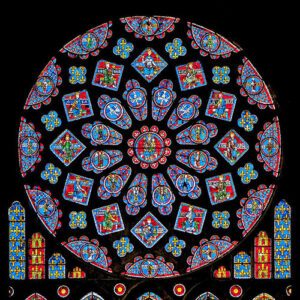

After the war, Feild continued to study painting in Paris and Rome “before deciding to ‘try my luck’ in the United States.” He spent two years “turning my hand to odd jobs throughout the country,” including an apprenticeship in Boston to a stained-glass maker. “Light in one of Mr. Feild’s living room windows,” wrote Gwen Kinkead years later in The Harvard Crimson, “shines through a round stainglass [sic] of St. Francis, a gift of his employer [when he was an apprentice]. His sensitivity to light and color were further enhanced at the Disney studios in the late 1930s.”

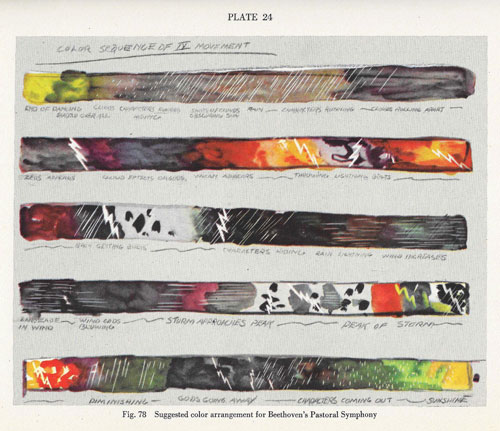

The luminous full rainbow of three-color Technicolor in Disney films, which began in 1932 with a Silly Symphony (FLOWERS AND TREES), was equally enchanting to Jean Charlot, painter, muralist, and author of Art From The Mayans to Disney. “[Disney artists] have now reached a stage,” Charlot wrote in 1939, “where local color has been added to the black outline, where they resemble Gothic windows whose opaque leading partitions light into color . . . We have already seen the seven dwarfs, emerging from their cave into the sunset, shed their flat Gothic livery for the contrasting light and shade of the High Renaissance!”13

On February 5, 1924, in New York City, Robert at age 31, wed 27-year-old Helen B. Stickney (1897-1992), an American born in Cincinnati, Ohio. Now married, but with his “luck” as an artist not panning out, Feild urgently sought a new career. Helen, he wrote, “has been active in social work for many years.” Surely, it was she who sparked his attendance, brief though it was, at the Chicago University School of Social Service Administration (SSA) as a “Special Student.”14

During his time at the SSA, he worked under Paul H. Douglas (1892-1976), a passionate crusader for civil rights in the U.S. Senate, described by Martin Luther King, Jr. as “the greatest of all the Senators.” Other teachers of note included T.V. Smith (1890-1964), professor of philosophy, who also became a U.S. senator and author of numerous bills aimed at reforming the legislative process; and Harry A. Millis (1873-1948), prominent economist and author of landmark writings on labor relations.

Feild’s Social Service Administration teachers and his war experiences greatly shaped his progressive world view regarding social consciousness. His love of Far Eastern art and the Gandhian philosophies that he and his wife shared were also important art influences. “As a result of my experience at Chicago,” Feild wrote, he “decided to ‘become a teacher.’”15 Teaching in the classroom and writing would become his life work, with an avocation in painting.

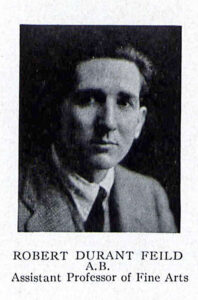

TEACHING AT HARVARD

Harvard University’s Department of History of Art began in 1874 as one of twelve divisions. In June 1927, the new Fogg Museum of Art opened to accommodate the growth of Harvard’s art collections. That same year, Robert D. Feild was offered a position of Instructor in Harvard’s Fine Arts Department. His eclectic credentials — studying art and painting in Paris and Rome, his practical work in a Boston stained-glass studio, his experiences at Chicago University School of Social Services Administration, and his military wartime service – so impressed the hiring committee that he simultaneously entered Harvard College as both a teacher and a freshman at age 34.

Feild graduated in 1930, magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, and a member of the exclusive Signet Society, which celebrates the arts of music, visual arts, and theatre. Signet members are chosen “with regard to their intellectual, literary and artistic ability and achievements.” The club’s emblem holds a beehive and a Greek legend: “Create art and live it.” Another club motto is attributed to Virgil: “So do you bees make honey, not for yourselves.” 16

At Harvard, Dr. Wade notes, Feild taught design theory and practice, and the history of British painting, specializing in the art of J.M.W. Turner. During this time, he also developed a lifelong friendship with Oriental Art lecturer Langdon Warner (1881-1955), among other East Asian art colleagues. “Up to our contemporary period,” Field wrote in The Art of Walt Disney, “Japanese Kamakura scroll-painting is perhaps the greatest example of dramatic and humorous story-telling ever attained.”17

His academic friendships also “formed Feild’s core views on the ‘Unknown Craftsman’ . . . with reference to those involved in anonymous craft production.”18 He would later find the Disney studio a modern example of a Renaissance workshop, made up of unknown artist/ craftsmen and women, where many hands contribute to a single artistic goal.

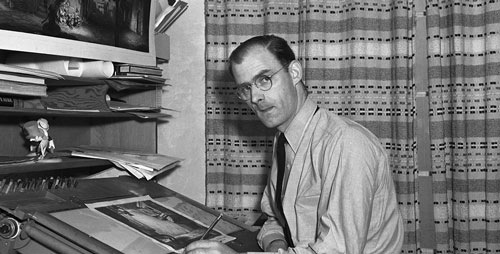

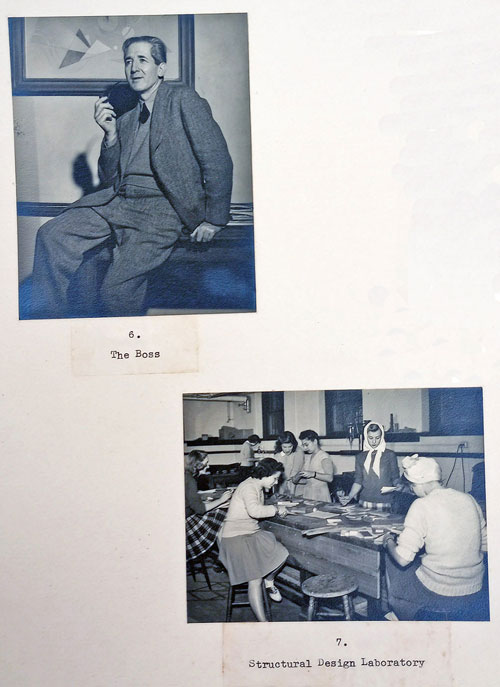

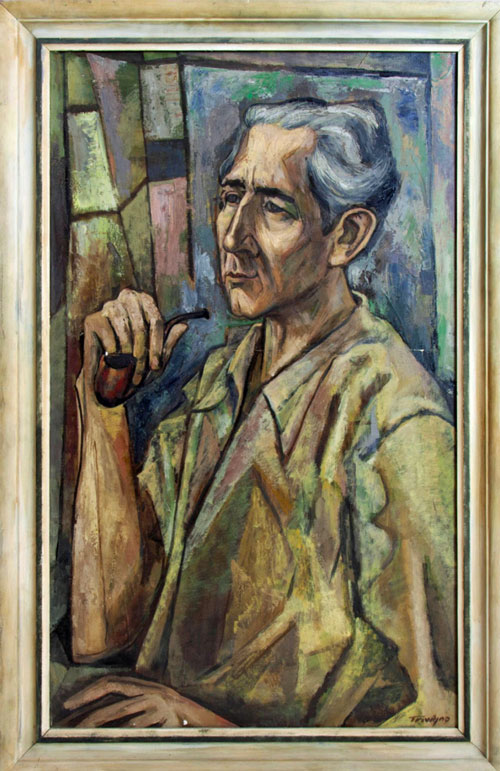

Robin Feild was a charming, witty, and gentle teacher, with an outspoken “fighting spirit” regarding art and his socialist politics. He continued teaching at Harvard until 1939, the last six years as an Assistant Professor. He was well-liked by his students. The New York Times described him as “of the ‘studio type,’ sitting at ease with them at table and smoking over their common interests.” The Harvard Crimson noted that “most aspects of ‘the adventure of living’ absorb Mr. Feild, and he has no hesitation to speak a piece of his mind.”19

I had for many years become vitally interested in new materials and new techniques for the communication of contemporary ideas,” he later said. “20 Indeed, Feild could be passionate and straight-forward in challenging academic colleagues and fine art critics resistant to breaking down barriers between art and science. “Many continued to hold the belief that the machine is the enemy of art,” he wrote in 1942, “and that a picture not all done by hand is beyond the pale of artistic judgement. So it is that the work of Walt Disney, whose art has been developing steadily over a period of fifteen years, has taken us by surprise.21

Frequently, when Feild voiced his admiration of filmmaking as a new, vital, scientific art form, he championed the animated films of Walt Disney (1901-1966) as a prime example. In less than a decade (from 1928-1937), Disney’s Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony cartoon shorts rapidly progressed technically and artistically using innovative camera and film optics in tandem with advances in sound, color, design, and expressive cinematic narratives.

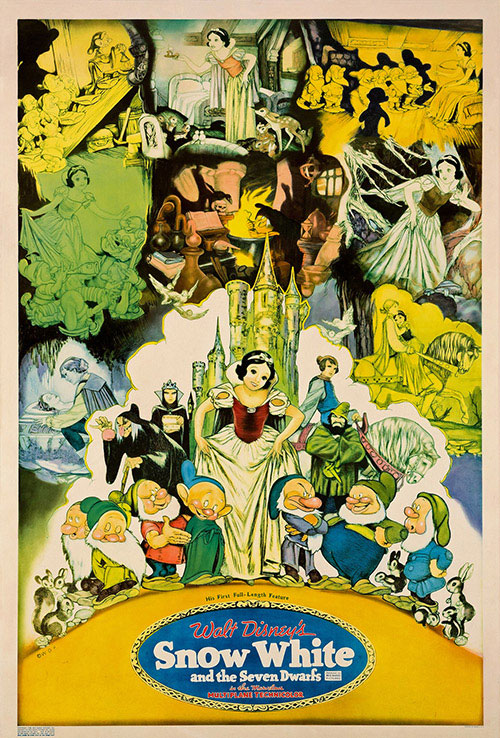

The culmination came in 1937 with the world-wide success of Disney’s first feature-length cartoon, SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS, which revolutionized the art and commerce of animation. Walt and his moving-image artists and technicians were at their highest creative peak in, what Feild described as, “perhaps the only universal art form in history . . . what I like to call 20th century folk art.”22

Feild’s Harvard students were enthralled with their opinionated art teacher. The Harvard Crimson, the undergraduate student-run newspaper, described him as the Fine Arts Department’s “most popular and successful professor.” Despite Feild’s popularity with his students, a storm was brewing among his academic colleagues.

In the late 1930s, Harvard’s art faculty was engaged in a raging debate over so-called high vs low art — a resistance to popular or commercial culture encroaching upon the temples of traditional fine art. Use of technology to create photography and movies was looked upon by some with suspicion and disdain.

The debate continues today. Artist David Hockney’s iPad pixel paintings, for example, and his theory that Old Master painters may have used optical aids, such as mirrors, lenses, and the camera obscura are controversial. Hockney’s embrace of digital creativity “belongs to age-old suspicions about art’s relationship to machine technology,” observes Karen Fang, historian/author and University of Houston professor. It is also “a distinctly twenty-first century anxiety about screen culture.”

When Feild’s situation climaxed in his dismissal from Harvard, the New York Times noted that “in the judgement of a majority of the fine arts faculty, Professor Feild put too much emphasis on modernistic styles.”23

MEETING WALT DISNEY

Before that happened, fuel was added to the fire when Harvard University president James Bryant Conant invited Walt Disney to Harvard to receive an honorary Master of Arts degree on June 23, 1938. It was said that Professor Feild “was responsible” for suggesting that the prestigious award be given to Disney, who accepted the invitation with enthusiasm. 24

So great was Walt Disney’s fame and popularity that on June 22, the day before arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts to receive Harvard’s award, he stopped by New Haven, Connecticut to pick up another honorary M.A., this one from Yale University. “Who was this man Disney, anyway?” Feild later wrote with wry wit about academia’s sudden regard for Disney:

He must be recognized as a social benefactor; and so, learned institutions competed with one another to show how much respect they had for a man with such a charming sense of humor. But [Walt] . . . knew all about it. He knew that immediately after Commencement the learned institutions would begin again exactly where they left off. They would return to the study of Art with a greater determination than ever to escape into the past.25

At Cambridge, Professor Feild met Mr. Disney, where undoubtedly the former enthused about the latter’s filmmaking achievements in developing a new art form. They may also have conversed about the possibility of Feild visiting Los Angeles for a close look at the Disney animation processes, with an eye toward organizing an art exhibition. Or, perhaps, writing a scholarly book that would inform an avid public curious about how Disney films are made. A book to stimulate art students and contribute to “standards by which to judge the art of today,” as Feild later wrote in the Foreword to the tome that became The Art of Walt Disney. “Because his art does not fall into any one of those traditional categories which we have learned to accept as particularly ‘fine’ . . . it has been presumed that it is outside the range of legitimate art criticism.”26

Walt Disney was receptive to producing an informational book on animation art and technique. In fact, as a teenager beginning his career, he first learned how to animate from E. G. Lutz’s 1920 book Animated Cartoons – How They Are Made, Their Origin and Development (Charles Scribner’s Sons), which he frequently borrowed from Kansas City’s Public Library. 27

RESEARCH IN HOLLYWOOD

The Harvard arts professor apparently impressed the Hollywood film producer. Soon after Harvard’s ceremony, Feild spent six weeks of his 1938 summer exploring the Walt Disney studio in Hollywood. During his stay (and a longer one the next year), Field was given free rein to explore the secrets of how the Disney sausage is made.

“No doors were closed to me,” he wrote, “no obstacles put in my way, lest I probe too deeply into the ‘mysteries of the craft’; nor was I ever made to feel that I was the nuisance I often knew myself to be.”28

Walt did request that Feild present a lecture about the animated cartoon as “the art of the future.” On Tuesday evening August 9, 1938, a large gathering of Disney artists and artisans “jammed the Hollywood Las Palmas Theatre” to hear the professor’s talk. “When I was asked by the authorities, if I would talk to you,” Feild joked in his opening remarks, “I felt, more or less, as if I was receiving orders from headquarters.”

Most of Feild’s lecture dealt with a question he often posed to his students: What is the meaning of the word Art? Ruminating at length in broad strokes, punctuated with humor, he sketched a history of Art, decrying a contemporary “unintelligent reverence for the past . . . and the stupid aversion to the machine.” In film animation, “the machine” is the necessary integration of optical equipment and scientific electronics. Cameras, lighting, film emulsion, image projectors merge with traditional drawing/painting skills and tools to produce moving imagery, eliciting emotional responses from viewers.

Toward the end of his talk, Feild suggested recovering the “lost” and “correct” meaning and use of the word Art, as understood by Aristotle in Ancient Greece, Meister Eckhardt and other medieval scholars in the 12th century, “taken for granted throughout the whole of the Renaissance.” He included art from his beloved India because “it is the way the word has been understood and acted upon through all history.”

“The ‘Art’ in anything,” Feild finally revealed, “is the degree in which it is well done.”

It applies to the doing of anything; writing a symphony, sailing a boat, making love. It also applies to running a business, punching a man on the nose or constructing a machine gun . . . We have always associated it with things pleasant, rather than unpleasant. But here again we have been careless in our thinking. We have avoided the main issue. It is the right use of “Art” which goes into the building of any worthwhile culture.

The most important problem, he explained, is “the worthwhile-ness of doing anything . . . to find the right use for Art.”

As dark political clouds gathered in Europe, where within a month Hitler would invade Poland initiating World War II, Feild’s lecture referenced Gandhian values of truth, non-violence, harmony and simplicity:

I suppose we are all agreed that one of man’s functions as a social animal is to work for the good of the whole. In a sane world, then, rather than making a machine gun well, rather than to exploit mankind and torture him to death, Art should be used in the endeavor to preserve life and beyond that, to make the world a better place to live in. To strive to make people happy, then, is no unworthy artistic aspiration.

“You are rediscovering the real art of representation,” Feild assured his Disney audience, “and bringing it into line with all the accumulated resources of man’s discoveries and inventions up to date.”

You have broken down utterly all possible conflict between man and the machine. And you are putting science to use to aid in the production of something essentially for a man’s good in terms of what is Beautiful.

In conclusion, Feild spoke to the Disney staffers about “the privilege to consider himself or herself an artist in their own right.” Showing off what he’d learned about animation production processes in his brief time at the studio, he noted:

Whether you are in what is referred to as the Creative or the Process section of the plant — from what may be considered routine work on the cells [celluloid acetate pages on which the paper cartoon characters are inked and painted], to the Unit Directors; from the mechanics to the head engineers. For if what I have said about “Art” means anything to you, you will realize that only to the degree that you do each part well can the whole be done well. And actually, there is just as much “Art” in painting a cell well as in the work of the animator. That I know is a shock to some of you, but such is the case. 29

That fall, Feild returned to Cambridge to resume teaching his classes, confident in the knowledge he gained firsthand about Disney’s art. He planned a series of lectures on the subject for Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum. And a book proposal.

At the same time, he was contacted by Alfred Barr, first director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Barr wished to discuss Feild’s work at the Fogg “which interests me so much and about which I heard a great deal . . . My secretary tells me that you have some Disney material. Have you talked to the [MoMA] Film Library about its use?” 30

Where did Barr’s keen interest in Feild and his lectures come from? The answer arrived the next day in a letter from Barr’s assistant, Allen Porter: “Mr. Edward Warburg has told us of your summer at the Disney Studios and of the material you collected there which you hope to incorporate into a lecture.”31

Edward M.M. Warburg (1908-1992), a philanthropist, was one of the founders of MoMA and a co-founder of the American Ballet company with George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein, Warburg’s Harvard classmate. Warburg graduated from Harvard Class of 1930, the same year as Feild. As a student in 1928, Warburg founded the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, which “gave the public its first look at one startling art form after another.”

It was a precedent for what MoMA became. Warburg explained, it was “our form of militancy” against the “all reactionary” Fogg Art Museum. Feild’s interest in modern art forms was nourished by the educational art exhibitions held by his classmates Walburg and Kirstein. In rented rooms at Cambridge, they exhibited original artworks by Alexander Calder, Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Buckminster Fuller, among others.

Warburg, now intrigued by alumnus Feild’s progressive film theories and the Disney lectures he was planning for Harvard’s staid Fogg , recommended that Barr also consider them for MoMA.32 John Abbott, Director of MoMA’s newly formed Film Library and Iris Barry, its first curator, soon began a correspondence and meetings in New York with Feild. A letter from Abbott, dated January 26, 1939, discussed “the question of the Animated Cartoon Exhibit, coupled with the possibility of three lectures on this subject by yourself.” 33

Professor Feild was not only popular among Harvard students, but becoming a figure of increasing attention at a major art institution. The new year was moving along well for Professor Feild. Until it wasn’t.

DISMISSAL AT HARVARD

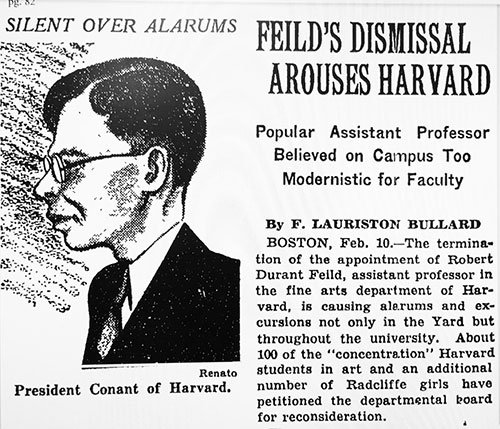

In early February 1939, Harvard pulled the rug from beneath R. D. Feild by not renewing his teaching contract. The term of the popular art teacher of distinction, with twelve years of experience at Harvard, would cease at the end of the academic year in September.

Reaction was swift and intense. The New York Times reported the termination “is causing alarums and excursions not only in the [Harvard] Yard but throughout the university. About 100 of the ‘concentration’ Harvard students in art and an additional number of Radcliffe girls have petitioned the departmental board for reconsideration.”34

The reason for Feild’s dismissal was never officially revealed. However, The Nation magazine repeated The Harvard Crimson’s assertion that the university’s art department had been “rankling” over Walt Disney’s honorary award since June. The “incident was the immediate reason, though Dr. Feild’s general approach to art, which made his classes so popular that not all applicants could be accommodated, was a more fundamental reason.”

A Harvard Crimson editorial claimed the problem lay in the department’s stressing a chronological, historical, factual approach to the Fine Arts “filled with names and dates.” The students felt it failed to offer them methods to judge art for themselves, “the universal essentials which lie behind all art.” Attainment of such a goal meant teaching the R.D. Feild way:

. . . greater stress on practical art and design; and more than this, a close integration of practical work and history. It means the coordination of art with other branches of knowledge. It means finally the demonstration of the connection between the Fine Arts and the present-day world. The arts would consequently cease to be beautiful expressions from a past period of history and would become something of living significance. 35

The Cambridge Union of University Teachers expressed “profound regret” over the failure of Harvard University to renew Feild’s teaching appointment. “Seeing in the incident an illustration of the ‘need for reform in the system of appointment and tenure at Harvard,’ the teacher’s union questioned whether ‘efforts for a fresh point of view’ were being made in the fine arts department and asked further, whether Harvard could afford at this time to lose ‘another undergraduate teacher of proved distinction.’” 36

A general investigation of the Harvard tenure and appointment system had, in fact, been under way for months. Feild may have been involved in attempts to form a non-tenured teacher’s union at Harvard, “which cost Feild . . . and other faculty members their jobs.” The Cambridge Union was demanding an answer to “how long a department could utilize a teacher without ‘incurring responsibility for his career.’”37

Dean George H. Chase, a member of the “high-ranking” Harvard art department committee that recommended against Feild’s reappointment, downplayed the angry campus reaction: “It is just one of those cases where a man is not recommend for reappointment.” Harvard president Conant was silent on the matter.38

Walt Disney, however, was not. He responded to a query from The Christian Science Monitor with a telegram: “Robert Feild is held in high esteem by our staff of over 300 practical artists. I don’t know of a better recommendation and can only say Harvard’s loss will be someone’s gain.” 39

At the time of his firing, Feild, was “ill at his home from influenza” and made no comment. However, one week later (February 16) he recovered sufficiently to offer the first of four lectures on “the art of Walt Disney” and the animated cartoon at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum. It may have been cold comfort to Feild that, as The Boston Globe reported, the talk “drew such a large crowd last night that 500 were turned away. The capacity of the lecture hall is 400.” 40

The Nation magazine, noting that students and teachers at Harvard were organizing, commented with amusement: “We look forward to a good fight. The spectacle of Harvard defending its dignity against a Mouse should be almost as funny as an animated cartoon; it should inspire Mr. Disney to send Donald Duck and all his other extra-curricular animals to Cambridge.”41

A DISNEY BOOK PROPOSAL

Academia being academia, nothing came of the tempest. Feild was not rehired. But during the short-lived fracas, he proposed a book on Disney’s art and creative processes to the Boston publishing company Houghton Mifflin. In mid-March, Houghton editor Richard J. Eaton wrote, “My dear Mr. Feild, I am curious to know whether you have yet found time to write to Walt Disney” for the necessary permissions to proceed with the project.42

Field indeed planned to meet with Disney in New York in May after Walt oversaw music recordings conducted by Leopold Stokowski in Philadelphia for the soundtrack of the “concert feature” in production, later titled FANTASIA (1940). But Disney was taken ill in New York and returned to California. He finally responded to “Robin” Feild on May 17, expressing he was “very sorry to hear what happened at Harvard, but, after all, it may be for the best.”

He then got down to business regarding Feild’s book proposal:

I have given a lot of thought to your suggestion that you write a book on the animation of cartoons. I want to be frank and say that I think anything of this nature, which has our approval, should be done in close cooperation with the studio, because there are many angles we have learned from the practical side that should be incorporated into a book of this sort if it is going to serve its purpose of stimulating interest in the art student and also be a contribution to the cartoon industry. We definitely feel that you are qualified to write this book and we want you to know that you have our complete confidence and cooperation, not only in the writing of this material but also in the marketing of it. Please let me know how your plans develop, and with all good wishes, I am

Sincerely, Walt Disney 43

On May 26, Feild assured Eaton of Disney’s full cooperation, and revealed plans to travel with his wife, Helen, to Los Angeles for an extended research period at the Disney Studio. Delighted, Eaton responded:

Will it be possible for you to prepare a tentative plan or prospectus of your book before you leave? . . . I am very glad to hear that you are still willing to give Houghton, Mifflin Company the first chance at your book because of my being first on the ground, as it were. Judging from your course of lectures early this year, I am inclined to believe with you that you will not encounter any difficulty finding a publisher in the event Houghton Mifflin Company prove to have cold feet. 44

However, the book eventually was published in 1942 by The Macmillan Company. Whitman Publishing, a subsidiary of Western Publishing Company and Disney’s book publisher since 1933, arranged for Feild’s book to be published by Macmillan “under our authorization, the complete manuscript and arrangement of the material, as approved by Walt Disney Productions.”45

“The material upon which this book is based,” Feild explained in his Author’s Note in The Art of Walt Disney, “I collected in Hollywood between June 1939 and May 1940.”46 Feild financed some of his research-gathering trip with an extra year’s salary given to him by Harvard “as a solatium,” a compensation for the inconvenience of his recent unemployment.47 The book contract wasn’t worked out until late March 1941, when Feild’s manuscript was nearly finished. The publisher paid the author an advance against royalties of $1,750.00, comparable in today’s dollars to approximately $38,000. (According to the 1940 U.S. Census, the average annual salary was $1,368.)

Feild would complain later that the actual writing and editing of the book was “a God-awful series of vicissitudes” in “the publishing racket,” which is “like any other exploitation-for-profit-concern.” By contrast, he and Helen always remembered their nearly year-long Hollywood stay, with Robin freely touring the Disney studio gathering information and learning about the art of animation, as “one of the happiest of our lives. I got something out of the Disney Studios,” he wrote to a friend in 1941, “which in some strange way has meant more to me than I ever remember having experienced before.”48

RETURN TO HOLLYWOOD

Before the Feild’s arrival in Hollywood in June 1939, and before Robin reported to the Disney studio in July, he contacted artists he had befriended there the previous year.

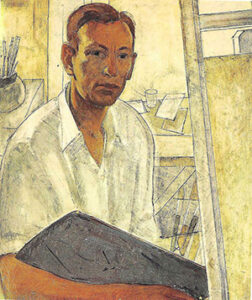

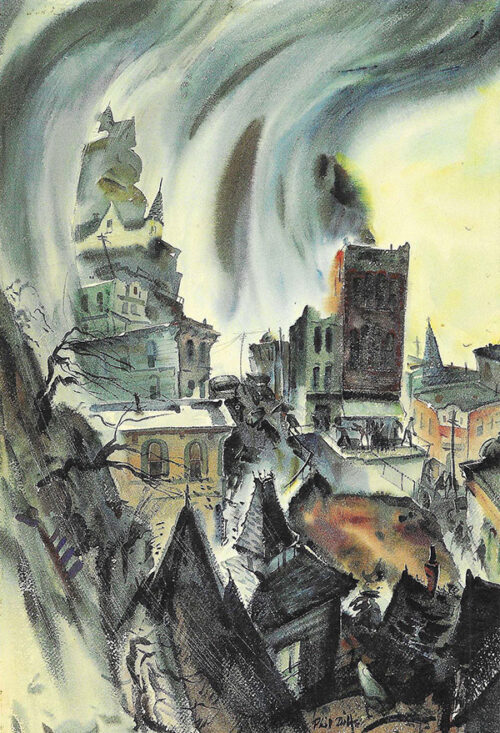

One was Phil Dike, a conceptual sketch artist, color coordinator/advisor for SNOW WHITE and FANTASIA. A founder of the California school of watercolor, Dike taught drawing and composition at the Disney studio from 1935-45. He shared with Feild a mutual interest in art history and teaching, and became one of several Disney staffers who gave Feild “unsparingly of their time in all emergencies.”

One was Phil Dike, a conceptual sketch artist, color coordinator/advisor for SNOW WHITE and FANTASIA. A founder of the California school of watercolor, Dike taught drawing and composition at the Disney studio from 1935-45. He shared with Feild a mutual interest in art history and teaching, and became one of several Disney staffers who gave Feild “unsparingly of their time in all emergencies.”

To the professor’s inquiry about locating a Los Angeles apartment, Dike responded immediately with a June 5 letter of welcoming warmth, good humor and encouragement:

Dear Robin,

I have been hearing of your escapades of the past few months and can well imagine that Cambridge has held an unusually exciting spring. Your assignment with us sounds like a very interesting opportunity, not only for the Studio, but for this thing called “animation,” or “the animated picture.” I am sure you will get a big kick out of digging into the many possibilities that come to mind when one thinks of the inner workings of such a place as this. It is fortunate that you were here last summer and it should not be as if you were stepping into a place where angels fear to tread. I shall be looking forward to seeing you in July, and if I hear of a place in the vicinity of which you spoke, I shall make a note of it so that you may have some choice when you arrive. 49

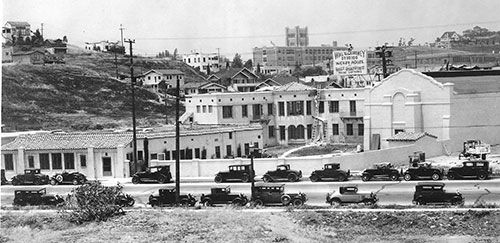

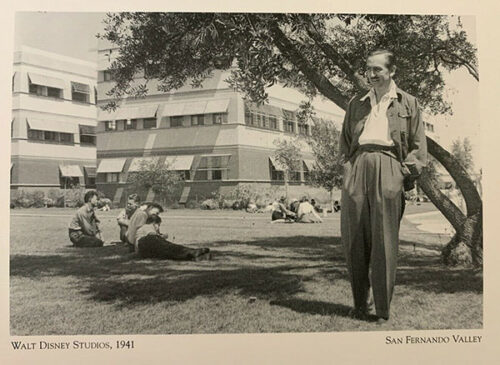

The Feilds rented a cozy apartment at 1901 Commonwealth Avenue at Franklin Avenue. It was conveniently located about a mile from 2719 Hyperion Avenue in Los Angeles’ Silver Lake district, an address housing, since January 1926, the Walt Disney Studio.50 The now-legendary Hyperion studio was the birthplace of Mickey Mouse, a fact no one entering the small greenery-lined courtyard could doubt. For above Spanish-style stucco buildings with balconies, a giant neon sign of the famed mouse smiled and waved, as if in welcome. The returning ex-Harvard professor did indeed feel welcomed, and ready to immerse himself fully in a Hollywood dream factory like no other, during a peak creative year.

That summer of 1939, Walt Disney’s bustling film studio was enjoying worldwide acclaim as the home of Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony shorts, and the breakthrough animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Released in 1937, after three years of creative innovation and sheer toil, Snow White immediately achieved worldwide critical and popular success, becoming America’s highest grossing film. Product merchandising of the many beloved Disney film characters in toys, books, clothing, alongside lucrative European film distribution deals, added additional profitability to the studio’s coffers.

Emboldened and flush with money, Walt Disney ambitiously planned to produce two animated features per year, as well as a full plate of shorts. But the way forward was not easy. “The two years between Snow White and Pinocchio,” he wrote, “were years of confusion, swift expansion, reorganization,” During 1938-40, eight hundred people were added to the payroll, bringing the total of employees to approximately 1,400.51

The creative challenges of upcoming productions (Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi) and those in early development (Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland and Cinderella) were formidable and expensive. Physically, the Hyperion Avenue studio was bursting with new infusions of artists, technicians, and equipment. For extra space, additional neighborhood buildings, apartment houses and bungalows were rented, purchased or leased. Story artists for Bambi (released in 1942) were housed across town on Seward Street. “We needed a new studio,” Walt decided, “and in a hurry.”

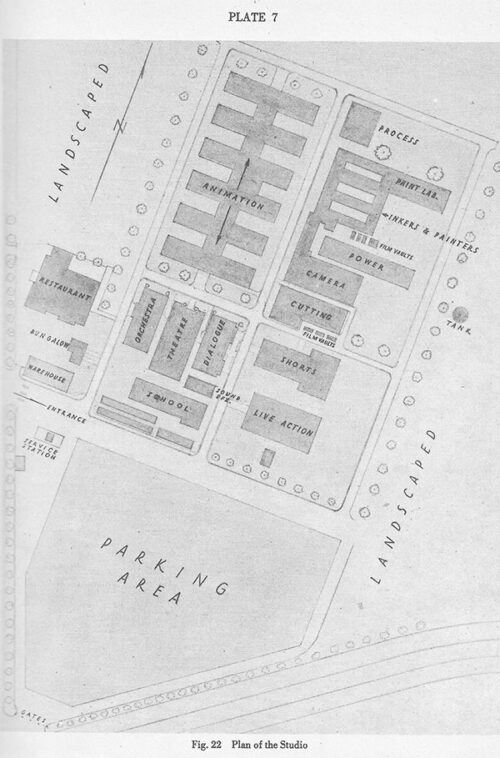

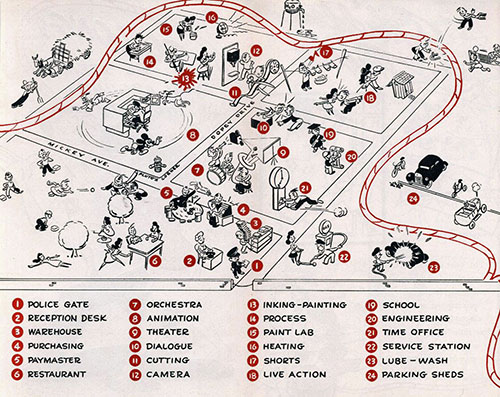

Planning began in May 1938 for construction of an elaborate $3 million, air-conditioned facility on 51 acres in Burbank, eight miles away in the San Fernando Valley. The first wave of Hyperion studio employees to abandon the old facility began arriving in the new but unfinished Burbank studio in late August 1939.

For nearly a year, from summer 1939 to May 1940, first at Disney’s Hyperion studio and then at the new Burbank studio, Robert D. Feild was a keen eyewitness, to a remarkable, exciting, but brief, creative period in animation history. His intelligent on-site observations in elegant prose would be published in 1942 in a landmark book, the first its kind to reveal and explain in depth the art and craft of animation at the Walt Disney Studio.

RESEARCH AT DISNEY, SUMMER 1939 – MAY 1940

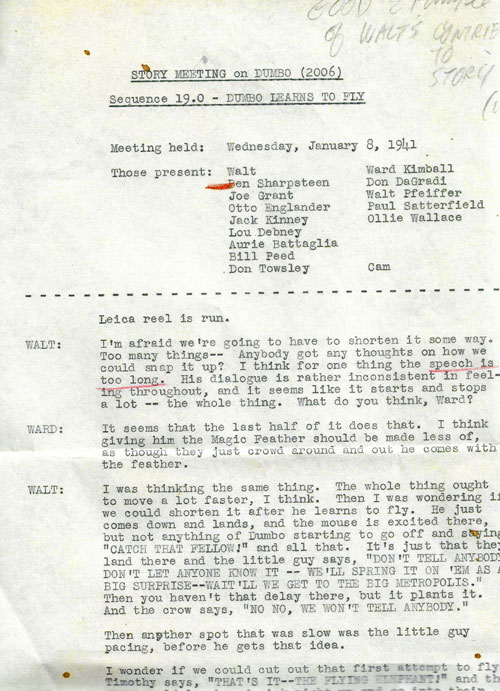

Feild’s methodical research at the Disney studio began by visiting every area of production: administrative, creative, and technical. Early on, he was impressed and delighted by the “Story Conference Technique,” perhaps because it was close to a writer’s task. But here it is a group effort, in which crews of story artists and writers write and draw sequential pictures. A lapidary method in which scenes and sequences of a film are developed, discussed, made fun of, and defended narratives (often passionately). A stenographer recorded their spontaneous arguments for later reference (profanity removed), and the inspirations sparked hundreds of hand-drawn storyboards.

At first, Feild was taken aback by the participants’ seriousness of purpose toward even the funniest narratives:

At first, Feild was taken aback by the participants’ seriousness of purpose toward even the funniest narratives:

I would sit back and chuckle at the adventures of Mickey and the gang . . .when I would happen to look up and see perhaps ten or twelve strong, silent men – their jaws well set, looking as if they were attending a war conference . . . I would be on the verge of exploding with uncontrolled laughter when suddenly, whoever was in charge, would positively thunder out, “My God! [Donald Duck] would not act that way!” And with an expression of withering scorn, he would turn upon the poor wretched storyteller . . . I suppose only an outsider can fully appreciate the mysteries of the gag session. They are sort of unnerving if you are not accustomed to them.52

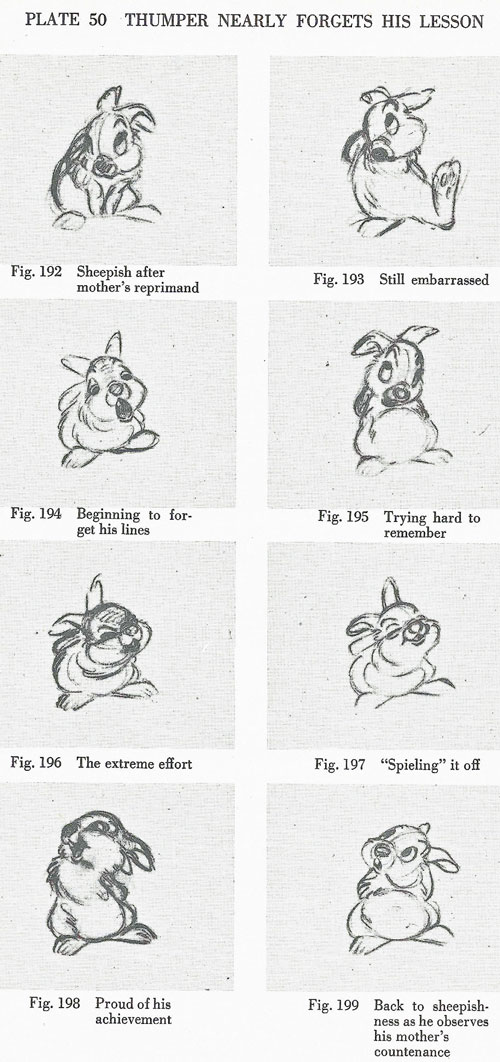

Feild’s book offers several glimpses inside Disney story conferences and how story continuities came to life in Snow White and her animal friends’ inventive house-cleaning sequence; Night on Bald Mountain’s Halloween imagery in Fantasia; earliest ideas for Dumbo; story continuity for a Donald Duck short, among others.

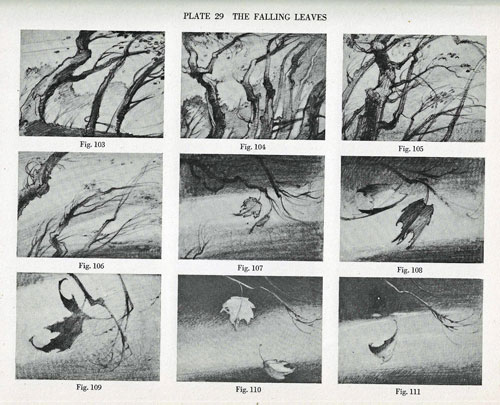

One poetic storyboard, adapted from Felix Salten’s original 1923 novel Bambi, A Life in the Woods, attracted the existentialist in Feild. It was a sequence of nine delicately-drawn pencil renderings of two autumn leaves. Wind-blown, about to detach from a tree branch, they have a sensitive and final conversation about life and death.

“Each moment of action,” Feild wrote, “had to be described in detail and every word of the dialogue phrased with the greatest artistic fidelity.” Unfortunately, the episode did not make it into the final film. But in Feild’s book, his inclusion and preservation of this lost moment reveals a ruthless creative process, wherein painstakingly developed ideas are often discarded.53

Feild’s 290-page The Art of Walt Disney briefly surveys pre-cinema art (cave drawings to comic strips), works that strived to bring vitality to still imagery in paintings, drawings, and sculptures. In another early chapter (“Flickers of Promise”), he admires silent-era cartoon films:

Many were crude to a degree, but at their best they not only fulfilled their purpose effectively but also attained a high standard of artistic accomplishment. In directness of appeal, in economy of means, consistent with the quality of humor they attempted to convey, they have never been surpassed. . . These early masters of the animated cartoon were laying the foundation for a new art form, a new way of appealing to the imagination; they were liberating us from our dependence upon the “still” picture as the ultimate form of drawing and painting. 54

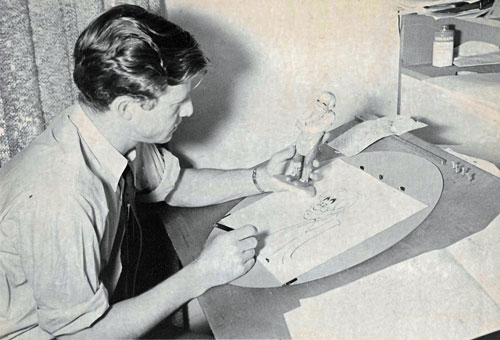

Feild questioned scenarists; storyboard and concept artists; designers of color, characters and background; layout composition planners, cel inkers and painters; camera operators and directors, supervising master animators and their assistants; and Walt Disney himself. He spoke with early animation veterans who improvised drawing and animation principles. Now working at Disney’s, their discoveries were developed, codified, and shared with younger colleagues.

Roaming the Disney production labyrinth during the making of the features and shorts, Feild visited supervising directors’ offices called “Music Rooms.” They were so named during the transition from silent to sound films when a composer at a piano helped the director determine a cartoon’s tempo and pacing.

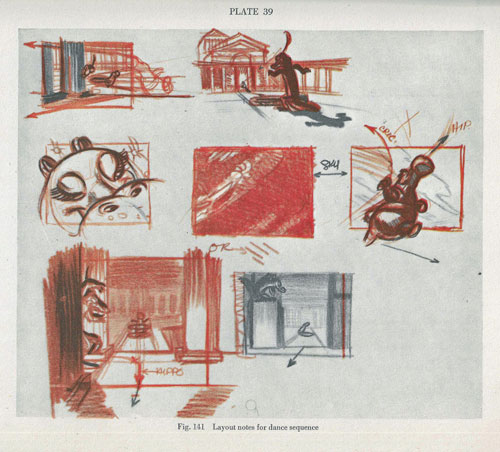

Feild developed a warm camaraderie with the Music Room denizens of Fantasia’s “Dance of the Hours” sequence, a wild satirical ballet of ostriches, elephants, and a hippo and alligator pas de deux.

In a letter written in early 1941 to T. (Thornton) Hee, co-director of the sequence, Feild recalled:

. . . the raucous tones that used to reverberate round your music room while I urged the gang to work — or did I used to whisper diffidently while you, Fergy (co-director Norman Ferguson), Ken (art director Kendall O’Connor) and Co. (Asst. Director Larry Lansburgh) scowled at my interference? Anyway, I had a swell time with you all, and if the book ever gets written, and any of it is passably good, you can all claim the credit.

Feild later reiterated to Disney publicist Janet Martin Lansburgh that the “happiest days I spent in the studio were in [her husband] Larry [Lansburgh]’s unit.”55

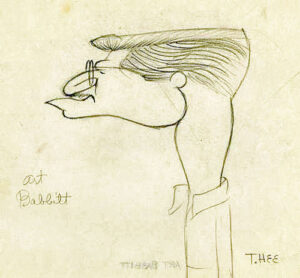

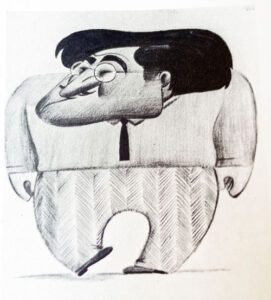

Feild visited numerous animator’s rooms as well, and was especially impressed with the artistry of master animators Art Babbitt and his close friend, Vladimir (Bill) Tytla. Babbitt and Feild, in fact, would maintain a friendship through the years, mostly exchanging letters.

In one, he told Babbitt, “You were greatly responsible for the positive goodness of the experience.”56 Informational explorations with top studio animators enabled Feild to elucidate about “a far higher standard of drawing” required at Disney for “an art of a new order.”

It was no longer sufficient merely to endow little cartoon characters with vitality. Animation began to demand an increased knowledge of organic structure, a new approach to the problems of design, and a more acute sense of timing. 57

Animators, Feild learned, must gain “a psychological insight” into cartoon characters, but “must also possess one more faculty hitherto never called into play in pictorial representation . . . [the ability] to feel exactly how the particular character would behave under all circumstances.” He concludes that to attain quality personality animation, what counts most is “the understanding the artists have derived from direct experience.”

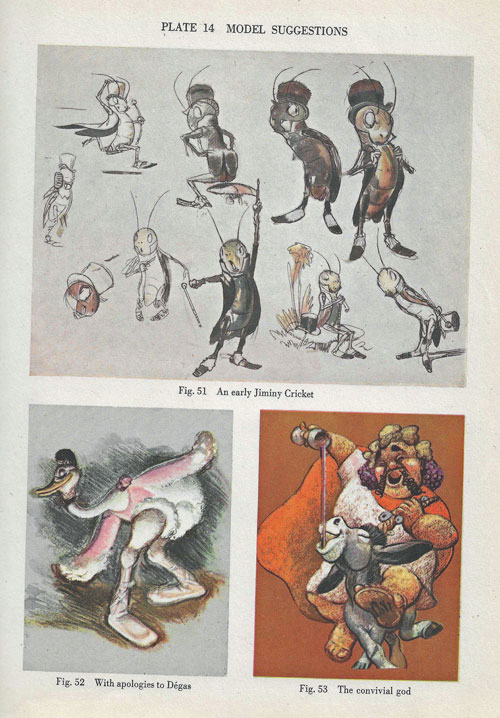

Many of the book’s illustrations favor the processes of animation revealed in rough conceptual drawings made of graphite, pastel, watercolor. Most of the showcased character drawings are off-model from their final film designs.

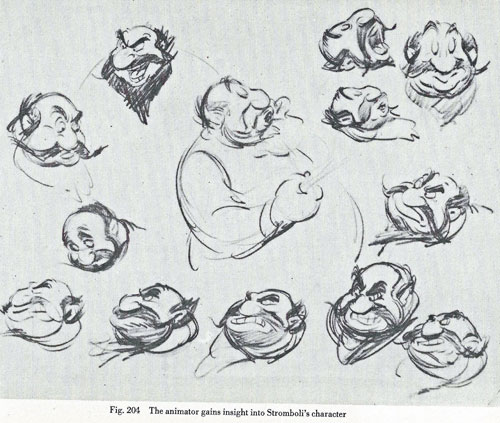

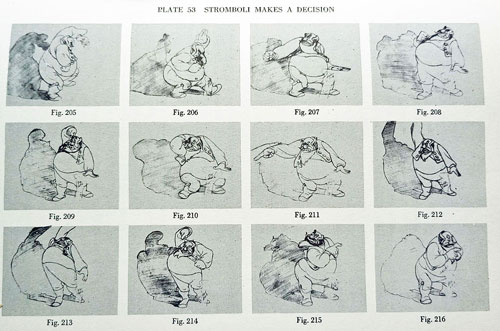

For example, a single page featuring thirteen energetic drawings, full of life, of the head and facial expressions of Stromboli, PINOCCHIO’s bombastic villain, are rendered in sketchy, bold, quickly-made lines by the supervising animator (Tytla). On the next page a Stromboli scene is composed of sequential animation drawings by a “clean-up artist.”

The assistants to each master animator had a difficult task: bring all loose, graphite lines on the sequential original drawings into tight, consistent shapes, with added details on new sheets of paper. Now on-model, the detailed clean-up drawings next went to “Inkers,” who traced the tightened lines onto transparent celluloid sheets (“cels”), filled in by “opaquers,” who painted colors on each cel.

Feild acknowledges that the drawings during this assembly line manage to “retain their monumental quality despite the rigors of the clean-up process.” But although “the vital spark [of the master’s roughs] has been retained,” Feild laments that often “they have been so cleaned-up and the lines reinforced with such a graven quality that they are almost offensively precise.”58

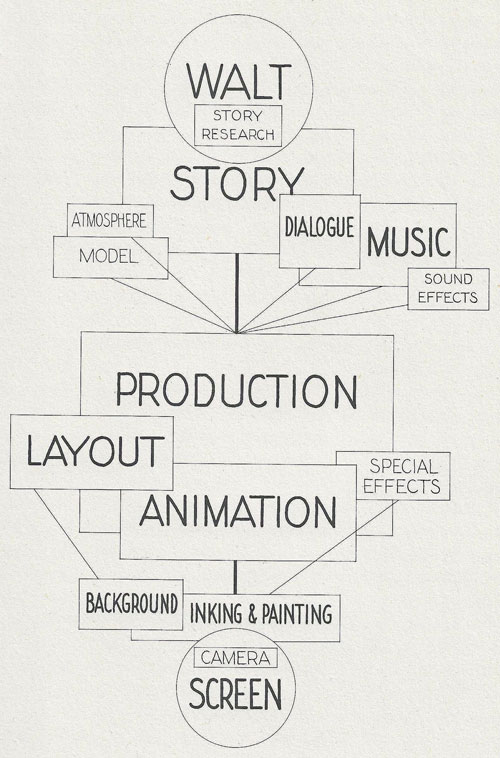

Feild’s nimble words dance alongside the book’s well-chosen 267 drawings and photographs, many in color. His text is also accompanied by a judicious selection of a tour of the new Burbank studio in photos, blueprints, and production diagrams.

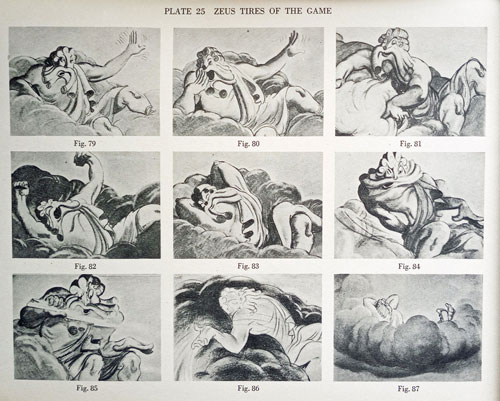

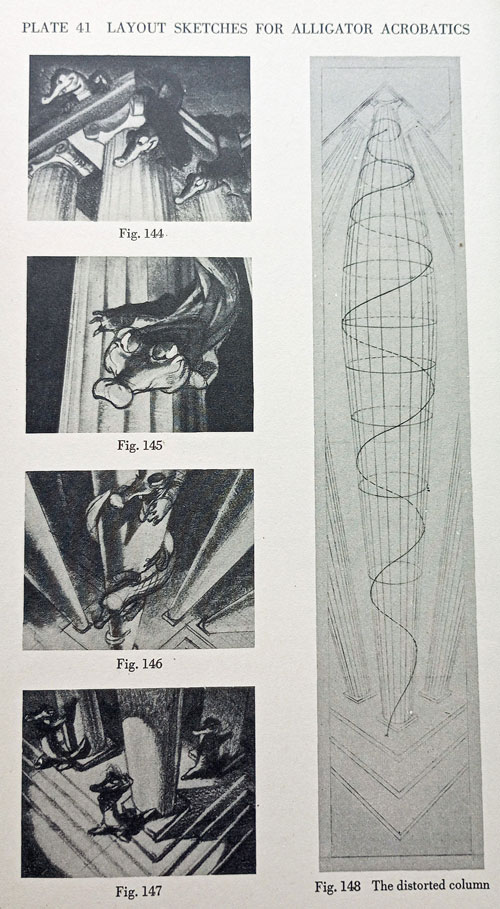

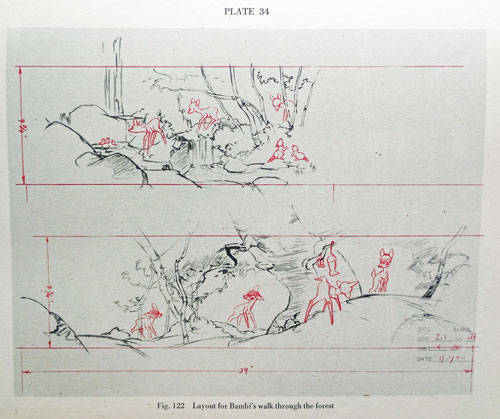

Feild illuminates as he entertains. Whether it’s Thumper reciting a homily, or a dancing hippo, or Zeus tossing lightning bolts, the reader is informed about the character’s visual development and, more important, the creative thinking behind the choices made. Storyboard continuity drawings of Pinocchio encountering a sly Fox and Cat; layout drawings of Bambi’s first forest walkabout; alligators slithering down a distorted Ionic column are eye-opening. The drawings are as much fun to see and learn about today as they were over 85 years ago. Technologies change through the years, but basic principles of visual communication are constant.

WRITING THE BOOK

In May 1940, Robert and Helen Feild returned to Cambridge. During Robert’s eleven months in Hollywood at Disney, he did more than basic research. In between interviewing artists and artisans, he constantly wrote and re-wrote drafts of the manuscript, building and shaping it. Fact checking, while he absorbed definitions and critiques, and seeking approvals and guidance from what he described as a “four-ring circus;” meaning Walt and his studio managers and the Whitman and Macmillan publishing teams.It was a steep, often confusing learning curve exacerbated by scant support offered from his Macmillan editor, Arthur James Putnam (1893-1966).60

On December 31, Feild sent the following tense plea to the 47-year old Putnam in New York:

Dear Mr. Putnam:

I am still somewhat at sea over our relationship, and, if this is not exactly an SOS, it is the plaint of one badly in need of cooperation. Before attempting to finish “The Art of Walt Disney” I have decided to revise what I have already done in light of some of the more constructive criticisms I have received, and I hope it is shaping more in accord with what I originally had in mind, and what you may have anticipated. I have cut out the first part considerably, and am in the process of re-organizing the second and third parts to make them run a little more smoothly, but how am I to know whether Messrs. Macmillan will approve the change? Please won’t one of your staff enter into a little closer collaboration and lend me the benefit of their counsel? Now is the time, if ever, for if I am to have the necessary self-confidence to complete the book in the course of the next couple of months it is essential that I feel you approve of what I am doing. Mr. [Georges] Duplaix seems to have ironed things out from the Whitman end, but, after all, it is upon your firm that I must reply for literary criticism and the kind of advice that will knock the book into shape. It is, as you may have gathered, a pretty difficult undertaking, and I am eager to make as good a job of it as I know how. Should it be advisable, I will be glad to come to New York for a conference, but at least let us join forces by correspondence. 61

In addition to goading his editor into action, Feild sent parts of his work-in-progress to trusted friends for advice, among them Frederick R. McCreary (1893-1976), a former colleague in Harvard’s Creative Writing department. McCreary was a published poet who “reached a certain level of fame during his lifetime, with critics comparing him to Robert Frost.”62 He was a close confidant willing to listen and offer sage advice about the work-in-progress and (what Feild called) the “publishing racket.”

More than a note of urgency is detected in Feild’s frustration. This was because he and Helen were hastily preparing to move from Cambridge, Massachusetts to New Orleans, Louisiana. Robert had accepted a full-time position as Professor of Art and Director of the School of Art at Newcomb College, Tulane University, commencing September 1940.

In the early 20th century, Newcomb College, a coordinate women’s college, housed one of the largest collections of the Arts and Crafts style pottery in the American South. Between 1890 and 1940, award-winning bowls, dishes, tiles, figurines, et cetera were made for sale by students and instructors in the Newcomb Art Department. In 1939, Newcomb’s dean recommended the continuation of the “ceramic program only,” insisting that the “emphasis be on the instruction of students and not a commercial enterprise.”63

A search for a head of the revised Newcomb art program led to R. D. Feild, who quickly accepted the offer. Here was a fulltime position of importance in academia, a world he knew well. As opposed to freelance writing, it came with a steady income. Equally important, it was an opportunity to expound to a young audience his progressive art theories regarding “new techniques for the communication of contemporary ideas.”64

Upon moving to Tulane’s campus, Feild immediately distanced himself from the former pottery enterprise and the ceramics classes. He began creating a more diverse program, restructuring the undergraduate curriculum, and embracing the “breaking down wherever possible the artificial barriers . . . between the so-called arts and so-called sciences.”

Many of his ideas, as at Harvard, dealt with teaching photography and filmmaking, “studying the nature of materials, combining the actual experience of the basic dance forms with life drawing.”65

In the mid-1940s, Feild began corresponding with experimental filmmaker, poet, writer and dancer Maya Deren, a leading pioneer of avant-garde cinema. He expressed his being “extremely sympathetic with what you are doing and have much admiration for your abilities and tenacity . . .” At least twice he visited her Greenwich Village studio, while also attending conferences at MoMA in New York; on July 29, 1947, Deren visited his classroom when she stopped over in New Orleans on her way to make a film in Haiti.

As a teacher, Feild continued to be a positive influence on his students. Mignon Faget, one of the most respected jewelry designers in the South, credits Feild’s “Design by Nature” class with inspiring her interest in environmentally-themed design. Overall, Feild’s students were delighted with his diversification of Newcomb’s art curriculum toward experimentation in a creative cross-fertilization of arts forms.

The school’s Board of Administrators was not. Almost immediately, there was pushback to balance Feild’s progressive efforts; in 1942 the Board approved a limited, commercially oriented craft program in the “spirit of original Newcomb Pottery.”

Also, a gimlet eye was cast upon Feild’s support of civil rights activities and academic freedom, which were not favorably looked upon by politically conservative, deep South academe. Eventually, a tense situation developed that would become Harvard redux. 66

The students were delighted; school board administrators were not. Also, Feild’s support of civil rights activities and academic freedom were not looked upon favorably by a politically conservative deep South academe. Eventually, the situation would become Harvard redux. 66

But all that was in the future. Meantime, he had a book to write. “Oh yes. I am still writing the book!” Feild wrote to T. Hee, Disney director/caricaturist, in February 1941 “It may even be published,” he ruefully joked.

. . . it has already passed through many experimental phases, and been subjected to both violent and playful criticism, but somehow it has survived, and it seems at last to be taking shape . . . I haven’t bothered to mention life in New Orleans because I am still too busy with “The Art of Walt” to be conscious of my environment.67

“Things are beginning to move along pretty fast these days,” Feild wrote on March 1 to John Clarke Rose, the Disney Studio Story Research Department manager and editor.

The Disney manuscript is nearly finished, and I have today sent all but the very last part to Macmillan for any further advice and suggestions they may have to offer. I will send the whole thing on to you as soon as it is in final shape.

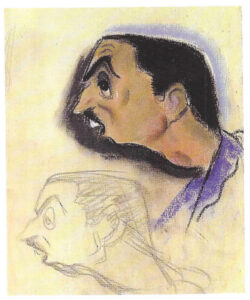

He asked Rose to check on the whereabouts of a promised color caricature of Walt Disney, promised by T. Hee, for the book’s frontispiece. In the final book, a Walt caricature does not appear, perhaps deemed not as dignified as the black and white photograph that replaced it.

Caricatures of Walt Disney by his staff through the years:

“Oddly enough,” Feild wrote in a cheery closing to Rose, “my devotion to the [Disney] Studios [sic] continues, and the urge to return to Hollywood still afflicts me strongly from time to time. Remember me to those who care and be assured of my appreciation for all your help.”68

On April 15, Feild sent Rose a complete manuscript. Rose read it and, true company man that he was, wrote the following non-committal response to Field on May 6:

As I have often said before, the thought of writing a book on this complex operation out here is staggering. Because the book deals with our very life’s blood, it was only natural that I should read it with keen interest. For the same reason I hesitate to offer any editorial criticism whatsoever — living and breathing “Disney” as I do all my life, it is impossible to have a true understanding of Disney’s place in art . . . I am passing the manuscript along to some of the other boys and will send you their comments . . . it might be advisable to wait . . . to review studio staff comments and the publisher’s editorial suggestions before asking Walt to read the manuscript. What do you think?69

Apparently, changes were ordered. It wasn’t until the end of September that unbound preliminary galley proofs were sent to the author for his review. Exasperated, Feild wrote his friend Frederick McCreary on September 23:

Freddie boy: The spot of energy that you used to know as Rob Feild is rapidly disintegrating. He who once endeavored to write a book is now just a drifting mass being flotsamed [sic] about on the shores of time . . . At this crisis in my life, when I am trying to direct Newcomb Art School towards the light, a cloud of galley proof has burst upon me and I am quivering under the shock. It looks lovely, but as yet I haven’t dared to read it. Which is more important, that a book should look pretty or make sense?

. . . Incidentally, Whitman’s did not send any copy to check the proofs with. Isn’t there something wrong about that? And even more incidentally, they tell me that Macmillan’s like to have the book in completed form two months before they release it. Ain’t that queer? Or do you think the public has to be prepared for the “Art of Walt Disney” as gradually as for convoys? Please tell me you are proud of the part you are playing in elevating our cultural standards.70

McCreary said he would review the galleys, but Feild hesitated. On October 3, he wrote:

Fred, the book has now become a nightmare. The galleys came without any copy to check them by . . . All I was supposed to do was to decide if I thought it read all right. Frankly I don’t trust them in this matter . . . Whatever group of circumstances may be responsible, I must confess much of the book reads to me like hell and I once again proceeded to tear it apart.

. . . I am treating the gallies like type-script and altering whole paragraphs freely where the emphasis I intended to make seems entirely to have been lost, or where the mode of expression is what shall I say? Alien to my philosophy? I don’t think any of this is your fault. The cutting on the whole seems to me to be excellent and very frequently the whole sentence structure improved immensely — but at times I suppose my mind just works differently from anybody else’s. If Whitman’s object to resetting the type I’m going to hold them up and refuse to let them publish the book. The worm has at last turned. So help me God, in the end it is going to be my book and nobody else’s – though very much improved in places by Frederick Root McCreery. [sic]

I simply dare not send you the galleys. At any moment now my relationship with Whitman’s may become so strained that one more suggestion or criticism may blow everything apart. Besides, you might want to correct what I have corrected of what you corrected of what they corrected of who corrected what — and the answer would be a mouseling. [sic] So hold your horses, Fred, and if you’re my friend never let me undertake to write a book again. That’s all for now, thank you.71

Feild’s agitated mood was affected by the pressure he was under in heading the Newcomb art school, aggravated by New Orleans’ steamy fall weather. On the first page of his October 3 letter to McCreary (“my gosling friend”) living in the cooler climes of Boston, Feild wrote:

You are finding life in the North complicated? You should try the South. . . something else happens in New Orleans in September. The mind disintegrates or rather it becomes mushy — it sort of gets fouled up into something one might describe as cotton-wool with spots of glue in it, sprinkled freely with sawdust, just phlaaghmmx. (sic) But that’s not all. The furniture begins to fall apart, your clothes rot. your books just disintegrate and your whole physical environment is reduced to a clammy, heartbreaking world of solid sweat.

The Art School flourishes. You know what I mean. It’s just a dank mess with little girls pushing their way through the exotic tangle like pathetic orchids. It isn’t their fault. As always, they’re swell. But God in an idle moment, a very idle moment, and in a perverse mood to boot, made New Orleans, and it’s nobody’s fault if they happen to be born here. You might ask what am I doing here? Ah, Fred, this is heaven to Harvard. We only have to cope with the climate and you have to cope with the evil ways of man. (I think my secretary is getting bewildered by the tenor of this letter.) Frankly I too have lost my way. But even to exert my mind so far has made me sweat through all my attire and has reduced me to an unsavory puddle.72

The date of publication “has varied during the course of the years . . . October 13 and November 21 [1941],” wrote Feild to Macmillan publicist Cynthia Walsh in mid-November. “I am now under the impression that it is expected to be on the market before January.” He also would “be glad if you would give special attention to the spelling of my name. So far in my life I’ve never known it to be spelled accurately twice in succession.” Feild no doubt would have hated autocorrecting Spell-Check.73

BOOK REVIEWS

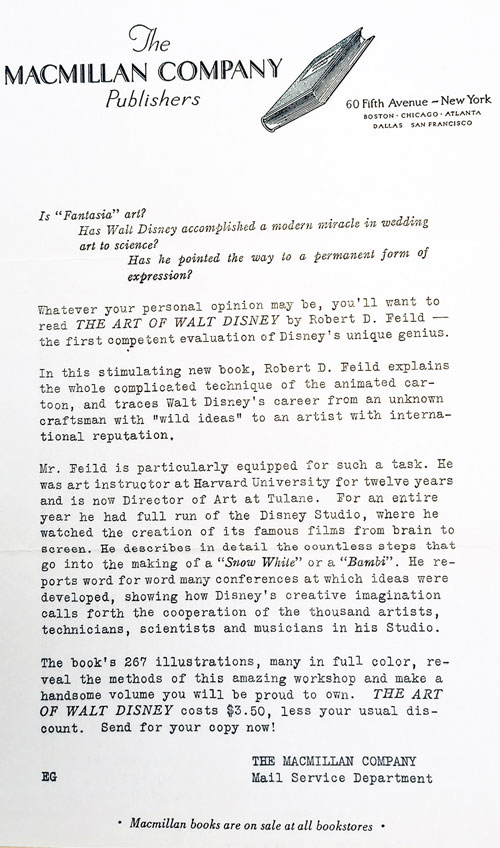

The Art of Walt Disney was finally published in spring 1942, an eight and a half by eleven inches, linen bound hard cover selling for $3.50. The Macmillan Company announced its arrival to potential readers in adverts posing rhetorical questions the book would supposedly answer:

Is “Fantasia” art?

Has Walt Disney accomplished a modern miracle in wedding art to science?

Has he pointed the way to a permanent form of expression?

Whatever your personal opinion may be, you’ll want to read THE ART OF WALT DISNEY by Robert D. Feild – the first competent evaluation of Disney’s unique genius.

For some reviewers, the book’s information proved to be a revelation. “We can never think again that Mickey and his friends merely happened,” observed The New York Times Book Review.

They were planned. They are deliberate. And what a lot of planning, what a number of deliberations, what a factory of ideas and talents they do demand! This is no mere tour of the Disney studios, designed to tell us in easy language how animated cartoons are made . . . it is more. It is a tour of the insides of the heads of the people who make animated cartoons . . . an intellectual attempt to grasp something that the audience isn’t asked or expected to grasp intellectually. . . This is group art, reminding Mr. Feild justly of the workshops of the early Renaissance and the old apprentice system . . . Leonardo might enjoy working in the Disney studios were he alive today.74

The Macmillan Company touted the New York Times “front-page review” of “this illuminating book” in an ad focusing on the studio’s technological processes, promising readers:

You will learn how sound and music are incorporated, how the inking and coloring is done, and finally how the camera-workers get the story on the film strip. All the various complicated processes are simply and clearly explained by the author, who brings you a full realization of the importance of this new art form . . . You sit in conferences and see how a story idea is developed. The direct transcriptions of discussions will delight you, as you listen to Walt and the artists working out those scenes which enchanted you . . . The illustrations show you sketches bringing ideas to life . . .

Jay Leyda, avant-garde filmmaker and historian, wrote enthusiastically in The Saturday Review of Literature:

Feild plunges us into the esthetic and emotional problems peculiar to cartoon-sound-pictures. This is the most brilliant and satisfying analysis that any branch of the modern American film industry has enjoyed at the hands of its countrymen.

. . . The book piles up a structure of indisputable evidence that the Disney Studio is creating an art that we are obliged to understand and appreciate if we have any interest in the development of art in our own times.

. . . The book is a challenge to further investigation of an important art that we all take too much for granted. It is not only Disney who deserves our gratitude for so much entertainment, but Feild as well, for offering such an imaginative recognition of the true nature of this entertainment . . . the abundant pictorial matter furnishes valuable illustrations, inseparable from the text. It has obviously been conceived as a serious book about an essentially visual art. 75

The Film Daily trade paper enthused:

Feild’s work is no stodgy, highbrow tome for the classroom, but rather an extremely readable, deeply intriguing and highly illuminating presentation of . . . ‘the art of Walt Disney as a growing force in our midst.’76

Time magazine offered a cooler assessment, recalling:

Three years ago, Professor Feild stuck his neck out for modern art, Disney’s in particular, and his appointment to Harvard University was ‘not renewed.’ Now he is at Tulane University. Professor Feild contends . . . that Walt Disney has made [animated movies] into ‘the great art form that it is today.’ His book tells the way the medium works, rather than why it is great . . . Professor Feild’s book will not convince standpatters that Disney’s art can compare with that of Ye Olde Tymers. [sic] High-brow pioneers will say, ‘We told you so.’ Fans know already that Disney is in a class by himself.77

Gilbert Seldes, “one of the earliest and most influential writers on the popular arts in America,” and a fervent appreciator of Disney films during the 1930s, wrote a qualified judgement of Feild’s book in the New York Herald Tribune:

This is a big, beautifully made, almost awe-struck tribute to the man whose art has been often called America’s greatest contribution to international friendship and international entertainment as well; not to mention international art.

. . . The information in the book is valuable; but the tone seems to me to be actually promotional; maybe because it is so big, and has so many color plates, it reminds me of elaborate souvenir programs at Aphrodite or the Russian Ballet. The author’s purpose is ‘to present the art of Walt Disney as a growing force in our midst”; actually, he presents the technical devices, the commercial conditions, the physical arrangements; but the art seems to escape.

. . . The animated cartoon is one of the great powers of our time. It has only begun to find its area of operations. Disney’s immeasurable contribution lies in his quick capture of the public fancy and then in his serious effort to push the limitations of his medium further and further with every film. He has made errors; but he has foretold the future of his art.

. . . [the animated cartoon] has not been used as a stimulus to serious emotions; but it is capable of everything. And no one has proved it more than Disney. He needs no promotion; and he deserves more serious understanding than he has received.78

What did Walt Disney think of the final version of the book? His opinion may be deciphered from the self-deprecating letter Feild wrote to Walt on May 12, 1942:

I know the book isn’t all you would have liked it to be. And I shall be the first to confess that it does not do justice to its subject. On the other hand, you of all others are aware, I know, of the innumerable problems that were entailed in amassing the material, writing the text and getting the book through the press.

My great consolation is that no one could have been fired with more enthusiasm for his quest, not retained a deeper admiration for the subject of his work. Where the book falls short it can only be put down to my own inability to rise fully to the heights of the occasion.

In his letter, Feild describes the book as “a souvenir of what I still remember as the happiest and most profitable year of my life.” He explains why he did not communicate with Walt for more than a year while writing the manuscript and grappling with the publishers:

In fact, I have tried to steer clear of all personal relations with the Studio until such a time as my work was brought to completion, lest I become confused over the developments within the Studio [emphasis added] since I left Hollywood.

I have hoped that you would understand my silence and will have taken for granted that nothing which deeply concerns you or the Studio can ever be immaterial to myself. Anyway Walt, here’s the book for what it’s worth and I can only hope that this first effort to appraise your work will not be altogether without value.79

The “developments within the Studio” Feild refers to are dark events that occurred after he completed his research and left in May 1939. Feild’s brief time at the studio was indeed golden — ripe with creative enterprise with seemingly bottomless positive energy emanating from a group effort dedicated to Walt’s continual advancement of the art of animation.

By the time Feild’s book was published, however, the Disney studio was deeply in debt and struggling to survive. Portends of trouble occurred soon after Feild began researching at Disney’s. Hitler’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939 marks the beginning of World War II, which cut off Europe as a substantial income source for Disney films and merchandising.

Then, in 1940, both Pinocchio and Fantasia, two expensive film productions, did not appeal to a wide audience and failed at the box office. Adding more strain on Disney’s finances were high costs incurred in building and staffing the new Burbank studio.

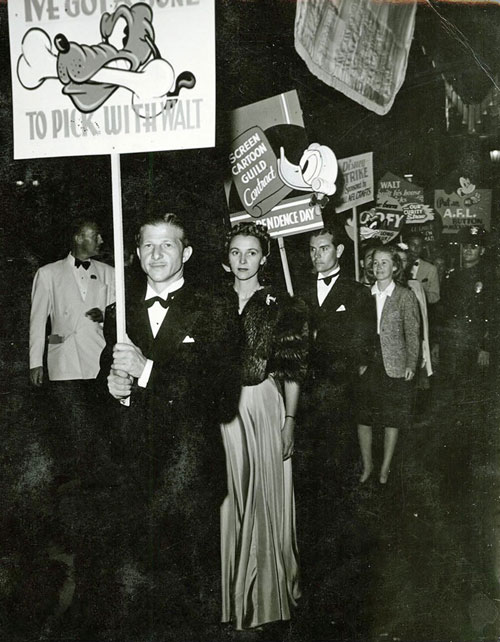

In turn, planned films were curtailed, and promised pay raises and bonuses were denied to employees, who were not protected by a union contract. Layoffs followed domino-style. In May 1941, over 300 discontented, fearful employees, approximately half of the studio’s artists, participated in a bitter nine-week labor strike.

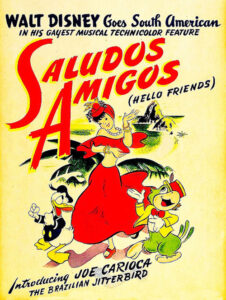

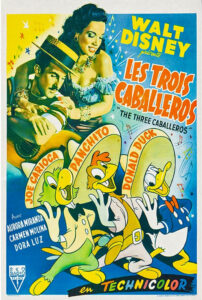

America finally entered the war after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. By that time, the Disney Studio was a union shop with a reduced staff surviving mainly by producing war propaganda and training films, and omnibus features touting US/Latin American “Good Neighbor” policies, SALUDOS AMIGOS (1942) and THE THREE CABALLEROS (1945). 80

Feild’s The Art of Walt Disney book does not discuss, let alone infer, any of those events. It wasn’t meant to. Whether Walt, a perfectionist, liked the final publication or not, the book reflects what he wanted: a deep focus on his studio’s filmmaking art and technical processes, circa 1940.

The book depicts a well-oiled, modern corporation-as- Hollywood-dream-factory under Walt’s leadership and creativity. But unfortunately, it contains no personalizing of the numerous, necessary creative individuals who turned out Disney’s magical films like Geppetto’s toys. Except for Walt and his brother Roy, specific artists are anonymous in the book, identified by only an initial allegedly representing their names.

Some reviewers noticed. Film critic R.L. Duffus, in his admiring New York Times review, wrote:

Twelve hundred people would be lost without [Walt] . . . This is group art . . . This is a factory in which the very machines think . . . the group mind growing from the accretions of individual minds;

a kind of forecast of the future, maybe, after wars are over and men escape from the nightmare of violence and hate into the realities of a gayly imagined world of phantasy.81

Jay Leyda, in his positive assessment of Feild’s book, wrote:

Completed before Pearl Harbor was bombed, the book lacks only one feature that recalls the element of timeliness. How the Disney studio is tackling the urgent new problems of direct propaganda and direct instruction . . . [and] how this complicated organization for expressiveness engages in the art of instruction, would make a useful chapter, even within the esthetic boundaries that Feild has set himself. 82

The “esthetic boundaries” in Feild’s The Art of Walt Disney, were determined by Walt and the publishers. It chose to cast a blind eye on world and local events, primarily the Disney employee strike that profoundly affected the animation industry itself.

“As far as it goes,” Feild wrote in a candid November 19, 1941 letter regarding the book’s content, “it is an honest effort to describe the way things were run in the Disney Studios during the time I was out there.”

Feild’s letter was, in fact, an apologia to his friend, Art Babbitt, master animator and the main firebrand leader of the Disney strike.

Feild continues to Babbitt:

The whole Disney business bewilders me. You are so obviously right and what you have played so prominent a part in getting done had to be done sooner or later. But how terribly unpleasant it must have been and must still be. Had the whole matter come to a head while I was out in Hollywood, I can’t imagine my ever having finished the book. Even now I question very greatly if the book ever should have been written at all – at least in the spirit in which I wrote it. In its present form it is, I hope, a harmless sort of effort and may possibly justify itself in a purely objective way -– but the guts of the whole thing has been left out, since I don’t even touch upon the labor conditions within the studio . . . And even as I look back upon it, I don’t remember any real conflict was impending or even presaged. Perhaps I was all sweet innocence, but even in my talks with you and Bill (Vladimir Tytla, the only other master animator to join Babbitt on the picket line) I never felt the undercurrent of strife that even then must have been brewing. There is a certain naivete about my book which suggests almost an ideal setup – the kind of setup that I think Walt had in mind (if he may be said to have thought about it at all), or perhaps the kind of setup that may develop in the future once he realizes what is meant by Cooperation.