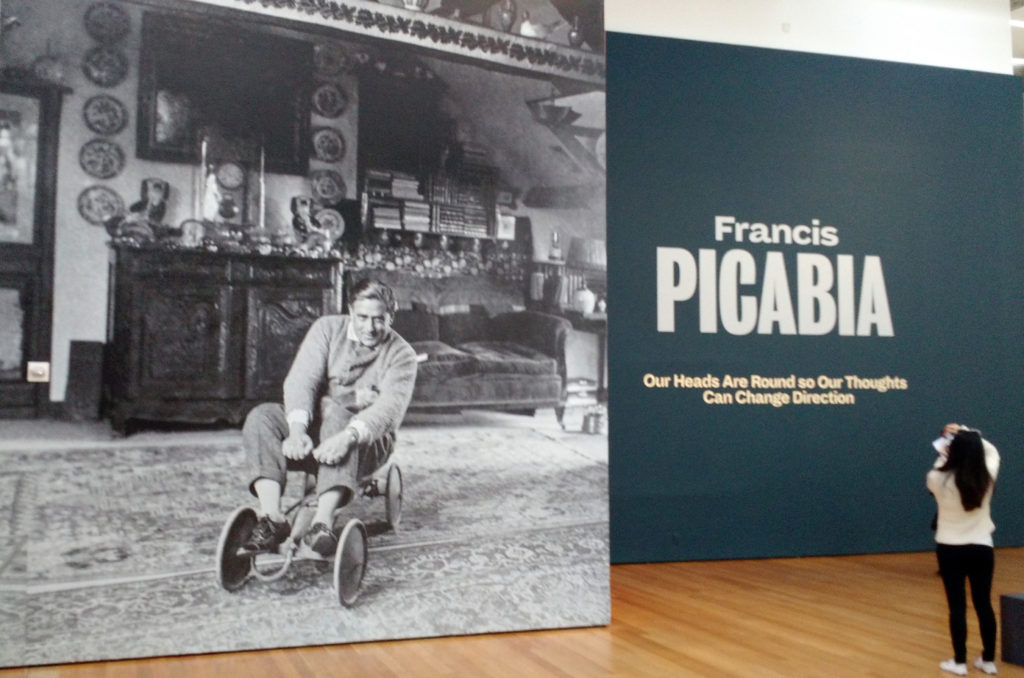

Francis Picabia: Our Heads are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction, now at the MoMA through March 19, is one of the most exhilarating, energetic, and fun exhibitions in town.

Surprise awaits in every room of this comprehensive (over 200 works), elegant survey of Francis Picabia (1879-1953), the elusive French artist who is less well-known than other moderns because of his restless, relentless exploration of a wide diversity of styles, platforms and techniques. “If you want to have clean ideas,” he once wrote, “change them as often as your shirt.”

Impressionism; Pseudo-Classicism; Cubism; Fauvism; Dada; Figuration; Surrealism; Collage; Appropriation; Photo-Realism. Picabia’s been there, done all that.

He was also a poet, publisher, film performer, set designer, and scenarist. Entr’acte, the exuberantly absurd 1924 cinema classic he wrote and appears in (heavy-set man on the right bouncing in slow motion at the beginning), is showcased within the exhibition.

Among the film’s many multiple camera tricks (slow-mo, double exposures) is a tiny bit of stop-motion animation of a cannon. Picabia said the film “respects nothing except the right to roar with laughter.”

Most of his art holds a merry Till Eulenspiegel skepticism, a cynicism that questions what is art and it’s purpose, while manipulating high/low expectations.

In his personal life, he even turned the starving artist trope on its head. Born wealthy, he stayed that way. Befitting his catch-me-if-you-can, shape-shifting personality, he indulged in a love for luxury motorcars, and interchangeable wives and mistresses.

Picabia’s nose-thumbing started, as does this exhibition, with his early Impressionist landscapes inspired not en plein air, but by postcards! One painting caught my animator’s eye with its cartoon-ish organic shapes, unnatural colors, and a mysterious anthropomorphism in the shrubbery.

Picabia’s nose-thumbing started, as does this exhibition, with his early Impressionist landscapes inspired not en plein air, but by postcards! One painting caught my animator’s eye with its cartoon-ish organic shapes, unnatural colors, and a mysterious anthropomorphism in the shrubbery.

I can’t help having an animator’s sensibility, a condition once described by Pixar’s Andrew Stanton thusly: “I can’t remember not thinking that my bike was cold in the rain, that fish are lonely in their bowl, that leaves are frightened of heights as they fall.” (The New Yorker, Oct. 17, 2011.)

In addition to perceiving anthropomorphism, the animation sensibility is seeing potential for motion and emotional expression in static art, in its staging and techniques.

For example, in another early period of the highly-changeable Picabia’s work, we leap with him into a cauldron of giant Cubist canvases roiling with serpentine motion, interlocking sensual shapes, and glowing neon colors.

For example, in another early period of the highly-changeable Picabia’s work, we leap with him into a cauldron of giant Cubist canvases roiling with serpentine motion, interlocking sensual shapes, and glowing neon colors.

In my imagination, they are an abstract, arse-over-teakettle Laocoön.

They contrast with a later blue-hued, contemplative, obviously representational human in the cubist-informed painting, Figure Triste (Sad Visage).

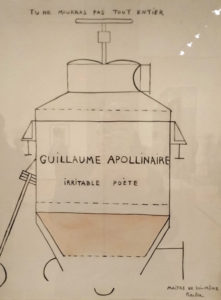

Basic animation principles –caricature, metamorphosis and exaggeration — are in a series of so-called mechanomorph drawings of invented machines.

Picabia’s close friend, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), is the subject of one sketch that manages to be funny and poignant. Apollinaire, a passionate defender of Cubism and Surrealism (terms he originated), is portrayed as a stout container, affectionately labeled “irritable poète.” A second caption, Tu ne mourras pas tout entier (“You will never completely die.”), reveals this drawing to be an obituary portrait of Picabia’s friend.

Picabia’s close friend, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), is the subject of one sketch that manages to be funny and poignant. Apollinaire, a passionate defender of Cubism and Surrealism (terms he originated), is portrayed as a stout container, affectionately labeled “irritable poète.” A second caption, Tu ne mourras pas tout entier (“You will never completely die.”), reveals this drawing to be an obituary portrait of Picabia’s friend.

Picabia’s lifelong love of music is expressed in a joyful, spare abstraction resembling animated, multi-colored musical staffs, titled Music is Like Painting. It triggers thoughts and sounds of a Harry Bertoia kinetic sound sculpture. This, in turn, reminds me of Bertoia’s friendship with abstract animation filmmaker Oskar Fischinger, which began in 1944, a few years after Fischinger’s disastrous experience working at the Disney Studio on Fantasia, to which he contributed numerous concept sketches for the Bach Toccata and Fugue section, ideas that were ignored or abandoned.

Picabia’s lifelong love of music is expressed in a joyful, spare abstraction resembling animated, multi-colored musical staffs, titled Music is Like Painting. It triggers thoughts and sounds of a Harry Bertoia kinetic sound sculpture. This, in turn, reminds me of Bertoia’s friendship with abstract animation filmmaker Oskar Fischinger, which began in 1944, a few years after Fischinger’s disastrous experience working at the Disney Studio on Fantasia, to which he contributed numerous concept sketches for the Bach Toccata and Fugue section, ideas that were ignored or abandoned.

Picabia’s caricatures include a series of so-called Côte d’Azur Monster paintings savaging his fellow 1920s leisure class party revelers.

Picabia’s caricatures include a series of so-called Côte d’Azur Monster paintings savaging his fellow 1920s leisure class party revelers.

There is also the intriguing Transparence series, dreamlike layering of diverse images, seeing through and beyond the obvious, revealing an alternate view, like a camera cross-dissolve, double exposure, or (in traditional hand-drawn animation techniques) a cel overlay that allows a new depth to an image. Here, the angularity and simple lines of Picabia’s overlay image anticipates the spare modernism that would later exemplify UPA’s cartoon aesthetic.

There is also the intriguing Transparence series, dreamlike layering of diverse images, seeing through and beyond the obvious, revealing an alternate view, like a camera cross-dissolve, double exposure, or (in traditional hand-drawn animation techniques) a cel overlay that allows a new depth to an image. Here, the angularity and simple lines of Picabia’s overlay image anticipates the spare modernism that would later exemplify UPA’s cartoon aesthetic.

Greeting visitors to this large, satisfying exhibition is a giant photo blow-up of the artist, riding a tiny cart in an ornate living room. There is a wild-child look on his happy face, challenging you to hop on and join him.

Do it!

You’ll have the ride of your life.

Hits: 2515

Thanks John for this wonderful post. I will share it widely and I hope others will too. It is so easy to miss shows like this when so much is going on in the world! I also love Andrew Stanton’s quote!

John…thanks for that great absurd, time-bending, out-of-control film. Thoroughly enjoyed it.